In the bleak and frigid predawn hours of Dec. 16, 1885, several men on Fort Street noticed a reddish-amber glow pulsating in the distance.

The men came upon a hellish scene. The Knochs’ farmhouse was ablaze, turning the inky night into garishly lit day. A stiff wind whipped the flames and spread the mingled odor of roasted turnips and burning flesh. Would-be rescuers futilely tossed snow and helplessly watched two figures framed by a window melt away like wax. Late-arriving neighbors formed a bucket line, hauling water from the creek a quarter-mile away, but it was too late. Gone were Frank Knoch, his wife, Susan, and their sons, 2-year-old George and baby Frank — all evidently done in by a faulty chimney or exploded oil lamp.

The following day, however, as the funeral cortège filed past the smoldering ruins on its way from St. Paul’s Lutheran Church to Woodmere, authorities were discovering that the family had not been the victims of an accident, but of an incomprehensible atrocity. Over the next several weeks, the Knoch massacre dominated local news and conversation, its twisted storyline even covered in The New York Times. The Detroit Free Press called it “the most pitiable and horrible tragedy that has been recorded against Wayne County in years.” Then it faded away.

Several generations later, “The Springwells Horror” fails to ring a bell with local historians and cemetery buffs. No published works mention it, and the Knochs’ gravesite is not part of any organized tour of Woodmere’s sprawling grounds. The oversight becomes more understandable when trying to locate the family plot one winter day. After some fruitless wandering in the snow, a couple of gravediggers fetch a section map and interment card from the cemetery’s office. The slaughtered family was buried without a stone, one of them explains. Using nearby tombstones as a guide, coordinates are roughly determined and some vigorous boot scuffing of the slate-like turf follows. It was on a day like this that a single coffin, containing what little was left of the four victims, was blessed by a priest and then dropped into the ground, as mourners remained huddled inside their carriages.

Standing on the same frozen patch more than a century later induces dark visions. Underfoot is a row of four deteriorating wooden coffins. In addition to the one containing the victims, three others hold the remains of Frank Knoch’s parents and a brother. All died separately under violent or suspicious circumstances. Their intertwining fates comprise one of the most baffling mysteries of old Detroit, a saga of familial madness that, like the grave that holds them, has been swallowed by time.

The possibility that Frank Knoch’s family had perished as a result of an accidental fire was quickly dismissed by Wayne County physician Dr. F.W. Owen, who conducted the autopsies. Probing the charred remains, he found two .22-caliber bullets that proved to have been fired from a warped, rusted revolver dug out of the wreckage. The weapon, found beside the sewing machine, had been fired twice. “Bullets In Their Brains,” Detroit’s daily newspapers announced, and with that, the tragedy turned into a quadruple murder investigation.

Frank, 26, and his 23-year-old wife had been married three years. They were known to be hard-working and prudent, and their homestead reflected those virtues. The larders were full, the firewood was stacked, and everything “told of a hearty, healthy, happy pair, contented with their lot, good to themselves, their children and their cattle.” But then, in a flash, it was all snatched away. An intruder fired a round from a .22-caliber revolver into the left temple of Frank, shot Susan in the right temple, and then disposed of the children while turning the snug, comfortable home into an inferno. More horrifying details soon emerged. A hatchet blade was found in the cooling coals, and a second post-mortem examination revealed that it had been used to chop the oldest boy’s head into pieces. There was too little left of the baby to determine whether it had been similarly butchered. Veteran detectives speculated that the murderer-arsonist, in a hurry to flee the scene, had probably left the infant in its cradle.

George Stellwagen, the Wayne County sheriff, quickly took charge of the case. A capable man preparing to celebrate Christmas with his wife and four children, the 46-year-old German immigrant and Civil War veteran was deeply affected by the massacre. He announced that he would “leave nothing undone in searching for the guilty parties.”

Stellwagen’s first call was on Frank’s mother, Elizabeth Knoch, who lived on Dix Road, a couple of miles from Frank’s place. Elizabeth shared the family farm with four grown children, including two sons, Gustave and Herman. Gustave, 22, managed the property, assisted by Herman, 21, a powerfully built “half-wit” who had spent some time in an asylum. The mother, who dressed in black and spoke little English, had previously buried her husband and oldest son. Now she was being asked what she knew about the deaths of four more family members. As Stellwagen conversed with her in German, it developed that she didn’t know much. Neither did Gustave and Herman, who spoke reluctantly. A thorough search of the property turned up no incriminating items, although Gustave admitted that a pair of .22-caliber revolvers and box of cartridges — not of the type used in the murders — were his. He had a third pistol, but he didn’t know where it was. “There is something very strange about this family,” Stellwagen said as he left the premises.

