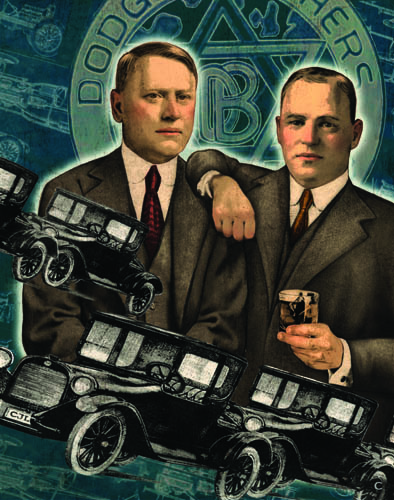

They were inseparable, closer than pages in a book.

Brothers John and Horace Dodge were like the mythological twins Castor and Pollux, whose filial devotion was indissoluble.

And although they weren’t twins — four years separated them — the Dodge brothers made business decisions together, trusted each other implicitly, and loved each other with a Gibraltar-like strength. Those qualities were vital when they started the Dodge Brothers Motor Car Co. a century ago, rolling out their first touring car in 1914 at their massive Hamtramck factory known as Dodge Main.

Even their wives, it has been remarked, were jealous of their brotherly attachment. Sibling rivalry was as foreign to them as speaking Farsi. The hardworking, hard-drinking pair even died within months of each other.

Still, they weren’t mirror images; they possessed different strengths and had different tastes.

“They weren’t cookie-cutter twins,” says Charles K. Hyde, professor emeritus of history at Wayne State University and author of the 2005 book The Dodge Brothers: The Men, the Motor Cars, and the Legacy. “John clearly had the temper that would boil over more quickly. He was more outgoing and was involved in Republican politics. Horace was quiet, more introverted. He also loved music, whereas John couldn’t have given two hoots about it.”

Hyde adds that Horace was more at ease on the shop floor, while his brother was more comfortable handling day-to-day business operations.

But both were highly skilled and industrious mechanics. They were truly self-made men. In building their business, they didn’t have to borrow from banks or rely on currying favor with stockholders. They owned the company outright that bore their names.

The brothers aren’t much remembered today, but their footprints remain large in automotive history, not just for creating their own car, but also for supplying engines and transmissions for Oldsmobile and the Ford Motor Co. In fact, the success of Ford is due in no small measure to the Dodges, who owned 10 percent of that company in stock. When Ford bought them out in 1919 for $25 million, two already rich men became fabulously wealthy.

For years, the monument to the brothers’ mechanical and business ingenuity was the hulking Dodge Main plant in Hamtramck. It was built in 1910 and was enlarged several times as the company grew. Dodge Main, which even had its own test track, was a hive of activity for decades, but was closed by the Chrysler Corp. in 1980 and demolished shortly after.

Keeping the Memory Alive

The brothers’ contributions to automotive heritage aren’t being overlooked in their 100th anniversary year. The Dodge Brothers Club, founded in 1983 and with five regional chapters nationwide, is hosting a Centennial Tour June 22-27 at various metro Detroit locations.

Fans of classic cars may think the Woodward Dream Cruise started early when they see the fleet of vintage Dodges tooling around town. More than 100 vintage Dodges built between 1914 and 1938 are expected to converge on the area, says Dodge Brothers Club President Barry Cogan.

“There is no doubt that this will be the largest gathering of 1914-1938 Dodge Brothers vehicles ever assembled anywhere in the world,” Cogan says, adding that 1938 is the cutoff because that was the last year the words Dodge Brothers and their original logo appeared on the exterior of vehicles.

Automotive history destinations for the visitors include Woodlawn Cemetery, where both Horace and John are interred; Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village; the Edsel and Eleanor Ford house; the Walter P. Chrysler Museum; the Ford Piquette Plant; and a bus trip to Gilmore Car Museum in Hickory Corners. The gathering will culminate June 26 in a free car show open to the public at Meadow Brook Hall, the farm property in Rochester Hills that John Dodge purchased in 1908.

