At downtown Detroit’s Richter’s Café on State Street, a single empty bottle hung suspended upside-down from a swathe of black crepe. Pinned to the bottle was a bedraggled bouquet of faded asters dimly lit by a red lantern. The doors were locked, the windows shuttered, and the lights extinguished inside.

King Alcohol was dead.

Michigan’s May 1, 1918 enactment of Prohibition made Detroit the first major city to abolish alcohol. The factors leading up to the law had as much to do with political and economic machinations as with moral and social influences. With booming population and manufacturing growth, Detroit drove full-force into the 20th century, but in many ways, it was still a provincial town in its mindset.

When asked how Detroit went dry, Michigan Anti-Saloon League superintendent Grant M. Hudson crowed: “The Prohibition of today is … the war cry of all classes, all industries, of all professions.”

Some Michigan residents had been trying to end drinking since the territory achieved statehood in 1837. An early constitution placed strict regulations on liquor sales. In 1845, Michigan became the first state to introduce a “local option” in which each municipality could decide for itself whether to go dry. This “Home Rule” was in direct opposition to groups rallying for statewide Prohibition. The Washingtonian Society and the Anti-Saloon League held massive rallies and lobbied hard at the local and federal level for temperance.

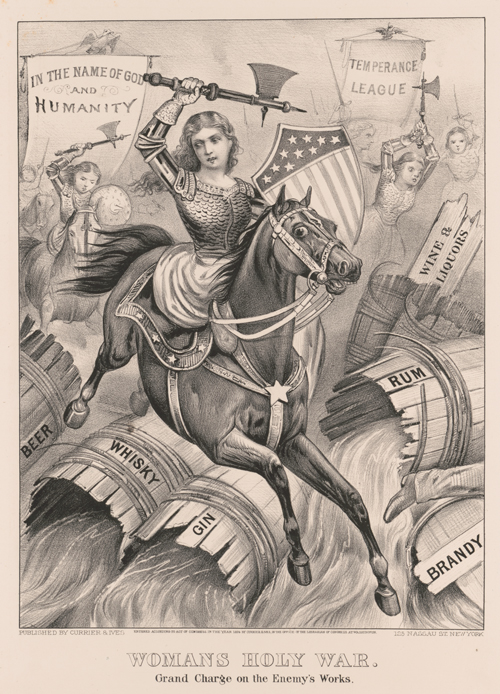

Against the Demon Alcohol

Drinking in 19th century Michigan was rampant and destructive. Before Detroit went dry, more than 6,000 saloons, mostly unregulated, sold beer, whiskey, and moonshine. Alcoholism was at epidemic levels, and stories proliferated of men who took their paychecks straight to the saloon and drank them away in an afternoon. Billy Boushaw’s Bucket of Blood dive on Atwater was infamous for getting patrons drunk on election day and marching them from precinct to precinct to vote a dozen times.

Although alcohol was prohibited, an initial loophole allowed private in-home consumption of items already possessed before May 1, 1918.

Domestic abuse rates were five times their current levels. It’s no wonder the largest group of Prohibition advocates in Michigan was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Campaigning for temperance and suffrage together, its members marched in white dresses and staged mourning ceremonies outside of saloons. They held candlelight vigils and lined up in thousands in an effort to shame men away from the doors. The WCTU threw its weight behind the Anti-Saloon League, and in 1899 Susan B. Anthony declared, “The only hope of the Anti-Saloon League’s success lies in putting the ballot into the hands of women.”

Prohibition and suffrage went hand-in-hand. Given the right to vote, many believed, women’s first act would be to banish the evils of the saloon. Popular novelist Jack London’s 1913 memoir John Barleycorn predicted that it would be “the wives, sisters, and mothers and they only, who will drive the nails into the coffin of John Barleycorn.”

To convince Detroiters, though, some more showmanship was needed. While the rest of the state, mostly rural, was nearly half dry by 1911, it took some bombast and pageantry to win over hard-drinking Detroit residents.