At the same time, the sheriff was eager to speak to a Polish immigrant known only as “Aleck.” The itinerant farmhand had become angry after being let go a week earlier by Frank. Aleck, who boarded with the Knochs, presumably knew that Frank kept his money inside a drawer of Susan’s sewing machine. Aleck was last seen driving a manure wagon from Springwells to Detroit, after which he disappeared.

A coroner’s inquest was convened two days after the murders, with the large number of spectators causing the daily sessions to be moved from Judge Kurth’s courthouse to a large hall above a Fort Street saloon. Seventy-five witnesses were subpoenaed over the course of a month, including members of the Knoch family. Frank’s prosperity was no secret, as he often talked about how much his seeds, plants, and vegetables brought at market. Money was the focus of a recent argument he’d had with Gustave. Frank had made roughly $1,500 in 1885 and had about $800 in savings — impressive numbers at a time when most Americans earned only a few hundred dollars a year. Two years earlier, he had taken out a $2,889 loan from his mother, and an annual installment payment was due soon. However, he intended to pay less than what was expected. The disagreement didn’t help the poor relationships Frank already had with his family, who considered Susan and her relatives high-flown. Gustave once fired his revolver over the heads of Susan and her brother as they were crossing a field — just for fun, he later explained.

On the day before the murders, Frank went to the bank, then stopped for a beer at a nearby saloon. He planned to pay his taxes and had as much as $400 on his person. Someone may have followed Frank home, Stellwagen reasoned, then waited until nightfall to enter the house. Or perhaps it was a random break-in. Tramps were a menace in the countryside, accounting for numerous thefts and the occasional rape or murder. Frank, not known to own a gun, had on at least one occasion mentioned getting one to deal with them.

The revolver pulled from the rubble was too damaged to be traced to its owner. If it was Frank’s, it would lend credence to an alternative theory offered by Dr. Felix Fettig, the Knochs’ family physician. He firmly believed the massacre was the result of the couple’s ongoing differences over religion, an issue other witnesses mentioned. Frank was a Protestant but Susan was committed to raising the boys as Catholics. Fettig theorized that, following an argument, Frank had impulsively killed his family, set the house on fire, and then shot himself. Many dismissed the murder-suicide scenario as an unlikely act of madness — but, as the Free Press noted, “It is quite well-established that insanity is hereditary in the family.”

Frank’s grandfather, Fred Knoch, a German immigrant who worked as a butcher, suffered from mental illness. Two of Fred’s children (Frank’s aunt and uncle) also were institutionalized. In fact, in the immediate aftermath of the murders, it was feared that the uncle had escaped and committed the deed. Frank’s father, Christian, was the third of Fred’s offspring to suffer from dementia, although his condition apparently was milder. At the time, there was no sophisticated treatment of the mentally ill. People suffering from conditions now recognized as schizophrenia, manic depression, and other psychiatric and behavioral disorders were lumped together in the broad category of “lunatics.” Most were tolerated, ignored, or ridiculed until they became too troublesome to society, at which point they were shipped off to the hell of an asylum.

Christian and Elizabeth Knoch brought up eight children on their Springwells farm. Charles was the oldest of their four sons, followed by Frank, Gustave, and Herman. One day in August 1879, Christian was working in the barn when, according to Elizabeth, he was kicked in the head by a horse — twice. Despite the two pulverizing blows, the 54-year-old farmer was able to crawl into the house and tell her what had happened. He died the following day without uttering another word. Blood was found on the barn floor, but the story didn’t sound right to everyone. “My father’s injuries were on the top of his head,” Herman said. “I should think one would have to get down to be kicked in that place.” Christian’s death was ruled an accident and he was buried at Woodmere. Charles, now in charge of the farm, paid $36 for the 12-by-12-foot family plot in Section D, situated halfway between the cemetery’s main entrance and Baby Creek. (The creek was dredged in 1967 and is now Riverside Drive.)

On the morning of Nov. 11, 1882, Charles vanished. Neighbors would later remark that the family seemed largely unconcerned by his absence. The following spring, his body was found in the Detroit River. He had been shot in the right temple and his body weighed down. A coroner’s inquest determined that the pump chain found wrapped around his neck and the copper wire attached to his coat came from the Knoch farm. Gustave testified that he had gone to the markets in Detroit on the day his brother disappeared, returning home at midnight to find the rest of the family in bed. The next day, he produced $100 that he said Charles had left behind in a tin box in the greenhouse.

