Robert Hudson Tannahill belonged to a storied group of bachelor collectors from Detroit who, although they never married, nevertheless had a lifelong, loving spouse: art.

In fact, Tannahill sometimes referred to Picasso’s 5-foot-tall Woman Seated in an Armchair, which hung on the stairwell of his Grosse Pointe Farms home, as “the mistress of the house.”

Along with such unmarried Detroit collectors as Charles Lang Freer, W. Hawkins Ferry, and John S. Newberry Jr., Tannahill devoted his life to acquiring top-flight art. Tannahill’s bequest to the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) was not only extensive — it included Modernist, Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and German Expressionist oils, watercolors, and drawings — but also embraced modernist and classic sculpture, African and Pre-Columbian art, along with an exquisite collection of 18th-century French silver.

It’s difficult today to think of Matisse or Cézanne as modern painters, but in 1930, when Tannahill started collecting those masters in earnest, they were considered daring — not so much in Europe, but in America — and most definitely in conservative Detroit.

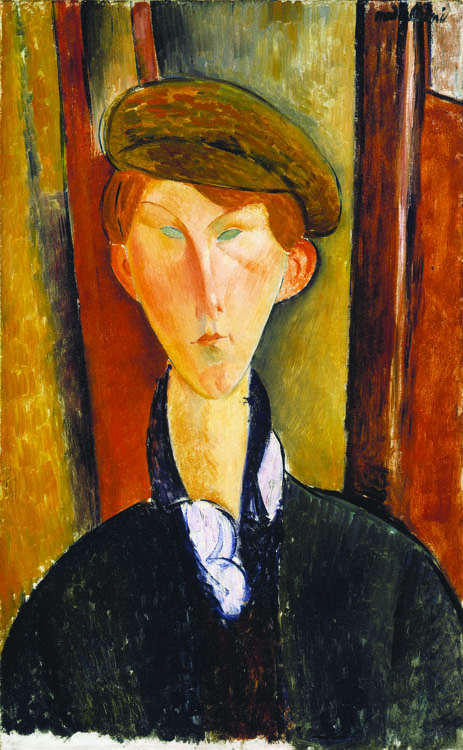

During his life, Tannahill donated close to 500 items to the DIA. Upon his death in 1969, he left a veritable bonanza to the museum: another 557 works, including some that have become among the most recognizable and highly prized paintings in the DIA’s collection, mostly modernists but old masters, too: Picasso’s Melancholy Woman, Head of a Harlequin, and Woman Seated in an Armchair; Matisse’s Poppies and Coffee; Renoir’s Seated Bather and The White Pierrot; El Greco’s Madonna and Child; Cézanne’s Portrait of Madame Cézanne and The Three Skulls; Gauguin’s Self-Portrait; Degas’ Violinist and Young Woman; Modigliani’s Young Man with a Cap; Corot’s Young Girl with a Mandolin; van Gogh’s The Diggers; Seurat’s shimmering View of Crotoy, Amont; and Chardin’s tiny but ravishing Still Life.

Gifts That Keep Giving

If that weren’t bountiful enough, Tannahill also established the Robert H. Tannahill Foundation in 1961, which benefits eight organizations: the DIA, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the College for Creative Studies, the Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, Detroit Artists Market, the Grosse Pointe War Memorial (which once served as the DIA’s satellite exhibition space), Christ Church Grosse Pointe (where Tannahill, an Episcopalian, worshipped), and the Episcopal Diocese of Michigan.

The DIA gets the lion’s share — 50 percent — so in addition to the roughly 1,000 objects he donated, Tannahill is still giving in perpetuity as the museum continues to purchase art and decorative items provided by the fund.

As a result, Tannahill’s name appears all over the museum on plaques acknowledging items he gave or those that have been acquired from his fund. In addition, the modernist wing is named after him, and the DIA has designated those who leave the museum in their wills as belonging to the Robert H. Tannahill Society.

“When you walk through our modernist galleries, it seems that every other work of art is from his bequest collection, was a gift before his death, or was purchased from his fund,” says DIA Director, President, and CEO Graham W. J. Beal in an interview in the museum’s Kresge Court.

Beal calls the Tannahill bequest “an important, classic modernist collection that was very broad-ranging because it also included sculpture and African art.

“I think the bequest really improved the quality of our African art,” Beal says. “The African art that the museum already had was pretty awful, by and large. Some very high-quality material came in after his death.”

Indeed, Tannahill was among a rare handful of collectors drawn to African art in the early 1930s.

According to an essay by Ellen Sharp, the DIA’s former curator of graphic arts, the bequest also filled in other gaps in the museum’s collection. It boosted the number of Picasso drawings and added a drawing by Georges Braque. Tannahill’s collection also added watercolors and drawings by German Expressionists Otto Dix and Otto Mueller, whose works in those media were not previously represented at the museum.

