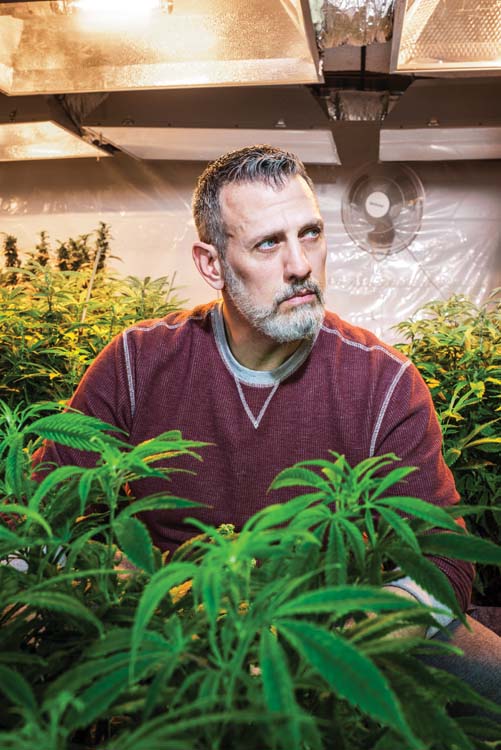

Robert Gage Amsler has done many things in his life. As a 1st Recon combat medic attached to the Marines, he’s healed soldiers’ wounds while fighting off a foreign enemy. As a Detroit paramedic, he’s read the notes of suicidal 16-year-olds and removed the nooses from their necks. He’s faced the fists of drunken stepfathers, the unforgiving deserts of Iraq and Afghanistan, and the hostile streets of Detroit. He’s been a bouncer, a firefighter, a government contractor, and most recently, a medical marijuana caregiver.

Robert Gage Amsler has done many things in his life. As a 1st Recon combat medic attached to the Marines, he’s healed soldiers’ wounds while fighting off a foreign enemy. As a Detroit paramedic, he’s read the notes of suicidal 16-year-olds and removed the nooses from their necks. He’s faced the fists of drunken stepfathers, the unforgiving deserts of Iraq and Afghanistan, and the hostile streets of Detroit. He’s been a bouncer, a firefighter, a government contractor, and most recently, a medical marijuana caregiver.

He’s also suffered post-traumatic stress, which has been a part of Amsler’s life for as long as he can remember. Like many of his fellow veterans, the 45-year-old Amsler, whose bodybuilder frame is visible even through a baggy sweatshirt, sought help from the government he served when his PTSD ramped up seven years ago.

But when VA doctors put him on what’s known in the veteran community as the “combat cocktail” — a mix of drugs used to combat PTSD and the side effects of the drugs used to treat it — Amsler didn’t like how they made him feel.

“It became hard to live in a constant screen of lethargy, shielded from myself by a chemical mixture that swished around my brain,” Amsler writes in his book The Strains of War, a memoir he published this past September.

Seeking an alternative, Amsler smoked pot for the first time in 2009 after a four-year stint in Iraq. The experience was revelatory for him and encouraged him to become a marijuana caregiver in order to provide the experience for others. He became registered with the state of Michigan to legally grow pot plants and provide medicine for up to five other patients. Amsler took his work seriously and printed a monthly newsletter of information on his new strains and edible offerings. He even baked large batches of pot cookies and handed them out for free.

“The more I realized it was medicine, the better it made me feel to give it out,” Amsler says.

Amsler’s not alone in feeling this way, as more veterans both nationally and locally are turning toward marijuana to help treat their PTSD.

The stakes are high. The VA estimates that somewhere around 20 veterans die from suicide each day. And a CBS report found that veterans have a 33 percent higher rate than non-veterans when it comes to accidental overdoses from prescription drugs.

According to Cort Kwiecinski, owner of the Detroit Grass Station, a medical marijuana dispensary in New Center, veterans are one of his shop’s most consistent customer blocs; many come in every week. He offers a 10 percent discount to all veterans who get their medicine from his establishment, and he’s also worked with business partner and grower Solomon Laman to develop strains of pot that target common veteran ailments like PTSD and sleep problems.