Years later, Gustave would say that he always believed Charles had killed their father in an argument and that their mother had covered up the crime. According to Gustave, Charles lived with his guilt for three years until one day, he wrapped himself with a chain and weight, stood on the edge of a dock, and shot himself before toppling into the river. This seemed a rather elaborate suicide. A more plausible scenario had the 24-year-old bachelor, his pocket stuffed with money, being waylaid en route to enjoying a Saturday in Detroit. A farmhand said that on the day before Charles disappeared, he noticed two strangers sitting on a nearby fence, speaking in a language he couldn’t understand. He called Charles’ attention to the men, but by the time he and Charles went to investigate, the strangers were gone. Authorities ultimately judged the death a homicide, although nobody was ever arrested.

The deaths of Christian and Charles were revisited as the inquest into the Springwells massacre continued through the 1885 holiday season. The demeanor of the Knochs on and off the witness stand aroused suspicion. They seemed cold, indifferent, although some in Spring-wells said that was their natural mien. Herman admitted that his reaction to frantic shouts that Frank’s house was ablaze was to go back to bed. One witness described how Gustave had visited the site of the tragedy the following day and flippantly remarked, “Well, they’re gone.” Elizabeth, who testified that her sons were at home the night of the fire, laughed at inappropriate times, which drew a rebuke from the prosecutor.

However, the ordeal was exacting a toll from the family matriarch. When saloonkeeper and family friend Eli Unruh visited Elizabeth the day after Christmas, she was visibly distraught. “I have nothing to say now; when I try to say a word they tell me to shut my mouth,” she said, referring to her children. She took to her bed, complaining of stomach and head pains. On the afternoon of Dec. 31, Stellwagen learned of rumors that the ailing woman wanted to make a statement, possibly a confession. The sheriff and prosecuting attorney went to her home the next day, only to be told that they were too late. Elizabeth had slipped into a coma on New Year’s Eve and died in the wee hours of 1886.

Authorities suspected the 61-year-old woman was poisoned. As was the custom then, the deceased was laid out in her coffin at home. On the evening of Jan. 2, the county physician conducted an autopsy by lamplight in the living room. Dr. Owen was surprised to discover a skull fracture that extended from one temple to the other. There had been no bruising or other external signs of trauma, which might indicate a recent accidental fall. He theorized that Elizabeth had been struck on the side of the head with a heavy bag of sand, a blow designed to kill while leaving no visible mark. “The Mother Murdered!” newspapers declared. “The Seventh Tragic Death in the Knoch Family.” The inquest into the Springwells massacre was put on hold to deal with this jolting turn. Prosecutors ordered a new autopsy, this time with Owen being joined by three other doctors, including Elizabeth’s physician. Meanwhile, Herman and Gustave were arrested and locked up inside separate 5-by-7-foot cells at the county jail on Clinton Street.

Feelings were running high. D.J. Campau, a well-fixed landowner who had conducted business with the Knochs for years, came to the family’s defense, paying for all legal and medical representation. “I have known these boys for a long time as honest, industrious and frugal,” he explained. “In the excited condition of the public mind they were liable to be unfairly dealt with and having the utmost confidence in them I propose to stand by them to the last.”

The second autopsy was performed Jan. 4 at Woodmere and produced an entirely different verdict. The new team of examiners decided that Elizabeth had not been poisoned or murdered, but had most likely died of inflammation of the brain brought on by pneumonia. Owen stood by his belief of foul play, bristling when it was suggested that he had inadvertently created a post-mortem fracture while chiseling off the skullcap during the original autopsy. Afterward, the deceased was interred without her head, which was kept at a doctor’s office in case further examination was required.

Having been whipped into a state of near-hysteria by rampant rumor peddling and dueling press reports, not everyone readily accepted the revised finding. Stellwagen, worried about a possible lynching, kept the Knoch brothers locked up until the day after the funeral. Upon their release, Campau expressed his fear that Herman, sporting a strange fixed smile and a piercing look in his eyes, had been “affected by the excitement” and “might sustain another attack.” Gustave said he would watch after him.

Owen’s theory that Elizabeth had not died a natural death found support with the boys’ uncle, John Knoch, who was Christian’s brother. Most evenings, John could be found inside some saloon, freely voicing his opinions. Gustave and Herman had killed Frank, their mother, the whole family, he said. Gustave warned him to watch his tongue, or he’d report him to authorities.

