We may think our national borders are porous today, but they were virtual sieves in April 1942. Four months after Japanese planes pummeled Pearl Harbor, a sworn enemy of the United States easily slipped into Detroit.

We may think our national borders are porous today, but they were virtual sieves in April 1942. Four months after Japanese planes pummeled Pearl Harbor, a sworn enemy of the United States easily slipped into Detroit.

Lt. Hans Peter Krug, a 22-year-old Luftwaffe pilot whose plane was shot down in the Battle of Britain, escaped from a POW camp in Bowmanville, Ontario, and either stole or was given a boat from a German-born woman who lived near Windsor. From there, Krug paddled to Belle Isle and crossed the bridge. What happened next gained national, even international, attention.

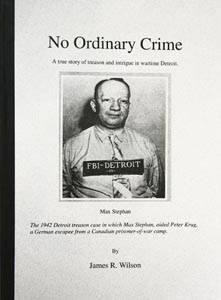

However, it wasn’t Krug who was in the spotlight so much as pudgy, German-born Max Stephan, who ran a restaurant on East Jefferson and Grand Boulevard with his wife, Agnes. Stephan fed Krug, took him out for drinks, and even paid for the younger man’s visit to a brothel. He arranged for Krug to stay at a nearby hotel and, the next day, drove him to the Greyhound station downtown. He supplied Krug with money for a bus ticket to Chicago, from where the lieutenant planned to head to Mexico, South America, and back to Germany. He was arrested by the FBI in San Antonio.

Before he met Stephan, Krug arrived at the east-side flat of Margareta Bertelmann, a German immigrant whose address Krug remembered from packages she sent to POWs in the Canadian camp. She also supplied him with money and clothing.

Stephan was charged with treason, convicted, and sentenced to hang. Bertelmann couldn’t be charged with treason because she wasn’t an American citizen, and was sent to an enemy alien camp in Texas.

Although Michigan had long abolished the death penalty, this was a federal crime. The case was a sensation, in no small part because this was only the second time in U.S. history in which the defendant was sentenced to die for treason. The first was during the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s, but the two convicted men were pardoned by President George Washington.

Eight hours before he was scheduled to swing, Stephan received clemency, too. President Franklin D. Roosevelt commuted his sentence to life in prison, which is where Stephan died of bowel cancer in 1952.

The case is told in fascinating detail in James R. Wilson’s No Ordinary Crime (self-published, $14.95). The book was originally published in 1989, but Wilson, who lives in Bellaire, Mich., has added additional information and photos in the new version.

Wilson’s volume teems with local color and captures the fear of the time. In 1942, it was by no means clear that the Allies would win.

Wilson implies that Stephan, although sympathetic to the Vaterland, was not a virulent Nazi. Nor, for that matter, was Bertelmann. They were likely more guilty of stupidity than treason. But Stephan was friends with a nasty anti-Semitic shop owner, one Theodore Donay. Stephan brought Krug to the store, and a clerk overheard Krug talking about his escape and notified the authorities.

Krug’s boundless arrogance became apparent when he agreed to be questioned at Stephan’s trial. He appeared before a shocked court in full Nazi regalia, even giving the Nazi salute to a stunned bailiff. He parried many questions, but he implicated both Mrs. Bertelmann and Max. Privately, Krug thought Max a dummkopf, and he regarded all Americans in a similar light.

While Wilson’s research is solid, his book is somewhat weakened by biased statements, such as: “Roosevelt deserves full credit for a just and humane decision.” Readers should be left to draw their own conclusions. The book also needs a good copy editor.

Still, No Ordinary Crime is an engaging story, made all the more gripping because it’s true.

To buy: Horizon Books, Traverse City and Petoskey, or Round Lake Bookstore, Charlevoix.

|

|

|