Enter Carrie Nation and her “Hatchetation Nation.” The WCTU grudgingly supported Nation’s tempestuous 1908 Michigan visit. She stormed out of the Holly Hotel and berated then Gov. Fred Warner for not enforcing dry laws. Warner beat a hasty retreat in his motorcade and, according to the legend, Nation then proceeded to smash up the Holly Hotel’s bar in her trademark fashion. She continued her tour of destruction in Detroit, visiting Considine’s Saloon on Monroe Avenue, which had been shut down just days before for hosting illegal gambling. “A gilded hell,” she declared it.

Nation’s unique brand of fire and brimstone, combined with her impressive physique (she stood nearly 6 feet tall), drew large crowds eager to witness the spectacle of a sexagenarian smashing up private property.

With her typical fiery rhetoric, Nation concluded on her visit to Detroit: “The saloon is the nearest hole through which to crawl to hell. … License for drink is anarchy, a black conspiracy. It’s a license for insanity and murder.”

Getting Religion and Business on Board

The Michigan Catholic Magazine agreed. “Vote for the saloon if you want future generations to be shriveled, bloodless, prematurely decayed creatures. … Vote against the saloon,” it adjured readers in 1911, “if you wish to build up a race of giant, healthy manhood and glorious womanhood.”

By and large, though, the Temperance movement was primarily led by Protestant evangelical ministers and churchgoers. Billy Sunday’s massive rallies combined P.T. Barnum-style theatrics with zealous threats of Armageddon if Detroiters continued their sinful drinking. Sunday spent the better part of election season of 1916 hosting his “tabernacle” in Detroit. A mobile tent, altar, and conversion station all in one, Sunday’s tabernacle could hold up to 10,000, and thousands more spilled into city streets. The collection plate passed at Sunday’s gatherings measured 2 feet across and 10 inches deep; on his final day of speaking in Detroit, Sunday gathered $50,000 from an estimated 50,000 worshippers. He claimed to have hosted over two million people in metro Detroit.

Prohibition and suffrage went hand in hand, and many thought women would quickly vote to banish saloons.

Cadillac founder Henry Leland gifted Sunday with a new car worth $8,000 during his stay at Kmart founder S.S. Kresge’s Boston Edison mansion.

Some Detroiters were more invested in the Temperance movement than others. Henry Ford, S.S. Kresge, and other industrialists backed Prohibition. They argued it would lead to higher attendance, fewer accidents, and greater productivity. They weren’t wrong: In testimony before Congress just one month after Michigan went dry, Ford reported a decrease in absenteeism from 2,620 in April 1918 to 1,628 in May.

Detroit’s industrial capability gained increasing importance as American involvement in World War I became inevitable. The Revenue Act of 1913 replaced liquor levies as the government’s main source of income. Even before entering the global conflict in April 1917, the U.S. lent its support to the Allies in the form of loans of money and munitions, many of which were cranked out of Detroit factories.

A wave of anti-German sentiment fueled by the war allowed Dry advocates to stoke the fires of xenophobia. Ads and propaganda campaigns touted a strict either/or decision: patriotism or beer, the soldier or the saloon. Most of the city’s brewers were of German-American descent, and Drys presented beer as a tool in the hands of the Kaiser to weaken strong American boys and undermine national security.

The Supply Dries Up

As Election Day loomed in 1916, the Wets weren’t quite ready to give up. On Nov. 7, voters across the state chose between Home Rule — in which each municipality could choose to abolish liquor — and statewide Prohibition, to be added as an amendment to the state Constitution.

In a spectacle to match those of Billy Sunday and Carrie Nation, voters overwhelmed the polling stations and brawled in the streets. Ballots went missing or were found stuffed by the hundreds, and a fist fight between WCTU marchers and Wet campaigners was narrowly avoided at one precinct by the swift intervention of police forces.