That day will also feature an exhibit of Dodge memorabilia compiled by Meadow Brook Hall, the Dodge Brothers Club, and other sources, in addition to car rides, lectures, entertainment, and other activities, says Kim Zelinski, director of museum operations and advancement at Meadow Brook Hall. She says there will also be private heritage events and meetings June 25 and 27 with members of the Dodge family.

“For us at Meadow Brook Hall, it was just a great opportunity to educate the public about the achievements of the Dodge brothers — and what better way to do that than an anniversary celebration,” she says.

But a one-day celebration hardly does justice to the memory of the Dodge Brothers. That’s why Meadow Brook Hall is planning a permanent Dodge Museum, to be housed in a refurbished sheep barn on the Meadow Brook grounds. It is tentatively set to open at the end of this year, Zelinski says. It will be home to the first model produced by the Dodge brothers, memorabilia, and other items.

Zelinski adds that the fledgling museum will always be on the lookout for items, either offered as a donation or a loan.

“All of these artifacts help to tell the story of the Dodge brothers,” she says. “But it’s more than just about their company; it’s also about the brotherhood of John and Horace. It was a fascinating union and it contributed to their success.”

Henry Ford and the Dodges

When Henry Ford refused to pay dividends to shareholders in order to funnel more cash into the expansion of his company, the Dodges sued, successfully.

There are some observers who contend that the Dodges built their car to compete with Ford and to “stick it” to Ford after their supply contract terminated. But that isn’t quite the case. Ford’s Model T, priced at $490 in 1914, was a budget car; the Dodges’ car, at $785, was in the midlevel bracket. Its closest competitors were Maxwell, Oldsmobile, and Buick.

Henry Ford and the Dodges also remained cordial after the formation of their company. They were never close friends, but neither were they adversaries.

“They had sort of a love-hate relationship,” Cogan says of Ford and the Dodges. “They both did well in business, but they were opposite personalities. They didn’t socialize much together; they were 180 degrees opposite.”

But why, if the Dodges were doing so well supplying parts for Ford, did they sever the relationship? A good deal of it had to do with survival, Hyde says.

“They left Ford for two reasons,” he says. “One was to protect themselves. They knew that Henry Ford was eventually going to become independent and cut them off as a supplier. They didn’t want to have all their eggs in one basket and suddenly have no one to make parts for.

If you’re a supplier in the auto industry, even to this day, you’re in a very vulnerable position,” Hyde says.

“But they also really wanted to make a better quality mid-priced car. They wanted changes made to the Model T almost from the beginning, but Henry was so stubborn that he refused to allow that to happen.”

History shows that Henry Ford indeed wanted to become independent. He expanded his Highland Park plant and built the sprawling Rouge Plant so he could manufacture his own parts.

Ford and the Dodge brothers also had different ideas about employees. Ford lured droves of workers to his company with his $5 day, but he was also suspicious of his laborers. He wanted foreign-born workers to be “Americanized” at night school and favored a rigid workplace climate.

The Dodges couldn’t pay their employees as much as Ford did, but workers enjoyed other benefits well before the United Auto Workers was formed.

Dodge offered employees a free on-site clinic, complimentary life insurance, and other perks.

“Everything I’ve ever read indicates the brothers were very good to their employees,” Cogan says. “At Dodge Main, they had an area they called The Playpen, and after hours employees could come in and use company equipment and tools to work on anything they wanted.”

Factories were sweltering places in those days, devoid of air conditioning. By midday, employees resembled wet dishrags. But the Dodges were compassionate, Zelinski says. “One particularly hot summer the brothers ordered complimentary sandwiches and beer that were brought in to employees every day during July and August,” she says. “They may have used unusual means, but they were very well liked by their workers.”

Revving Up the First Dodge

Many car companies emerged on the scene in the early 20th century, but most lasted only a few years or merged with other firms, Hyde says.