On Jan. 21, the coroner’s jury released its verdict. Frank and his family had been murdered “by persons unknown.” Those persons remained unknown as rumors continued to fly. In early February, a laborer discovered a bloodstained vest and trousers near Frank’s farm, prompting newspapers and gossipers to rush a new round of speculation into circulation. No link between the clothing and the murders was found. Meanwhile, law-enforcement agencies far and wide continued to keep a lookout for the Knochs’ missing hired hand. Since the murders, a dozen different “Alecks” had been detained and released.

On March 7, a Detroiter named Govinski approached Stellwagen and said he knew of the real Aleck’s whereabouts. The suspect had drifted through several jobs since leaving the Knochs and was now working at a foundry in Hamtramck. Aleck was arrested at a boardinghouse on St. Antoine and interrogated. Described as “a big lump of humanity,” he struggled to comprehend the brutality described to him through a translator. “All dead?” he asked in disbelief. Stellwagen ended the interview. “He is an ignorant Polander,” The New York Times concluded, “and evidently knew nothing of the murder.”

With nobody in custody, the public was jumpy. Stellwagen was obsessed with the case, spending long hours and a chunk of his own money in an attempt to solve it. Recognizing the limitations of his understaffed department and his own ordinary investigative skills, he personally retained the services of a private detective. Citizens were not optimistic, despite the posting of a $1,000 reward. The general opinion in Springwells, observed one Detroit daily, “is that the present generation will not see the mystery solved and that further investigation will be fruitless.”

In July 1886, Stellwagen received word that two crooks serving time at the state prison in Jackson had incriminating information about a man named William Horrigan. Con Kane, recently sentenced to 10 years for safe-blowing, and Charles “Kid” Smith, a “gentleman thief” who had just gotten six years for stealing a batch of suspenders, were willing to testify that, in September 1885, they had been approached by Horrigan to “do up” a local farmer who was known to keep a lot of cash at home. It would be an easy job, Horrigan allegedly told them, but they declined. Now, seven months after the quadruple murder, they decided to come forward with what they knew.

Although Stellwagen hinted of circumstantial evidence tying Horrigan to the crime — evidence that apparently never was produced — any case brought to trial clearly would hinge on the credible testimony of Kane and Smith. The sheriff had misgivings about their story; there were always convicts willing to perjure themselves for ulterior motives. Nonetheless, Horrigan was located, arrested, and taken to the county jail to await a pretrial examination. Two weeks later, Kane and Smith were delivered in handcuffs. Early on Aug. 7, just before the start of the hearing, Stellwagen brought the pair into his office separately to identify the suspect. Kane was first. “All right then,” Stellwagen said, “is Horrigan the man or not?”

Kane eyed the suspect, then asked to hear him speak. “He looks just like the man,” he said, “but he is an inch shorter than the one who spoke to us.” Smith was ushered in next. He barely looked at Horrigan before saying he did not recognize him. Stellwagen was frustrated but not surprised. Upon his recommendation, the prosecutor immediately asked the court to release Horrigan — a decision that disappointed the large number of people who had made the six-mile trip from Springwells on a Saturday morning to catch a glimpse of the Knochs’ purported executioner.

Stellwagen’s suspicions about the accusers soon proved correct. Two days later, Kane and Smith were being returned to Jackson in the care of a prison turnkey when they made a break for it at the Michigan Central Depot, with Kane brandishing a revolver that had been slipped to him by an outside accomplice. Their escape was thwarted by the actions of a quick-thinking porter, who “knocked the pistol out of Kane’s hand and caught him by the throat, choking him until his tongue protruded from his mouth,” the Free Press reported.

Few doubted that Horrigan was capable of breaking into an isolated farmhouse at night, especially after he was sentenced in October to five years in prison for the after-hours burglary of a Detroit shoe store. But could a practiced thief, whose self-composure during weeks in custody had been favorably noted by the press, mutate into the kind of monster capable of the atrocities committed upon the Knochs? “You never hear of a professional thief or burglar committing murder unless he is ‘pinched,’ and then they only kill enough to save themselves,” ex-detective James McGuire told the press. McGuire’s theory was that an amateurish “bungler” had been detected by Frank or Susan Knoch, at which point the startled intruder “committed murder, and to cover up the first murder he killed three more people.”

The Horrigan fiasco was the last significant event of the Knoch family murder investigation, though Stellwagen doggedly kept at it. “I may not meet with success,” he said, “but when I retire from office I will have the consciousness of knowing that I did what the people expected of me.” Despite the sheriff’s best efforts, the case was at a standstill when his term expired in 1887.

