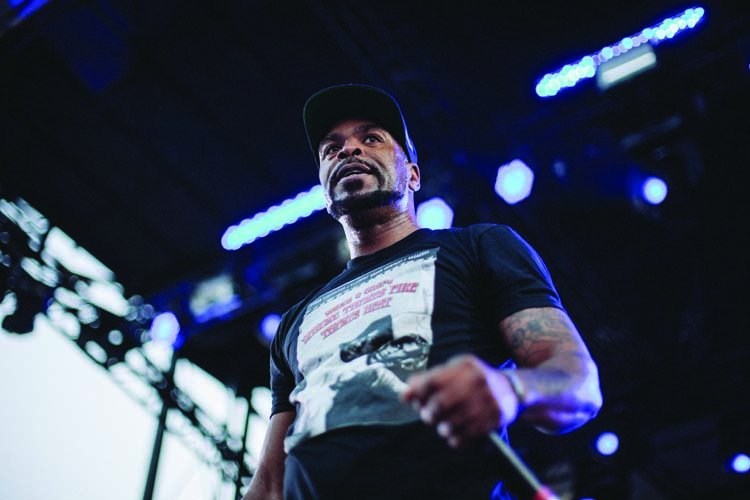

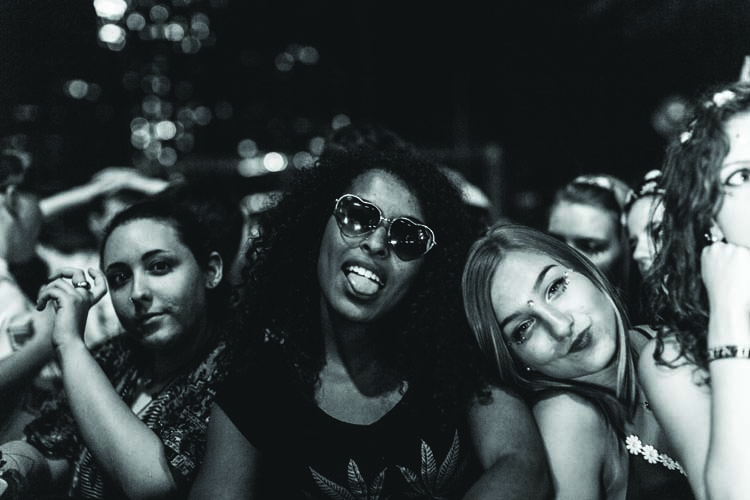

Today, Detroit’s annual Movement electronic music festival is an institution. Last year, more than 111,000 people — many hailing from across the world — packed into Hart Plaza during Memorial Day weekend to see some of the biggest DJs perform in the birthplace of techno music.

It’s hard to imagine the festival, now in its 16th year, of ever having an uncertain future. Yet at various points in its history, the question of whether there would even be a next year was a valid concern.

“Our predecessors were treating it like a part-time job. We knew right away that it was a full-time job,” says Sam Fotias, one of the festival’s organizers. Since 2006, Fotias and business partner Jason Huvaere have run the festival through their event company, Paxahau. “We’ve never had a day off since,” he says with a laugh.

To celebrate, Paxahau (the name, they say, comes from the Mayan language, meaning the “power of music” and “of our time”) is billing this as the 10-year anniversary of the festival.

Of course, the history of Detroit’s Memorial Day electronic music festival goes beyond Paxahau. It first launched as a the Detroit Electronic Music Festival, or DEMF, as a free event in 2000 — back when the genre was still largely an underground phenomenon and the soundtrack of illegal warehouse raves.

Despite the unprecedented nature of the event (and a last-minute approval from the city), the inaugural festival was regarded as a smash hit, bringing a diverse and youthful crowd downtown. However, the following years were marred by questionable finances and backstage drama, which saw the festival change hands several times.

In 2005, the fest debuted as a ticketed event, but still failed to make a profit.

Meanwhile, Huvaere and Fotias cut their teeth throwing their own events, including many after-parties for the nascent electronic music festival. The two say they have been fans of electronic music since the early ’90s, regarded as Detroit techno’s “second wave.” Eventually, they scored a deal to run one of the stages during the 2005 festival.