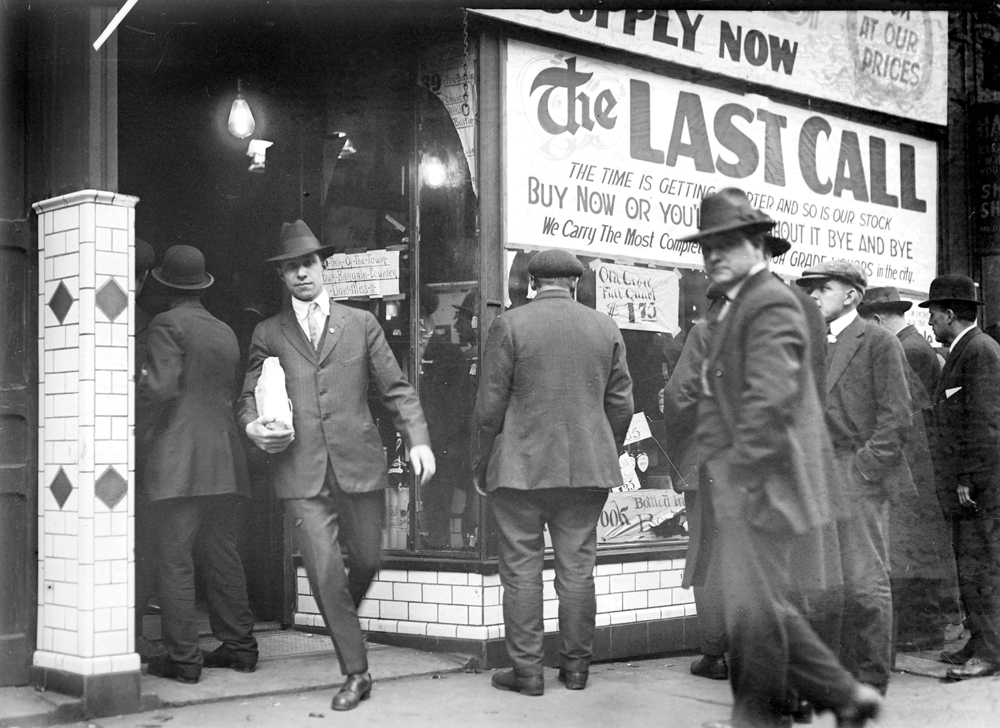

Prohibition prevailed: Michigan voted by a hefty margin to dry out beginning May 1, 1918. Although the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol was prohibited, a loophole at first allowed for private in-home consumption of liquor already possessed before May 1. At the end of April, the Detroit Free Press noted that “[B]one dryness seems to be coming to the people of Michigan with a sort of creeping sensation,” as private citizens and clubs hurried to stash enough whiskey and beer to last as long as possible.

By Tuesday, April 30, many bars had completely run out of alcohol to serve patrons. The Cafe Frontenac on Monroe Avenue held a wake for John Barleycorn. Hundreds were turned away because they didn’t have tickets; after the event, a remodeled and rebranded Frontenac Restaurant opened with an emphasis on fine dining and soft drinks. They were luckier than many: 10 of the 13 bars on Monroe had closed before midnight the Saturday due to the shortage. On one saloon, a hastily scribbled sign read simply, “No More.”

“Old King Alcohol died a miserable death in Detroit, Tuesday night, a grim, sodden death in the midst of a drizzle of rain,” mourned one observer.

The University of Michigan’s student newspaper, The Gargoyle, penned a flippant poem:

Let us view with consternation

All the sable-hued damnation

That will follow with the passing of the booze.

Shed a tear for glasses clinking

Cry an end to night of drinking

And all songs about our wabbling [sic] in our shoes.

The Experiment Fails

Detroit’s steady stream of booze never stopped or even slowed down. It simply went underground — sometimes literally. Within days, Dixie Highway near Monroe, recently paved, was jammed from sunup to midnight with revelers on their way to and from Toledo. Law enforcement was unable and often unwilling to keep up with the streams of whiskey flowing along the “Avenue de Booze,” as it became known, and enforcement was equally ineffectual.