“I used to tell my students that in 1914, there were something like 45 or 50 automotive brands that were launched. But there’s only one that has survived today, and that’s Dodge.”

So what made the Dodge car so different, so superior, that it outlasted so many competitors?

In a word, quality. For one thing, the Dodge had an all-steel body.

“The typical practice of that era was that there would be a wood frame and then they’d attach a skin of sheet metal on to that wood frame,” Cogan says.

“Dodge was different from the very beginning. Their bodies were all steel, made by the Budd Co. in Philadelphia. The only wood was in the floorboards.”

“They really developed the new car from scratch,” Hyde says. “They made it very clear that it was going to be different from the Model T, more advanced, with a bigger engine.”

The public — and the press — noticed. The Dodge developed a reputation as a solidly built, reliable auto. In 1915, a sporty roadster was offered, along with the touring car. By 1920, there were five Dodge models.

Their advertising was effective, too. According to Hyde’s book, the Dodge Brothers Motor Car Co.’s 1916 ad campaign slogan was short but punchy: “It Speaks for Itself.”

Mechanics in the Making

Mechanics in the Making

The Dodge brothers were born in Niles in the southwest corner of the state — John in 1864 and Horace in 1868. They also had an older sister, Della.

Their father and his brothers ran a machine shop, and the Dodge boys soaked up all they could about machinery. When they were teenagers, the family hop-scotched across the state, first to Battle Creek, then Port Huron, and finally, in 1887, to Detroit.

In Port Huron, John and Horace honed their skills at Upton Manufacturing Co., which made agricultural equipment.

When the family settled in Detroit, the brothers found work as machinists at the Murphy Iron Works. Several years later they were employed at the Dominion (later Canadian) Typograph Co. in Windsor. While in Canada the brothers teamed up with Fred Evans and created the Evans & Dodge Bicycle Co.

By 1900, the siblings had accrued a boatload of experience and were ready to strike out on their own. They opened a machine shop in the Boydell Building on Beaubien Street, which still stands today; the ground floor is home to Niki’s Pizza. The company, simply called Dodge Brothers, quickly established a reputation for top-quality work.

In 1901, Ransom E. Olds, the head of Olds Motor Works, hired Dodge Brothers to build engines for his autos. Soon after, they were hired to build transmissions. It was a boon to their business, but another contract would catapult the Dodge brothers into automotive history and make them wealthy men.

In 1903, Henry Ford approached the brothers to make parts for his young company. They agreed, and business boomed, so much so that the brothers had to build a larger factory on Monroe Avenue. When they outgrew that, they built another factory — Dodge Main.

Boozing & Brawling

Boozing & Brawling

Horace and John were redheads with stereotypical fiery tempers to match. They also had a penchant for getting loaded and engaging in fisticuffs. The most notorious example took place in 1911 at a downtown bar where John and a friend were carousing. No one knows what ignited the fight, but John and his buddy set upon an attorney who had two wooden legs and gave him a sound beating. The man tried to defend himself with a cane, but the two men proceeded to kick him like a donkey. Predictably, the lawyer sued the pair; the case was settled out of court.

Another time, after a Dodge sales convention, John and his pals repaired to a downtown saloon. At John’s command and under the threat of a revolver, the bartender was forced to dance atop the bar. Then the plotzed John proceeded to go on a glass-smashing spree, racking up thousands of dollars worth of damages.

John’s short fuse wasn’t always set off by booze, however. Bristling about a critical story about him and his colleagues in the Detroit Times, John headed for the home of James Schermerhorn, the paper’s publisher. When the hapless man answered the door, the barrel-chested John belted him a couple of times and promised a more thorough thrashing if the paper persisted in its calumny.

But Horace was no shrinking violet. Once, outside a downtown saloon, he couldn’t get his car started and futilely went about cranking the engine. A passer-by poked fun at his mishap, and an outraged Horace nearly sent the man flying into the next galaxy.