That’s when they decided to put in their names in the ring to head the next year’s event. It was a high-risk situation for the young company.

“Most of our stuff had been underground dance parties,” says Huvaere. “It was our first time partnering with a public entity like the city of Detroit, and using a public property like Hart Plaza.” The first step in stabilizing the tumultuous festival was to create brand consistency. As management of the festival changed, it went through a variety of names, including “Movement” in 2003. Fotias and Huvaere chose to stick with that name, citing its universal appeal — and distance from what they considered to be a tarnished “DEMF.”

The first step in stabilizing the tumultuous festival was to create brand consistency. As management of the festival changed, it went through a variety of names, including “Movement” in 2003. Fotias and Huvaere chose to stick with that name, citing its universal appeal — and distance from what they considered to be a tarnished “DEMF.”

It’s been the longest-lasting branding for the festival by a long shot. Yet plenty of attendees have still stubbornly referred to the event as “DEMF” — perhaps due to its one-syllable ease, or maybe a sort of hipster “back in my day” type of snobbery, or even possibly genuine ignorance.

The confusion was compounded in 2014, when the organizers of the original DEMF announced they were bringing back the free festival as a Fourth of July event — only to immediately cancel, citing construction of Detroit’s M-1 Rail.

Plenty of disappointed people — some who were even working with Paxahau — mistakenly thought it was Movement that was being canceled. The shakeup caused what Fotias and Huvaere call “two days of confusion,” but now they consider the matter more than clarified: Detroit’s Memorial Day electronic music festival is Movement.

Since Paxahau took the helm, the festival has enjoyed not only stability, but also a higher profile, corresponding with the rise of other “destination festivals” the past decade — think California’s Coachella, Tennessee’s Bonnaroo, or Chicago’s Lollapalooza. Though those other festivals are more pop and rock oriented, the formats are similar, with curated lineups of established and rising musical acts playing across multiple stages.

But in 2006, the festival circuit was still uncharted territory. “When we started producing the event, there were very few electronic music festivals — let alone multi-genre festivals, in the country, or even the world,” Huvaere says.

As it happened, electronic music’s underground heyday in Detroit provided a solid foundation for an event like Movement. “Detroit set itself apart with the rest of what was going on in the Midwest at the time, where the most important aspect of the event was the sound,” Fotias says. “It might have been a run-down building, and maybe there was just one police light or something, but the P.A. just like, belted you in the face.”

That was the scene that provided a petri dish of sorts for Huvaere and Fotias, then teenage fans of electronic music, to throw their own events. “Back then we could get away with stuff that you can’t do now. We were able to set up massive sound systems in unused spaces and go virtually uninterrupted until you were tired, which was the next day,” Huvaere says. “We had a blast.”

In other ways, however, Movement underscores how far electronic music has come from its origins as an underground — and inner city — phenomenon. Today, it’s big business: According to a 2015 International Music Summit report, “EDM” — or electronic dance music, a relatively recent umbrella term coined by the music industry to rebrand the trend — is a $6.9 billion global enterprise, earning some $4.5 billion in festival and club revenue.

In other ways, however, Movement underscores how far electronic music has come from its origins as an underground — and inner city — phenomenon. Today, it’s big business: According to a 2015 International Music Summit report, “EDM” — or electronic dance music, a relatively recent umbrella term coined by the music industry to rebrand the trend — is a $6.9 billion global enterprise, earning some $4.5 billion in festival and club revenue.

This year, Movement’s ticket prices start at $135 for general admission weekend passes and $75 day passes, with $300 “VIP” tickets also available. It’s a far cry from the time it was a free festival.

Huvaere and Fotias say it was inevitable — the first few years of DEMF were sponsored by the city of Detroit, which was relying on grossly inflated attendance estimates to assess the economic impact of the event. Finding a sustainable ticketing model seems to have been the key to the success of the festival. Since taking the helm, Paxahau has grown into a staff of 11 people. In addition to Movement and related after-parties, the company manages production for Jazz Fest and Detroit Restaurant Week, as well as other one-off events throughout the year.

While further details regarding the company’s 10-year anniversary celebration will firm up as Memorial Day draws near, the biggest news so far might be securing German electronic music pioneers Kraftwerk as the headlining act. Huvaere and Fotias say the group has been on their bucket list since they took over the event.