From May 13-Aug. 13, 1970, the DIA mounted an exhibition, The Robert Hudson Tannahill Bequest to the Detroit Institute of Arts, along with publishing a hardbound catalog to accompany the show. To the vast majority of visitors, it was their first exposure to this major collection, for unless you were a fortunate visitor to Tannahill’s home, these works hadn’t been seen anywhere for years. Despite his largesse, Tannahill was loath to lend art he kept in his home, preferring to be surrounded by their beauty. Still, he enjoyed entertaining friends and family there, which one friend told the Detroit Free Press evoked “the atmosphere of the great French salons.”

In a New York Times story on the 1970 DIA bequest exhibition, John Canaday wrote that Tannahill “was far from a hermit, but he avoided strangers and seldom showed his collection. … Those who were lucky enough to see it were never given any hint that they were being awarded a special favor.”

One lucky guest in the Tannahill house was Joseph L. Hudson Jr., his first cousin once removed.

“It was like a museum,” Hudson says from his office in downtown Detroit, where he serves as trustee of the Hudson-Webber Foundation. “He was proud of every little element, and it wasn’t just major works of art; there were a lot of small, elegant pieces. Pretty much everything ended up at the DIA.”

A Buffalo, N.Y., native, Hudson, a co-executor of the Tannahill estate, came to Detroit to live in the 1950s and worked his way up at the J.L. Hudson Co. In 1961, not quite 30, he became president of the giant retailer.

Hudson, who admits he “wasn’t very culturally refined” as a young arrival here, says he was warmly welcomed by his cousin, who didn’t seize the opportunity to browbeat or impress his relative with his artistic knowledge.

“He never did any preaching; he was just very charming and had a wonderful curiosity about my wife and me.”

Tannahill’s love of art must have rubbed off on Hudson and his wife, Jean. Both were on the DIA’s board of directors and continue to be emeritus members. Hudson also served as president of the Detroit Arts Commission. In 1963, Hudson opened the venerable J.L. Hudson Gallery on the seventh floor of the flagship downtown store. “That was my baby,” Hudson says. The space sold choice art and also hosted well-regarded exhibits.

The Man Behind the Art

But who was Robert Hudson Tannahill, who died 45 years ago this month? And where did he derive his shrewd aesthetic sense?

Tannahill was a cultivated but shy man, whom Jane Schermerhorn in a 1962 column in The Detroit News called “a man who all his life has courted the background. Almost without identification, he has served Detroit and its people long and well.” He left this enormous legacy and avoided the spotlight in life, but Tannahill’s name endures today, if only as a shadowy footnote.

A cursory Internet search provides scant information, even flagrant misinformation. For instance, Tannahill is described on Wikipedia as being the nephew of Eleanor Ford, an inaccuracy picked up by several other sites. Tannahill, three years older than Ford, was, in fact, her first cousin.

Tannahill’s great uncle was the Scottish poet and songwriter Robert Tannahill (1774-1810), who was a near contemporary of Scotland’s best-known poet and lyricist, Robert Burns.

For many Detroiters, Tannahill’s middle name rings a familiar if nostalgic bell, because he was the nephew of Joseph Lowthian Hudson, founder of the celebrated but departed Detroit retailer.

Despite his famous pedigree, Tannahill chose to remain out of the limelight. In his remarks at a Tannahill Memorial Exhibition at the Grosse Pointe War Memorial in 1978, Frederick Cummings, former director of the DIA, said of the collector: “He was extremely modest, even shy. He not only did not want publicity — he actively avoided it.” Yet Cummings also mentioned Tannahill’s “alert, crisp wit” and his ease in conversation.

At that same exhibition, William Bostick, a longtime DIA administrator and secretary and an artist in his own right, wrote that the reserved Tannahill was nevertheless “devoid of stuffiness or pomposity, and he was ‘Bob’ to everyone who knew him well.”

Early Years

Tannahill, an only child, was born in Detroit in 1893 to Anna Elizabeth Hudson and Robert Blyth Tannahill. She was one of the six siblings of J.L. Hudson and was a beneficiary of his estate upon his death in 1912. Her husband was director of advertising for the J.L. Hudson Co., and ascended to vice president.

Financially well-off, the family lived at some of the city’s finest addresses: first, in the 1890s on Peterboro Street, then Woodward Avenue and East Boston Boulevard. After the death of his mother (1921) and father (1925), Tannahill inherited his parents’ fortune and moved to Iroquois Street in Detroit’s Indian Village. Then, to accommodate his sprawling collection, he built a home on Lee Gate Lane in Grosse Pointe Farms in 1947. Until his death, he remained a major stockholder in the J.L. Hudson Co., though there’s no evidence that he ever worked at the retailer.