The widespread fear engendered by the murders gradually dissipated. In August 1892, seven years after the massacre, authorities arrested Herman Knoch for assaulting a Springwells resident named William Roeser. Under the headline, “A Raving Maniac,” the Free Press described the “desperate resistance” Knoch put up before finally being overpowered inside a barn and taken to jail: “While being registered he became very violent, and it required the combined efforts of five deputies to place him in a cell. When Deputy Sheriff Hayes brought him some bread, Knoch hurled the dishes against the sides of the cell. The probate court sentenced Herman to the state asylum in Pontiac. He spent the rest of his life there, dying in 1911 from what the coroner described as “exhaustion from insanity.”

Meanwhile, Gustave Knoch married a 16-year-old Detroit girl named Minnie, and together they reared eight children to adulthood. For many years, Gustave operated a successful flower shop on Fort Street, near the cemetery’s entrance. One winter day in 1917, the 53-year-old florist went into the boiler room behind the greenhouse and hanged himself. Like Herman, Gustave was buried in a separate plot at Woodmere, taking with him whatever secrets he may have held about the family deaths that had preceded his.

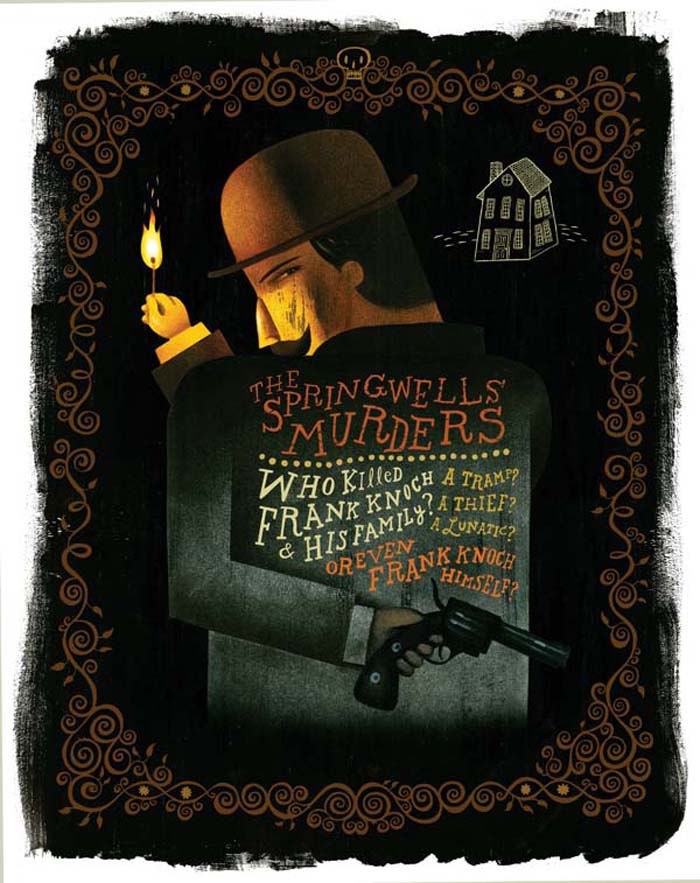

Stellwagen moved on to other challenges after leaving office. He helped organize a bank and a general store, became the president of a carriage factory, and made a good deal of money. Upon his death on Aug. 13, 1904, he was eulogized as being “successful in all his work.” But open questions had pestered the erstwhile sheriff. Who was responsible for the Springwells massacre: a tramp, a thief, a lunatic, or even Frank Knoch himself? Were Gustave and Herman, either individually or jointly, complicit in the murders, or in any of the other family deaths? Could the deaths of the parents, Christian and Elizabeth, really have been homicides? Could the murders of the brothers, Charles and Frank, actually have been suicides? Or was the string of tangled tragedies the work of outside forces, a cruel cosmic joke played on an unhinged but unfathomably luckless family? The multitude of theories kept tongues wagging in Springwells for years.

There was a grim postscript to Stellwagen’s passing, as if the dementia associated with the Knochs had somehow infected his own bloodline. On Thanksgiving morning in 1905, his nephew and namesake walked into a parlor and, in front of family members, ran a razor across his throat. There was no satisfactory explanation for young George Stellwagen’s suicide. Perhaps none could be expected. As a forsaken plot in Woodmere suggests, what is life but madness?

If you enjoy the monthly content in Hour Detroit, “Like” us on Facebook and/or follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates.

|

|

|