Such outbursts were reported in the press and “genteel society” looked askance at such public meltdowns. Officials at Detroit’s prim University Liggett School (now in Grosse Pointe Woods), where John’s daughters attended, threatened that the girls would be expelled if their father’s soused exploits continued.

Their wild behavior barred the brothers entry to some of the city’s most exclusive clubs. Horace’s application to the Grosse Pointe Country Club was rejected, and both brothers were denied membership at the Detroit Club, although it eventually accepted them. However, the Detroit Athletic Club gave them membership, and the brothers threw lavish sales parties there.

It would be a mistake, though, to view the brothers as a pair of hooch-guzzling yahoos who were constantly hammered. They simply couldn’t have accomplished what they did and run a company efficiently if they had been plowed most of the time.

“They were like certain college students today; they were binge drinkers,” Hyde says. “They drank and got into trouble maybe one night a month, but the rest of the time they worked.

“Despite their reputations, they really were workaholics,” he adds. “They may have been alcoholics, too, but their life was the business.”

Cogan agrees. “I think when they got off work and let go, they really let go,” he says. “Binge drinking is probably a good description, because they were hard workers.”

Despite their bad tempers, the Dodge brothers had kind hearts. They were generous to the Salvation Army and other organizations.

Horace donated at least $100,000 to the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and both gave great sums to the Presbyterian Church. But their largesse wasn’t often reported.

“People didn’t know about a lot of their philanthropy,” Zelinski says. “Sometimes they’d support a poor guy at the factory who could no longer work, a favorite waiter whose widow fell on hard times, or kept people on the payroll and provided a pension for them.”

Family Life

Family Life

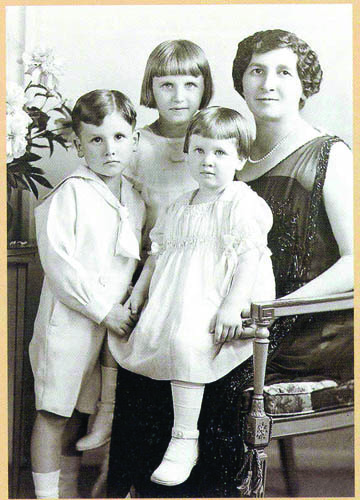

Being the older brother, John was unsurprisingly the first to marry. He wed Ivy Hawkins in 1892, and they had three children: Winifred, Isabel, and John Duval. Ivy died of tuberculosis in 1901. John’s marriage to Matilda Rausch in 1907 produced three more children: Frances, Daniel (Danny), and Anna Margaret.

But what’s interesting is that John kept secret a second marriage, to Isabelle Smith. They wed quietly in Canada, but the nuptials didn’t last long, and there didn’t appear to be much romantic fire between the two.

“John always referred to his second wife as his housekeeper,” Hyde says.

Caroline Latham and David Agresta’s often catty book, Dodge Dynasty: The Car and the Family That Rocked Detroit, published in 1989, maintains John “treated the poor woman abominably.”

It wasn’t just his furtive second marriage that raised eyebrows. In 1982, a woman named Frances “Pat” Mealbach claimed she was the Siamese twin of John’s daughter Frances, born in 1914. Siamese twins are identical. They not only resemble each other, but also show very similar personality traits. “I didn’t believe the story from the beginning,” Hyde says. “I think that woman could have been the illegitimate child of John Duval Dodge, thus the family resemblance. She may have been born to one of the maids John Duval had sex with.”

Horace’s relationships held much less intrigue. He married only once, to Anna Thomson, in 1896. They had two children: first Delphine, then Horace Jr.

Anna and Matilda came from humble circumstances. Matilda was the daughter of a saloon owner and worked as a Dodge secretary. Anna taught piano privately and worked in a bakery.

Once they reached adulthood, their scandal-plagued children appeared frequently in newspapers in Detroit, Palm Beach, Fla., New York, and elsewhere.