Tannahill was always close to his cousin Eleanor Clay Ford from the time they were children. As adults, they shared a love of art and culture. After the death of Ford’s husband, Edsel, in 1943, Tannahill often was his cousin’s escort at social and cultural events. She frequently accompanied Tannahill on his twice-yearly trips to New York, where they saw operas and Broadway plays, and consulted with art dealers.

Though demure and a rather tall and big-boned fellow, Tannahill wasn’t bashful about stepping out on the dance floor at social occasions. The Detroit Free Press reported that he “always seemed to enjoy dancing and has acquitted himself well on the ballroom floor.”

Tannahill was also fond of Edsel Ford. A talented auto designer, Ford became an avid art collector. Tannahill was the same age as Ford, and they were classmates at the prestigious Detroit University School, which in those days was on Parkview in Detroit, just off East Jefferson Avenue. In addition to his love for culture, Tannahill was also a sportsman in his youth. While at the all-male University School, he won second prize in the handicap meet for the 30-yard dash in 1910.

Tannahill then attended the University of Michigan from 1911-15 and went on to get his master’s from Harvard in 1916. It was at U-M that his love of drama took flight. In the 1920s, Tannahill wrote four plays, and copyrighted two of them. Although there’s no record of their performance, a reading in the DIA Research Library and Archives of his one-act play Their Dead, set in France after World War I, shows obvious talent. As late as 1929, Tannahill listed his occupation on his passport as “playwright.”

Among the other items in the DIA archives is Tannahill’s scrapbook, which includes programs from the Cercle Français when he was at U-M. Tannahill appeared in numerous performances mounted by the organization, and the plays appeared to have been performed in the original French. In a 1914 review clipping, presumably from the university’s newspaper, the young thespian “showed considerable skill” in Henry Bernstein’s L’Assaut. That he was comfortable in French makes sense. Tannahill worked as a civilian army service translator at a base hospital in France in 1917-18. Tannahill remained a lifelong Francophile, and his bequest shows a marked bent for French artists. He traveled frequently to Europe to broaden his education, sometimes with a man who was the most important artistic influence in his life.

His Great Mentor

A shrewd eye and a heightened artistic sensibility are essential ingredients in the making of an art collector. Independent study and coaching by art dealers help, of course, but Tannahill’s friendship with William Valentiner, the DIA’s director from 1924-45, deepened his understanding and appreciation of art.

Valentiner, a native of Germany, was a scholar of Dutch and Flemish old masters, but he also possessed a strong interest in modern German Expressionists and other contemporary artists, particularly the wonderfully strange work of Swiss master Paul Klee. Valentiner also had a famous artist son-in-law. His daughter, Brigitta, married sculptor/designer Harry Bertoia when the artist taught and worked at Cranbrook.

“Tannahill had a great guide in Valentiner,” Beal says. “I’m sure he was responsible for getting him interested in German Expressionists. I think Valentiner had to have been in a sense his teacher, introducing this young man to such cutting-edge art.”

Valentiner also was a friend and mentor to Edsel and Eleanor Ford, and according to Margaret Sterne’s 1980 biography, The Passionate Eye: The Life of William R. Valentiner, he was a frequent guest in their home.

Hudson also attributes Tannahill’s and the Fords’ elevated interest in art to Valentiner. “Their becoming interested in art was almost simultaneous with Valentiner coming to Detroit,” he says. “They were all friends.”

It was Valentiner who engaged Mexican artist Diego Rivera to paint the Detroit Industry frescoes (bankrolled by Edsel Ford) in 1932. Tannahill met Rivera and commissioned him to paint his portrait. Rivera painted two oils, which, along with a sketch, are included in Tannahill’s bequest.

One painting and the sketch show a seated Tannahill wearing rimless spectacles. Rivera’s other portrait depicts Tannahill from the neck up, without his glasses. His visage is stern and serious, but the seated portrait may give the more accurate reflection of Tannahill’s personality: erudite and aristocratic, but with an undeniable sensitivity.

A Champion of Detroit

Tannahill began donating items to the DIA in 1926. Before long, he was serving on several important artistic posts. From 1927 until his death, he was honorary curator of American Art at the DIA. He became a member of the Detroit Arts Commission in the early ’30s, and briefly served as its president in 1962. He was also a trustee of the DIA’s Founder’s Society since 1931 and was one of the organizers of the Friends of Modern Art in 1933.

Because of his inheritance and stock dividends, Tannahill didn’t have to work, but he stayed busy until the end of his days active in arts organizations.

