Tiger Stadium is gone, and no amount of reminiscing, bellyaching, or wishful thinking is going to bring it back. That said, the lingering ardor over the old ballpark is understandable. Between 1912 and 1999, it was a center of crazy tribal passions, a place where the cheering multitudes bonded over walk-off homers, trough urinals, and the embedded reek of grilled franks and ancient cigar smoke. Despite the best efforts of preservationists, the last of the abandoned park was bulldozed into oblivion a few years ago. Today, the vanished landmark is just one more missing tooth in the city’s jawline.

Although Tiger Stadium is irretrievably lost, its fate is hardly unique. Extinct ballparks are sprinkled throughout the Detroit area. While none share Tiger Stadium’s pedigree, each in its time offered the same homey intimacy and on-field thrills, if only for a spell. All but one were subsequently razed and built over, leaving behind scant evidence of their existence. They can be considered “lost” ballparks, but not if you know where to look.

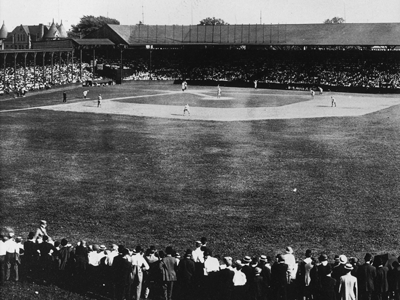

Leading off this informal itinerary of bygone baseball venues is Recreation Park, which was the re-automotive city’s first enclosed ballyard when it opened in May 1879. Built by a syndicate of local movers and shakers, it stood at the intersection of Brush and Brady streets. It was typical of most parks built through the early 1900s. It was constructed entirely of wood and featured a horseshoe-shaped seating configuration. A main roofed grandstand wrapped around home plate, with open bleacher sections running down both foul lines. There were no permanent outfield stands, leaving plenty of room for the occasional overflow crowd and carriages. Harper Hospital stood beyond the left-field fence.

Beginning in 1881, Detroit’s first professional nine, the Wolverines, leased the facility for their National League home schedule. Slugging first baseman Dan Brouthers, the 19th-century version of Miguel Cabrera, and “the people’s choice,” catcher Charlie Bennett, helped Detroit capture the 1887 pennant. The Wolverines went on to whip St. Louis of the rival American Association in a postseason tournament, after which a “World’s Champions” banner proudly flew over the park. However, the club, crippled by a high payroll, folded after the 1888 season. Minor-league ball was played there until the park was razed in 1894. The Detroit Medical Center has since sprung up around the site. Today there is a state historical marker to inform passers-by that, in the general vicinity of Children’s Hospital, mustachioed Gilded Age idols once spent summer afternoons playing ball barehanded and gingerly avoiding horse apples.

In 1891, a young local entrepreneur named Klinger secured a Detroit franchise in the Northwestern League. Riverside Parkwas hastily constructed that May on a parcel of scenic land between Jefferson Avenue and the Detroit River, east of the Belle Isle bridge. Klinger leased the property from the Owen family, which was developing Indian Village directly across Jefferson. One reporter, who dubbed the poorly performing team the “Detroit Weaklings,” observed: “That Riverside Park will be a delightful one in the summer none can deny, but if the men who run around its base lines are not in keeping with the surroundings it will not be very popular.” The club didn’t even make it to summer, folding in early June. In 1893, the deed to the 4-acre parcel was conveyed to the city. Today the site is Owen Park.

In 1894, the newly formed Tigers (then known as the Creams) joined the Western League and rented Boulevard Park for games. The neighborhood park, located at the northeast corner of Helen and Champlain (now East Lafayette) streets, had originally been built as an attraction by a trolley company. The Tigers spent two seasons at the cramped ball yard (the left-field fence running along Helen was only about 250 feet from home plate) before club owner George Vanderbeck, unhappy over the freeloaders who hung like fruit from nearby trees and rooftops, built his own park on the site of a former market at Michigan Avenue and Trumbull Street.

Meanwhile, Boulevard Park soon was leveled to make way for St. Paul’s, which in 1901 was moved from its original downtown location and reassembled, stone by stone, on what was once the Tigers’ diamond. The transplanted Episcopalian cathedral is now known as the Church of the Messiah.

For many years, Detroit’s antiquated “blue laws” forced owners to book lucrative Sunday dates outside city limits. During the 1890s, the Tigers experimented with games in Mount Clemens and Ecorse, prompting raids at both venues, before new club owner Jim Burns built his own diamond on property that his family owned in Springwells Township. Burns Park was located at Waterman Street and Vernor Highway, just on the other side of Detroit’s western boundary. Its small size resulted in an unusually high number of balls batted over the outfield fences or into the stands, to the point that fans who caught them often were forced to give their prize catch back so the game could continue. The smell of the neighboring stockyards hung in the air, but the odor didn’t affect the size or enthusiasm of the crowds. The Tigers played 34 Sunday games at Burns Park (aka West End Park) between 1900 and 1902. Nearly all were marred by rowdyism, as fans (and even some players) got their pre-game drink on at the nearby Garvey Hotel.

