Any discussion of “The Twist,” one of the seminal songs in pop music history, threatens to throw an old rhythm-and-blues fan like Doc Lawrence slightly out of joint. “It will always be Hank Ballard’s song,” insists Lawrence, who over the years saw the Detroit-born artist perform more times than he can remember. “Everybody else just stole it from him. Especially Chubby Checker.”

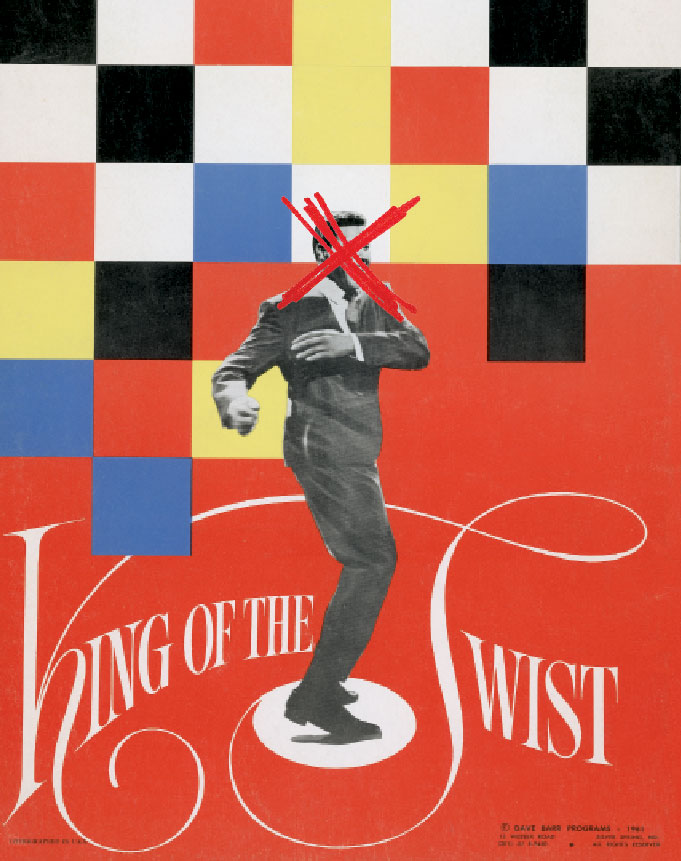

To the masses, the zigzagging and perpetually beaming Chubby Checker is synonymous with the Twist, both the song and the worldwide dance craze it inspired. His chord-for-chord cover of Hank Ballard and the Midnighters’ 1959 B-side single is still the only record of the rock ‘n’ roll era to top the charts on two separate occasions: first in 1960, then again in 1962. A generation later, Chubby’s collaboration with the Fat Boys on “The Twist (Yo, Twist!)” demonstrated the song’s remarkable durability. In 2008, Billboard magazine named “The Twist” the biggest hit in the history of its Hot 100 charts. Given such extraordinary success, the man promoted as “The High Priest of the Twist” understandably feels very proprietary about the song — which may be why Checker’s camp ignored an interview request for this story. Like the pointy-toed shoes Checker screwed into the floor in those low-budget “Twist-errific!” dance movies of the early ’60s, any reminder of the debt he owes Ballard probably rubs a sore spot.

It doesn’t help matters that Ballard was an early inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, joined last year by the Midnighters (who were elected as a group), while Chubby continues to wonder who he cheesed off on the selection committee. “If it wasn’t for Hank Ballard, I wouldn’t be here,” he conceded in a 2010 interview in Keep Rockin’ magazine. “But listen, you know, people always talk about Hank Ballard … It seems like people are angry at me because I recorded ‘The Twist.’ ” Actually, the snub is not that surprising, says local music writer Susan Whitall. “Hank is seen, rightly so, as an R&B legend who wrote most of his own material, while Chubby was a manager-created phenomenon.”

Ballard was born John Henry Kendricks in Detroit on Nov. 18, 1927, though as a performer, he routinely shaved nine years off his age by claiming a 1936 birth date. His father, a truck driver, died when Ballard was 7. Ballard moved to Alabama to live with relatives, but returned as a teenager, having soaked up such disparate influences as church gospel music and Gene Autry, the singing cowboy. In 1953, Ballard was working on the Ford assembly line when he was invited to join a local doo-wop group, the Royals. “I had them change to a more driving, up-tempo thing,” Ballard later recalled. “You know, let’s get funky!”

Ballard wrote and sang lead on the Royals’ breakout hit, “Work With Me, Annie.” The lyrics (“Annie, please don’t cheat/Give me all my meat/Oooo-weee”) were raunchy enough to cause the FCC to ban the song from the airwaves. Nonetheless, it was a jukebox favorite and the top-rated R&B song of 1954. In order to avoid confusion with another group, the Five Royales, the Royals renamed themselves “the Midnighters.” In the studio, the ensemble recorded a string of blues-based hits with infectious gospel-style harmonies, while on stage they cranked up crowds with their full-bore, joyously risque song-and-dance performances. In all, the Royals/Midnighters would place 20 songs on the pop or R&B charts.