Tannahill was a proponent of the world’s great modern art, but he was also devoted to what was created in his own backyard. He was one of the founders of the Detroit Artists Market in 1932, an organization that thrives today on Woodward in Midtown Detroit. In its early days, it was known as the Young Artists Market, and Tannahill was a staunch supporter of artists whose talents were vast but whose pocketbooks were limited and names unknown.

The collector may have spent hefty sums on Picassos and Renoirs, but Tannahill also bought art made in Detroit. In his bequest there are works by such local artists as Sarkis Sarkisian, John Carroll, and Charles Culver. And, at a time when many collectors ignored African-American artists, Tannahill embraced them. Included in his bequest is Charles McGee’s haunting charcoal drawing Window Watchers and abstract artist Robert Murray’s Sit’n and Wait’n.

Tannahill was a leader in the establishment, in 1932, of the exhibition space of the Detroit School of the Society of Arts and Crafts on Watson Street, now known as the College of Creative Studies. In those financially lean years in the thick of the Great Depression, Tannahill plugged away at presenting avant-garde exhibitions to Detroit.

Aware of the monetary hurdles of launching a contemporary exhibition space during such trying times, Tannahill often took on grunt tasks himself, according to William Bostick, who in 1978 wrote of Tannahill and the gallery: “They presented 50 exhibitions, many of which were milestones in showing contemporary art to the Detroit public.

“The budget was minuscule, and Tannahill did much of the physical labor himself with occasional assistance from students and the janitor.”

Tannahill was fond of saying “Modern art always needs believers.” In that spirit of converting contemporary art disciples, he organized a memorial exhibition devoted to Paul Klee in 1940 at the Watson Street gallery. Valentiner, a Klee buff, delivered a lecture. The effort was a flop. The public neither understood nor liked Klee’s works. Only one watercolor sold, and Tannahill bought it.

In the late 1930s, Tannahill mounted another unusual exhibition at the Society. In the summer of 1937, he and Valentiner visited Munich and were appalled by an exhibit of what the Nazi regime deemed “Degenerate Art.” Art by German Expressionists and other modernists were confiscated from German museums and put on display so the German people could see what was artistically repugnant to the Nazis. Shortly thereafter in Detroit, Tannahill decided to exhibit art by such “degenerates” as Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Käthe Kollwitz, and Lyonel Feininger (though the latter was American-born). The exhibition alerted Detroiters to what was happening in Germany. It was also an opportunity for them to decide for themselves if the art was degenerate.

An Enduring Legacy

There are few more telling things about a person’s character than the small, unheralded gestures that underscore one person’s kindness to another.

Among the archived letters in the Tannahill papers at the DIA is one January 1968 missive by Frederick Cummings, who was then the museum’s executive director; he became director in 1973. It was an emotional thank-you note to Tannahill, who had dropped in at the museum on a Saturday when Cummings was out of the office. On Cummings’ desk he left an English 17th-century silver spoon, along with a brief note. Cummings was emotionally floored, admitting to “a thoroughly choked voicebox” and writing that he had no idea Tannahill knew of his passion for collecting antique silver spoons. However, Tannahill made a habit of learning his friends’ likes and hobbies, and then sometimes indulging them with gifts.

In June 1969, three months before Tannahill’s death, the DIA named the American galleries after him. More recently, the museum conferred that wing’s designation after collector and industrialist Richard A. Manoogian and in turn affixed Tannahill’s name to the modernist wing — a more fitting homage since Tannahill’s greatest affection was for art of more recent times. Tannahill must have been touched by the honor, but didn’t have much time to savor it. On Sept. 25, 1969, at age 76, he died of congestive heart failure. Funeral services were held at Christ Church Grosse Pointe.

Forty-five years later, Tannahill’s legacy to Detroit continues to be almost palpable in the marvelous works he left to the DIA, even though his self-effacing nature seemed to be at odds with such a magnanimous and dramatic act.

In his many trips to the DIA, Tannahill must have read — and taken to heart — the words chiseled into the marble façade above the Woodward Avenue entrance as he pondered his bequest: “Dedicated by the people of Detroit to the knowledge and enjoyment of art.”

Bostick neatly but elegantly summed up Tannahill’s lasting and priceless contribution in his remarks at the Grosse Pointe War Memorial exhibition in 1978:

“Robert Hudson Tannahill has written his autobiography boldly and permanently with his visual legacy to the city.”

An autobiography is often a colossal exercise of ego, but in Tannahill’s case it isn’t so much one man’s life story, but an enduring tale of the power and immortality of art and how it can transform all people’s lives. That was, and is, his gift.

|

|

|