Bringing in Kraftwerk is especially meaningful because of the influence the group had on techno’s roots. (Producer Derrick May once famously described Detroit techno as sounding “like George Clinton and Kraftwerk caught in an elevator, with only a sequencer to keep them company.”) Kraftwerk played at Detroit’s Masonic Temple last October — the first time they had visited the city in nearly a decade. As with the October show, the band’s Movement performance will be enhanced by eye-popping visual effects, with 3-D goggles passed out to everyone in the audience.

The initial Movement lineup also features an ambitious visually enhanced performance by Dubfire. Other acts include Maceo Plex and Amé, as well as Detroit techno veterans CarlCraig, Juan Atkins, Eddie Fowlkes, and Kevin Saunderson. Additionally, Paxahau is planning a “Detroit Techno Week” series leading up to Memorial Day weekend featuring panels and other events.

“There will be an educational component to let people know that electronic music has changed so much in the last 10 years. Ten years ago, it was still a minority in the music business. Now it’s the majority,” Huvaere says. “So we’re going to do our best to get people to understand the impact that this music has had on the music industry and the city of Detroit.”

Asked for insight behind the rise of electronic music, Huvaere shrugs.

“The music’s good. It’s not complicated,” he says. “It’s dance music, for the most part. When people are dancing and they’re in their own head, it’s a more introspective experience. That’s why I think it’s caught on, and why it’s here to stay.”

Movement takes place May 28-30 at Hart Plaza, Detroit. See movement.us for more information.

Memorable Movements

A look back at the ups and downs of Detroit’s electronic music festival

2000: Carol Marvin organizes the first DEMF through her company, Pop Culture Media. Detroit fronts $300,000. Attendance is reported at over 1 million — later revealed to be a gross overestimation.

2001: Ford signs as sponsor, spending $435,000 to name it the “Focus Detroit Electronic Music Festival.” Weeks before the event, Marvin fires artistic director Carl Craig for an alleged breach of contract.

2002: Ford does not renew sponsorship. Marvin replaces Craig with a panel of DJs to book the festival. Critics accuse the bill of lacking Craig’s eclecticism — though the booking of funk icon George Clinton proved to be a hit.

2003: The city of Detroit does not renew funding. Pop Culture’s three-year contract for the event expires. Techno artist Derrick May places a bid to run the festival, renaming it “Movement Detroit Electronic Music Festival.”

2004: The continued lack of city funding puts a strain on the festival, with May putting his own funds into the production — even going as far as driving a golf cart around Hart Plaza, soliciting attendees for donations.

2005: The city approaches producer Kevin Saunderson to run the festival. Renamed “Fuse-In Detroit: Detroit’s Electronic Movement,” it debuts as a ticketed event ($10 day, $25 weekend). Attendance is reported as 41,220. The event still fails to turn a profit.

2006: Saunderson resigns, and Paxahau steps in to run the festival, which they rename “Movement.” Ticket prices are $20 for the day and $40 for the weekend. The lineup features a tribute to J Dilla, who died earlier that year.

2007: Lineup highlights include Rhythm & Sound, Booka Shade, Jeff Mills, Claude VonStroke, and seminal techno duo Model 500. A reported 43,337 guests attend the festival.

2008: The lineup includes high-profile crossover acts like Benny Benassi, Dead- mau5, Girl Talk, and Egyptian Lover. It draws 75,000 — a considerable increase.

2009: Single day tickets start at $30, weekend passes at $60. Highlights include Afrika Bambaataa, Bassnectar, Glitch Mob, Flying Lotus, and RJD2. Attendance is 83,322.

2010: Lineup includes Rhythm & Sound, Radio Slave, a live Plastikman set, Rob Hood, and Theo Parrish. Ford returns as sponsor. Attendance grows again to 95,000 visitors.

2012: Single-day tickets start at $45, weekend passes at $75. For the first year since becoming a ticketed event, atten- dance exceeds 100,000.

2014: Boys Noize, headliners for the festival’s final day, cancels because of illness. J.Phlip steps in as a last-minute replacement, performing one of the most talked-about sets of the year.

2015: Single day tickets start at $65, weekend passes at $110. More than 111,000 people attend the festival.

|

|

|