“The Twist” was first recorded as a demo in Miami in early 1958, remembers Norman Thrasher, a still-active Detroit vocalist who joined the Midnighters that year. “Cal Green, our guitarist, worked with Hank on it,” he says, though Ballard claimed sole ownership of its composition. On Nov. 11, 1958, a polished master was recorded at King Records’ Cincinnati studios. Ballard thought it had hit potential, but instead it was released as the “B” side to the Midnighters’ “Teardrops on Your Letter.” The dance slowly caught on when the Midnighters took their act on the road, though Thrasher grew exasperated by the group’s total disdain for rehearsal of any kind. “We’re not twisting,” he told them at one point. “We’re wiggling.” Whatever one called it, by 1960, teenagers in Baltimore were swiveling to the rhythm on a local TV dance show. Its popularity drew the attention of Dick Clark, the producer and host of Philadelphia-based American Bandstand.

Clark’s baby-faced wholesomeness masked a savvy and occasionally unethical business sense. He recognized the Twist’s huge potential and wanted to release the song on Parkway Records, a label co-owned by his wife. Clark worked out a deal with Sid Nathan, the cigar-chomping president of King Records, who never liked “The Twist.” In exchange for granting Parkway the rights to record its version, Nathan got a cut of the profits and Clark’s promise to showcase other Midnighters songs on his nationally broadcast show. These turned out to be “Finger Poppin’ Time” and “Let’s Go, Let’s Go, Let’s Go,” a couple of hip-shakers whose sales benefited greatly from their exposure on American Bandstand.

Clark never considered having the streetwise Ballard as the face of the Twist. He was 32, had dark skin and processed hair, smoked dope, and had a name that, in R&B circles, was synonymous with censorship. No, Hank Ballard was not the right kind of black man to be invited into America’s living rooms week after week. However, a sunshiny, light-skinned 18-year-old named Ernest “Chubby” Evans was. Evans, a South Carolina transplant who worked at a local poultry shop, had already recorded a couple of singles with Parkway. One was a mildly successful parody in which Evans mimicked the voices of various singers. He sounded almost exactly like Ballard. Clark’s wife, playing off the name of crossover R&B artist Fats Domino, suggested Evans call himself Chubby Checker. In the late summer of 1960, the Midnighters’ reissued version of “The Twist” was moving steadily up the charts when Chubby’s version, heavily promoted on American Bandstand, shot past it, on its way to earning a gold record as a certified million-seller. “Man, when we first heard it, we all thought we were listening to our own song,” Thrasher recalls. “Chubby copied it, note for note.” Checker not only appropriated the Midnighters’ sound, Thrasher says, he took their dance moves. “He came up to us at the Uptown Theater in Philadelphia, this was in 1961, and asked us to help him out.” Everybody ignored him except for Thrasher, who soon had Chubby’s choreography looking correct.

In the late summer of 1960, the Midnighters’ reissued version of “The Twist” was moving steadily up the charts when Chubby’s version, heavily promoted on American Bandstand, shot past it, on its way to earning a gold record as a certified million-seller. “Man, when we first heard it, we all thought we were listening to our own song,” Thrasher recalls. “Chubby copied it, note for note.” Checker not only appropriated the Midnighters’ sound, Thrasher says, he took their dance moves. “He came up to us at the Uptown Theater in Philadelphia, this was in 1961, and asked us to help him out.” Everybody ignored him except for Thrasher, who soon had Chubby’s choreography looking correct.

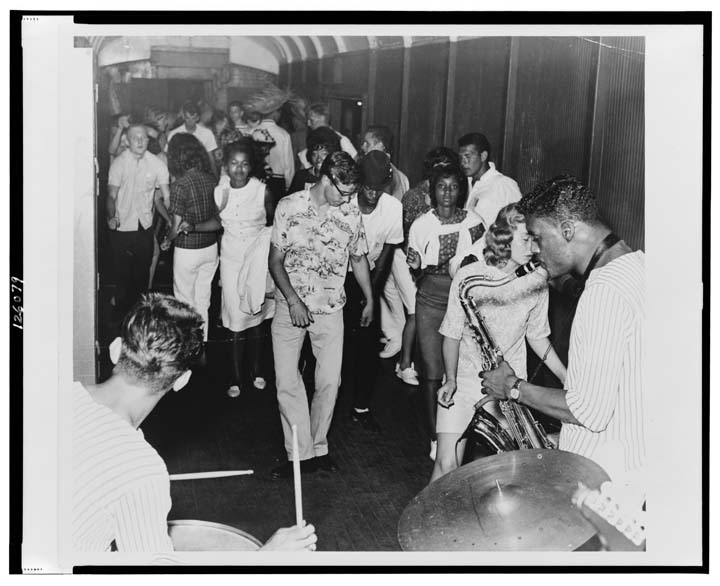

It’s hard to overstate the Twist’s impact on the music industry and on pop culture. Priests, PTA boards, police officials, and stodgy dance instructors were predictably outraged. One self-appointed guardian of public morality, James I. Flanigan, declared the dance was “of evil origin” and was “used by Satan in inducing thousands of teenagers in a type of hypnotic ecstasy.” Few paid attention. Doing the Twist was fun. Even highbrow dance master Arthur Murray came on board, his chain of studios offering flat-footed fuddy-duddies “six easy lessons” for $25. For the first time ever, moms and dads joined the kids on the dance floor, all grinding away like the agitator in the family washing machine.