The first men arrested for bootlegging under the new law were arrested in Flint on May 5: two men caught smuggling 85 pints of beer on May 3. Even the celebrated teetotaler Kresge couldn’t avoid association with bootleggers. His son Howard was arrested multiple times, first for drinking at a high school dance at the Book Cadillac Hotel, and several other times for drinking and driving, and was also put on probation at the University of Michigan.

Detroit’s easy access to Canada and its whiskey distilleries created the Detroit-Windsor “Funnel,” through which an estimated 75 percent of the country’s whiskey supply flowed during Prohibition. According to historian Daniel Okrent, in the first seven months of 1920 alone, 900,000 cases of liquor made its way to Windsor from the rest of Canada. This became a one-way supply enough for 215 bottles of booze for every man, woman, and child in the area.

Hiram H. Walker even created a flat-backed “bootlegger’s bottle” for easier storage under clothing for visiting Detroiters. Downriver, resourceful French-American families built secret empires by darting across the river and smuggling into the hundreds of hiding spots in the marshlands. The most colorful of these, Arthur “Mushrat” La Framboise and his brother “Whiskey Jack,” made hundreds of dollars a day smuggling beer and whiskey and outrunning the laughingly slow patrol boats of local and federal agents.

Prohibition in Detroit left a lasting legacy of crime, corruption, and violence. By 1933, a weary nation gave up and agreed that it simply hadn’t worked.

Detroit had known this almost from the start. “When the story of today takes its place in history,” one Dry campaigner boldly and erroneously predicted in 1918, “it will relate how the people of Michigan broke the backbone of the liquor industry in the United States.” Instead, Prohibition nearly broke the back of Detroit, as illegal economies soon swamped legitimate industries and murder rates soared.

The idea of a dry nation was a flop, and in April 1933, Michigan became the first state to ratify the 21st Amendment, repealing the failed experiment that was Prohibition.

Surviving Speakeasies

By their very nature, Detroit area speakeasies skirted detection. Many spots survived by converting to “lunch counters” and “cafes.” Many speakeasies endured without getting caught. Others caved in to repeated raids, like the Bucket of Blood. Cliff Bell managed four joints during Prohibition, but the current location officially opened in 1935. Here are a few gems likely to have served a drink or two.

Andrews on the Corner marked its 130th anniversary in 2017. This spring, the Atwater Street bar toasts 100 years of ownership by the same family. Tom Woolsey’s grandfather, Gus Andrews, opened in 1918, no doubt to take advantage of the increased Hiram Walker distillery ferry traffic nearby.

Abick’s Bar in Southwest Detroit is the city’s longest continuously family-owned bar. George and Katherine Abick bought the Stroh’s-affiliated saloon from Katherine’s uncle in 1919. The tin ceilings and original cash register remain, and a few years ago, a tantalizing hint to a criminal past was discovered in the basement: two barrels of whiskey.

Two Way Inn in Nortown at Mount Elliott and Nevada streets first opened as a general store and tavern in 1876 when the area was a stagecoach stop. During the 1920s, a dentist operated out of the building. Dentists, along with other medical doctors, were allowed to prescribe whiskey so the building saw a steady flow of “patients” seeking comfort.

Ye Olde Tap Room on the city’s east side got its start due to its proximity to easy transportation routes. It only served alcohol legally for a year or so before Prohibition started, but gamblers could find plenty of card games and place bets on the second floor or drink in peace in the basement bar.

The Painted Lady Lounge is known to a generation of punk rock aficionados as the former site of Lili’s 21 Club, but it’s been around a lot longer than that. A previous owner removed a large bar from the underground space.

Frank’s Eastside Tavern in Mount Clemens looks much more like a speakeasy than most people picture when they think of the word. Rather than swanky wall décor and muted lighting, the bar is housed in the basement of a farmhouse. It’s much easier to avoid detection if your bar doesn’t shout, “raid me.”