None of the children appeared to be interested in contributing to the family business. All were intent on enjoying, and sometimes squandering, their inheritance. The high life was theirs to embrace: Frances and Isabel were mad about horse racing; John Duval loved speed — autos, boats, and fast women; Horace had a passion for boat racing (and wives); Delphine loved yachting. The family penchant for alcohol also led to the destruction, even the demise, of some children.

There was a Kennedy-esque pall of tragedy that seemed to hover over the family. In 1942, after a night of heavy drinking and possible philandering, a combative John Duval Dodge died after slipping into a coma following a fall at a Detroit police station. There’s always been the suspicion that police brutality, not a fall, led to John’s death. His half-brother, Danny, died mysteriously four years earlier on Canada’s Manitoulin Island after being injured throwing dynamite. He went overboard while being transported by boat to the hospital. His body was found three weeks later. The boys didn’t seem to have their fathers’ talent for mechanics, but Danny appeared to be an exception, tinkering in his workshop at Meadow Brook Hall. He was 21 when he died.

Matilda’s youngest child, Anna Margaret, suddenly took ill and died at 5 years old.

Horace Jr., a boat-racing enthusiast, constantly made the society and gossip pages, if not for yet another marriage (he had five), then for his booze-fueled antics. In the 1950s, the gossipy Confidential magazine headlined an article: “Meet Horace Jr., the Only Dodge That Ever Ran on Bourbon.” In 1963, the toll of heavy drinking, together with a bad heart, did Horace Jr. in.

Horace Jr.’s sister, Delphine, was a pretty party girl who loved riding aboard the 258-foot yacht named after her. After three marriages and a life in the fast lane, she died at the age of 43. According to Latham and Agresta’s book, she died of “the physical ravages of acute alcoholism.”

The Death of the Brothers

Because they were so close in life, it perhaps seems fitting that the Dodge brothers died within a year of each other. On a trip to New York’s National Automobile Show in January 1920, John contracted pneumonia and died. His lungs had been compromised by a battle with tuberculosis years earlier.

Horace, already in poor health, was inconsolable after the loss of his brother and died in Florida in December 1920.

“His drinking got worse,” Hyde says. “I think I was the first person to locate his death certificate from the State of Florida, and it states very clearly that he died of complications from cirrhosis of the liver.”

In 1925, the brothers’ widows decided to sell the company to Dillon, Read & Co., a New York investment banking firm. The price was a whopping $146 million, at the time considered the largest cash transaction in history. Three years later, Walter Chrysler bought the company.

After the sale, Anna and Matilda were rolling in dough. Matilda married lumber magnate Alfred Wilson in 1925. Matilda and John lived in a large Tudor home on Boston Boulevard, built in 1906. Just before John died, they planned to move to Grosse Pointe, where they were building a sprawling mansion. It was never finished and was demolished in 1940. Perhaps the memories with John were too sad for Matilda to complete the house. However, many materials were salvaged and transplanted to Matilda’s new residence, Meadow Brook Hall, erected in 1929. That Tudor mansion survives as a tourist destination. Matilda, who died in 1967, left her property to Michigan State University-Oakland, which later became Oakland University.

Anna wed actor Hugh Dillman in 1926 and divorced him in 1947. In the early ’30s, she tore down the original sandstone Rose Terrace in Grosse Pointe Farms where she and Horace lived and built on the same site a magnificent Louis XVI mansion teeming with paintings and 18th-century French antiques.

The contents of Anna’s beloved music room were donated to the Detroit Institute of Arts. She also owned a Palm Beach estate, called Playa Riente (“Smiling Beach”). The second Rose Terrace was razed in 1976, six years after her death. Anna was just shy of her 99th birthday.

Today, the Dodge descendants live quietly; their names seldom appear in the media, at least not disparagingly.

John and Horace, so close in life, rest together in eternity at a mausoleum flanked by two sphinxes, in Detroit’s Woodlawn Cemetery. The sphinx, an Egyptian mythological creature that’s part human and part lion, is much like the rambunctious redhead brothers — inscrutable and stock-still, but ready to roar and pounce at the slightest provocation.

|

|

|