A Chicago player remembered once when the visiting team barely made it out alive in their horse-drawn bus. “We won by one run, and as we left the park the crowd came at us with beer bottles. It was the bottom of the bus for everybody, and as I was the most scared I got there first … I was nearly smothered.” It got so bad that the league looked into moving the franchise. It wasn’t until the pennant-winning season of 1907, with baseball-loving politicos now in power, when the Tigers were able to play on the Sabbath. Burns Park continued to host various sporting events through 1916, after which the site was converted to its current industrial use.

The Negro Leagues had a strong presence in Detroit. In 1910, sports promoter John Roesink erected Mack Park at the southeastern corner of Mack Avenue and Fairview Street, just north of Southeastern High. It could seat about 6,000 rooters. The Detroit Stars of the Negro National League, featuring center fielder Norman “Turkey” Stearnes and pitcher Andy “Lefty” Cooper — both future Hall of Famers — were his principal tenant during the 1920s. By the end of the decade, Roesink was also the team owner.

One Sunday in 1929, a fire broke out as park personnel tried drying out the wet field with gasoline. In the panic that followed, 220 spectators were injured, some critically. The press reported one lady whose boyfriend “fought his way back to her, caught her by the hair and dragged her limp body down the grandstand steps.” Another woman “threw her baby from the top row of the stands into the mass of humanity below just as flames swept over her.” Mack Park was rebuilt and continued as a sports venue until the 1960s, when it was torn down and replaced by the Fairview apartments.

The Stars played the balance of the 1929 season at Dequindre Park, which was located at Dequindre and Modern streets, south of McNichols Road. During the 1930s, the park also hosted the Detroit Cubs, a notable black semipro team, as well as various short-lived incarnations of the Detroit Stars, whose name evidently was too good to let go. Dequindre Park was razed after World War II. The main facility of Caramagno’s Foods occupies the site.

In 1930, Roesink spent about $100,000 to build the 8,000-seat Hamtramck Stadium on leased land a block east of Joseph Campau Avenue, near Dan Street. During the 1930s, the Stars and several other black pro teams called it home. Batters cursed the cavernous yard, whose center field was 515 feet deep. Railroad tracks ran behind the 12-foot corrugated-steel outfield fence, an unusual barrier that appears to have been an attempt to deny fans perched on parked boxcars a full view of the action.

The stadium, which Roesink lost to back taxes during the Great Depression and was later renovated by the Works Progress Administration, is one of only a handful of Negro Leagues venues around the country still standing. In 2012, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The shaggy grounds and crumbling grandstand give no indication of an important baseball “first” that occurred here. In June 1930, the Stars became the first Detroit team to play a regulation game under lights when the Kansas City Monarchs brought their portable lighting system to town. By comparison, the Tigers played their first game under the lights in 1948.

The tour ends, naturally, at the northwest corner of Michigan and Trumbull. Amid the sturm und drang of Tiger Stadium’s demolition, it’s easy to forget that the stadium itself was built on the bones of Bennett Park, the Tigers’ history-rich home from 1896 through 1911. The park was named after Charlie Bennett, the popular ex-Wolverines backstop, who a couple of years earlier had been terribly crippled when he slipped while boarding a moving train. Over the course of 16 summers, Bennett Park witnessed Ty Cobb’s debut, three World Series, and a wagonload of other memorable moments. By today’s mega-stadium standards, the park was laughably primeval. It was hammered together at a cost of a few thousand dollars and then expanded in stages, often in slapdash fashion, to keep pace with the Tigers’ success and a growing community. Up until 1900 there still were trees in the outfield. For important games, thousands of fans overflowed the foul lines and outfield, jostling with mounted cops and making an already intimate setting even more snug.

In terms of structural integrity, the facility was little better than a set of Lincoln Logs. “The stands at Bennett Park should be torn down or else some day they will fall in, carrying death to all seated on them,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer warned in 1905. With seemingly every other fan smoking a cigar, cigarette, or pipe, there also was the constant threat of fire. By 1911, owner Frank Navin had bought out the last of the adjacent property owners, allowing him to knock down the wobbly firetrap and build a modern concrete-and-steel structure. There was no outcry and little nostalgia over Bennett Park’s passing. The city that was putting the world on wheels felt it deserved a stadium commensurate with its growing stature.

Navin Field opened on April 20, 1912, the same day Fenway Park did in Boston. The 23,000-seat venue was expanded to become a completely double-decked, 55,000-seat structure and renamed Briggs Stadium in 1938 and Tiger Stadium in 1961. Babe Ruth and Ted Williams considered the place their favorite away park. But unlike Fenway and Chicago’s Wrigley Field (which is celebrating its centennial this season), Detroit’s own classic stadium was abandoned by the team. The move to Comerica Park for the 2000 season ended 104 consecutive seasons at the oldest continuous address in professional sports history. The stadium was razed by the city in 2009. The site is now a fenced lot where volunteers stubbornly chase after windblown fast food wrappers and the ghosts of summers past.

It can be thirsty work exploring a cityscape of lost ballparks. For those who would hoist a glass to their memory, there’s the perfect place right down the street from the Tiger Stadium site. Appropriately enough, it’s called O’Blivions.

|

|

|