Jacoby’s Biergarten has been a proudly German gathering place since it was established in 1904, and it’s not likely that the taps really ever stopped flowing, despite the depth of anti-German sentiment that pervaded Detroit at the time.

Nancy Whiskey in Corktown opened in 1902 as Digby’s grocery store for the Irish-American neighborhood. Within a few years, though, liquor sales outstripped food sales. While there’s no hard proof that it was selling booze during Prohibition, a 1930 holdup in the grocery store netted the bandits a hefty sum of $20.

Tommy’s Detroit Bar on Third and Fort has weathered the recent closure of nearby Joe Louis Arena just as it survived of Prohibition: by supplying thirsty patrons with plenty of the wet stuff. A 2012 archaeological dig by Wayne State University uncovered hard evidence of a Purple Gang gambling room in the basement of this 19th century building, as well as the collapsed remains of a tunnel that allowed those in the know to access the space.

Web Extra: A Brief History of Cleaners and Dyers War

The feud marked the rise of Detroit’s infamous Purple Gang

By Emily Ridener

When we talk about organized crime during Prohibition some think of the mafia in New York or Chicago but there was an anchor in between the two that controlled 75 percent of the liquor entering the United States: The Purple Gang.

Other than a quick reference in Elvis Presley’s popular hit “Jailhouse Rock,” many outside Southeast Michigan have never heard of the Purple Gang. The predominantly Jewish gang burned hot and fast, controlling the city for less than 20 years. But the violent feud that marked the gang’s uprising had little do with bootlegging at all: the Cleaners and Dyers War.

Michael Newton’s book, Mr. Mob: The Life and Crimes of Moe Dalitz, details the beginnings of the feud, explaining how a familial connection led to the Purple Gang’s involvement in racketeering. Between 1924 and 1925, Francis Martel, president of the Detroit Federation of Labor, hired Ben Abrams from Chicago to organize Detroit laundries into a “price-fixing consortium,” known as the Wholesale Cleaners and Dyers Association (WCDA). Charles Jacoby Jr., vice president of Michigan’s largest wholesale laundry, was the brother-in-law of the Bernstein brothers (leaders of the Purple Gang). Naturally, he also became the president of the WCDA.

Of course, the WCDA did very little for cleaners, instead using members’ dues to further the Purple Gang’s other illegal ventures. After the WCDA doubled the wholesale cleaning rates, members of the Retail Tailors Union went to the Detroit Labor Temple for a meeting chaired by Martel. The meeting didn’t go well, with Martel slamming a brick on the podium anytime a tailor stood up and telling them to shut up. After this, the tailors came together to form a partnership between Empire Cleaners and Dyers and Novelty Cleaners to compete with the WCDA.

In March 1928, an issue of the Detroit Free Press cited the Cleaners and Dyers War began in October 1925 with the “dynamiting of the Empire Cleaners and Dyers plant.” In just over two years, two men had died, and police records showed $161,900 (close to $2.4 million today) in damages had been done to various properties.

The final nail in the coffin of the Cleaners and Dyers war was when Sam Polakoff, vice president of the Union Cleaners and Dyers, was kidnapped and murdered on March 22, 1928. Judge Charles Bowles issued arrested warrants for Jacoby and many members of the Purple Gang including the three of the Bernstein brothers, Irving “Little Irv” Shapiro, and Abe “Angel Face” Kaminsky.

Jacoby and nine Purples were put on trial for extortion in June 1928, although all were acquitted by September. The case marked the first major legal victory for the Purple Gang and ultimately the racketeering help fund the gang, widely expanding their influence. Over the next few years, the Purples controlled the entire Detroit underworld, including the gambling and drug trade. Notably, some members also lent a helping hand to their business partner, Al Capone, during the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929.

Still, the gang wouldn’t last long. While there is no officially recognized event that caused the end of the organization (although some argue that the Collingwood Manor Massacre in 1931 started the downfall), by 1935 the Purple Gang was accepted to be inactive.

|

|

|