According to Cort Kwiecinski, owner of the Detroit Grass Station, a medical marijuana dispensary in New Center, veterans are one of his shop’s most consistent customer blocs; many come in every week. He offers a 10 percent discount to all veterans who get their medicine from his establishment, and he’s also worked with business partner and grower Solomon Laman to develop strains of pot that target common veteran ailments like PTSD and sleep problems.

In addition to the therapeutic effects of cannabis, dispensaries also offer veterans an accepting environment that works to destigmatize pot use and provide a welcoming place to socialize.

“Culturally, dispensaries are like a barbershop,” Laman says. When customers pop in, they can spend a few minutes getting to know the operators, learn about the various types of medicine available for purchase, and associate with fellow patients who are using cannabis to cope with problems traditional medicine has failed to treat.

Eldridge Blake is one veteran who frequents the Detroit Grass Station, along with several others who live nearby at the Piquette Square veterans housing center on Brush Street.

Blake began serving in the Vietnam War starting in 1974, but didn’t see combat as the U.S. disengaged from the police action there. Nearly 20 years after returning home safely, Blake was caught in the crossfire of a Detroit street shooting, suffering seven gunshot wounds. He spent a year in the hospital learning to walk again, but the pain of the shooting stayed with him.

His right arm, where multiple bullets shredded nerves and bone, still bothers him. “Sometimes, this arm, I have to hold it, it aches so much,” Blake says. “To relieve the pain, I have to squeeze it. It’s in the bones. You learn to bear with it.”

For Blake, part of bearing with the pain also involves smoking the occasional joint. A fellow veteran at Piquette Square turned him on to medical cannabis after voters approved the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act in 2008.

The Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs to treat PTSD are sertraline (Zoloft) and paroxetine (Paxil): two antidepressants whose side effects can include chronic pain, hallucinations, thoughts of suicide, and increased aggression. Veterans are often prescribed other drugs to combat these side effects, thereby creating the combat cocktail.

Such was the experience for Dakota Serna of Flint, a former Marine Corps rifleman who fought in the Second Battle of Fallujah. The 2004 engagement escalated into some of the IraqWar’s most intense fighting, and after the battle, Serna began suffering nightmares. While in Iraq, he tried to commit suicide with his service M16. The weapon jammed twice, thwarting his attempt.

Like Amsler, Serna was originally prescribed a mix of drugs to combat his PTSD, some of which did more harm than help. According to Serna, Zoloft “screwed with his insides,” giving him stomach cramps and diarrhea while also failing to alleviate his irritable mood.

And after reading the side effects sheet for divalproex sodium (Depakote), a supplementary drug prescribed as part of his combat cocktail, Serna decided to take himself off of the pills.

“Basically, the sheet said ‘Don’t give me this,’ ” Serna says. “ ‘If you have thoughts of rage, homicide, suicide, don’t take this medication.’ ”

Not long after the switch, a friend handed Serna a joint; he put away the pills for good. “I never felt like the pills affected my head,” Serna says. “But when I smoked, everything changed.”

Serna works as an activist for medical marijuana on panels at the High Times Cannabis Cup in Colorado and at veterans organizations nationwide.

Over the years, science’s view on the effectiveness of cannabis treatments for PTSD has been mixed. A Yale study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry followed nearly 2,300 veterans from 1992 to 2011 and observed relationships between cannabis use and PTSD severity. The study ultimately concluded that cannabis users were significantly more likely to display worse treatment outcomes and more violent behavior.

But even if science seems to indicate that weed may not help with treatment of PTSD, the data — and testimonials like Amsler’s and others — show that cannabis can help veterans feel better.

Amsler is adamant that cannabis saved his life, and today, he has a grow operation business in North Branch. It has helped relieve his personal symptoms, but has also grown to represent much more to him: the ability to heal neglected people and bring them together.

Moving forward, Amsler hopes to turn his 34-acre property into a “420-friendly veterans center” where vets can go for camaraderie, to relax, and to use their medicine to combat their mental and physical war wounds, just as he has.

“I want to use my life as a footprint for others,” Amsler says. “Moving here, after everything I’ve been through, I feel safe here. For me, it’s like cannabis. I’m getting back to nature. This heals. I’m off every medication I’ve ever been on.”

|

|

|