Metro Detroit has had its share of memorable amusement parks, including Edgewater Park, Jefferson Beach, Eastwood Park, and Walled Lake. But the granddaddy of them all was Bob-Lo, the oasis of leisure in the Detroit River, just west of Amherstburg, Ontario

Metro Detroit has had its share of memorable amusement parks, including Edgewater Park, Jefferson Beach, Eastwood Park, and Walled Lake. But the granddaddy of them all was Bob-Lo, the oasis of leisure in the Detroit River, just west of Amherstburg, Ontario

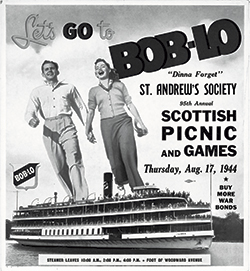

Scads of Detroiters remember piling on the Columbia or Ste. Claire on a downy summer day, taking in the cool river breezes, and disembarking on the island for a day of fun. Others will warmly recall the moonlight cruises, dancing under a star-pocked sky to the strains of Joe Vitale’s band. It was only an hour away by boat, but Bob-Lo seemed light years removed from the hubbub of the steamy city.

The history of the island is told in Patrick Livingston’s solidly researched Summer Dreams: The Story of Bob-Lo Island (Wayne State University Press, $24.95). It’s chock-full of historical tidbits, and is enlivened by reminiscences from people who were employees on the island.

And what history of Bob-Lo would be complete without a profile of Joe Short (aka Captain Bob-Lo), the appropriately named diminutive fellow who used to greet children as they boarded the boats. Short had been a clown with the Ringling Bros. Circus when he was hired in 1955, and he used to work as one of Santa’s elves at Kern’s and Hudson’s in the off-season. Short would also kick up his heels to “Anchors Aweigh” each time the boat set sail.

Although pleasure-seekers had been ferried to the island since 1898, Bob-Lo didn’t become a full-fledged amusement park until 1949. It had some rides before then, but people went there primarily for picnics, swimming, bicycling, roller-skating, taking a whirl on the carousel, and dancing.

Most memories of Bob-Lo are happy ones, but if you were African-American of a certain age, the recollections could be stinging. Livingston recounts a story from former Mayor Coleman Young, who as an eighth-grader was denied boarding when an employee yanked off his cap, saw his curly hair, and informed him that black children weren’t permitted on the island. Ironically, Bob-Lo had once served as a stopover for escaping slaves on their way to freedom in mainland Canada.

More recent times were marred by rowdy gangs. On Memorial Day of 1988, the Coast Guard had to be summoned because the crew was concerned that the tilting Columbia (caused by the weight of frightened passengers taking cover from fighting gangs on the other side of the boat) might capsize.

The last excursion was in 1993, and today the island is residential, the rides gone. But Livingston’s book serves as a boarding pass to a time when Bob-Lo thrived.

|

|

|