And they had plenty to dance to, as record companies scrambled to capitalize on “Twistmania.” The outpouring included Sam Cooke’s “Twistin’ the Night Away,” Joey Dee and the Starliters’ “Peppermint Twist,” and the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout” (later a hit for the Beatles). Berry Gordy released Twistin’ the World Around, a forgettable album by the Twistin’ Kings (actually the house band later known as the Funk Brothers). Gordy also rushed the Marvelettes into the studio to record “Twistin’ Postman,” the follow-up to the teenage group’s “Please Mr. Postman,” Motown’s first No. 1 pop single. “Twistin’ Postman” was one of 20 Twist singles to make Billboard’s Top 40 between 1960 and 1962.

Nobody cashed in like Checker, whose output featured the Grammy-winning “Let’s Twist Again,” and several novelty dance songs: “The Fly,” “The Hucklebuck,” “Pony Time,” and “Limbo Rock.” At one time, he had six of the country’s 10 top-selling albums, something no other recording artist has ever done. In January 1962, 17 months after his version of “The Twist” had reached No. 1 on the pop charts, a reissue again reached the top spot. Chubby was rich, famous, and ubiquitous. To top it all off, the one-time chicken-plucker from the projects of Philadelphia dated (and later married) Miss World of 1962.

In November 1961, about the time Motown’s Twist platters dropped, Ballard appeared on To Tell the Truth. As he and two impostors were introduced to the game show’s audience, the voiceover declared, “I am the composer, author, and originator of ‘The Twist.’” Sleek, dapper, and effortlessly cool, softly moving his hips and lips as the panelists fired questions,

Ballard stood out from the bland pretenders. However, when asked to choose between him, an erudite psychologist, and a bulky offensive end for the New York Giants, only one of the four panelists could correctly identify “the real Hank Ballard.” The performer left with $750, a carton of Salems, and a reaffirmation that, when it came to the song and dance that were sweeping the planet, there was Chubby Checker, and then there was everybody else.

Not that anybody was complaining, Thrasher says. “It didn’t take anything from us. We were working every night, and Hank was cashing those songwriting checks, so nobody cared.” The Midnighters were playing 300 gigs a year, including a booking at Florida State University. Doc Lawrence was part of the student committee that convinced school officials to invite Ballard to campus. “They asked me, ‘Do you think he’s appropriate for homecoming?’” Lawrence, now a producer in Atlanta, recalls. “I said, ‘Oh yeah, he’s a perfect choice.’ Hank came in and put on the most stimulating, daring, raunchy performance. ‘Work with Me, Annie,’ all those great songs. Flawless. Nobody was in his league.”

Ballard — who, like most artists of his era, justifiably complained of being exploited by agents, producers, and publishers — was not above taking advantage of others himself. He didn’t share writing credits on “The Twist” and other songs, and as the group’s front man, he became more demanding. “Hank wanted all the money,” Thrasher says. After 1963, Ballard and the Midnighters went their separate ways, “and Hank never did have another hit record after that.”

Ballard blamed the breakup on several members becoming Black Muslims and refusing to perform before white audiences. “It was tough on me because they were the act; they’re the ones that did everything on stage,” he said years later. “Me, I just sang.” Ballard eventually gained legal rights to the group’s name and toured with a new set of Midnighters. But like most acts of his era, the musical revolution of the ’60s turned him into an anachronism. He had a short-lived fling on soul singer James Brown’s label and resisted the oldies circuit for as long as he could. A self-described drifter, he moved around the country, with stops in Nashville and New York.

In 1975, desperate for cash, Ballard sold his composing rights to “The Twist” for a mere $5,000, but he later regained them, thanks to a favorable untangling of the song’s copyrights. “I made a lot of money on that song,” he told music writer Bruce Pollock in 1979, by which time he was living in a small Miami apartment with his second wife. “Of course, it was just a drop in the bucket to what Chubby made.” Ballard, whose Cadillac vanity plate read “TWSTER,” always maintained that he bore no animosity toward the man who overshadowed him, though he once had his lawyers challenge Checker’s claim in a TV spot that he was the “creator of the Twist.” The commercial was for Oreo cookies, an irony apparently lost on the ad agency that hired Chubby.

Ballard was already enjoying a renaissance of recognition when he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990. He recorded in England and contributed to soundtracks, but within a few years, his distinctive, driving voice was stilled by throat cancer. He died in Los Angeles in 2003.

Checker, now 71, continues to profitably churn his geriatric hips at nightclubs and private parties. Norman Thrasher was recently in New Orleans at a benefit for Fats Domino. Chubby was there, and so was Little Richard, who called the old Midnighter up on stage. Thrasher, approaching 80, responded by giving the crowd a taste of the Twist. “Oh, yeah,” he says. “You’re never too old to twist.”

|

|

|