Detroit has earned international attention for its urban farming — vacant lots converted into beautiful, green vegetable gardens set amid burned-out neighborhoods. Greening of Detroit, a nonprofit environmental group, claims that 15,000 people in Detroit call themselves urban farmers. But this is not the first time Detroit turned to farming to address an urgent need.

A financial panic in 1893 was nationwide, and the economic depression that followed had a severe effect on Detroit’s banking and business sectors. Manufacturers closed up or laid off workers to the point that unemployment rose to 43 percent. Especially hard hit were the foreign born, Polish and Germans, who were more than 50 percent unemployed and drew “pauper relief” from the city’s Poverty Commission. The results were felt on Detroit streets.

A Polish mob forced a street repair gang to throw down their shovels and give them a chance at work. Police faced the mob down with clubs and drawn revolvers. The Detroit Tribune quoted a Dr. W.C. Kwiecinski who attacked Italian-Americans, claiming, “They get all the work over the city… . An Italian can live on black bread and onions, whereas a Pole must have good food.”

Another 500 Polish men armed with shovels confronted Sheriff C.P. Collins, and two deputies who emptied their revolvers into the charging mob but were overwhelmed as shovels came down on them and beat them into a “senseless bloody mass.”

Ethnic groups turned against each other. The Michigan Catholic asked for “severe punishment against a savage mob of howling Poles.”

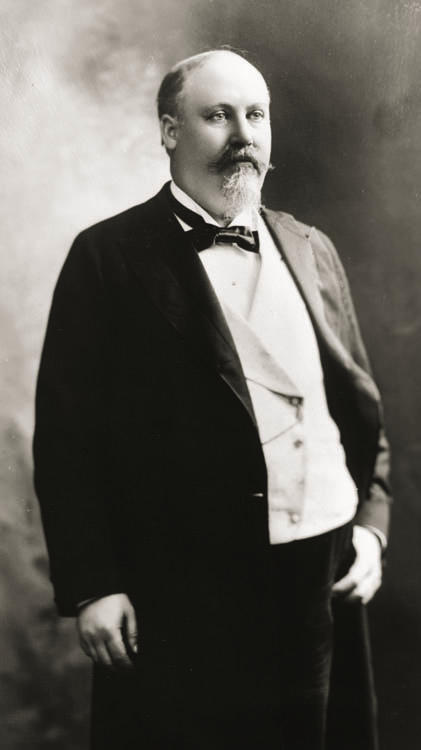

In the center of this storm was Detroit’s outspoken and progressive mayor, Hazen S. Pingree.

In December of 1893 he formed a committee to find solutions to help these thousands of desperate, some starving, people. He also hoped to avoid the violent confrontations that were occurring in Detroit and across the country.

Pingree invited manufacturing leaders, including George H. Barbour of Michigan Car Company, board members of public utilities, and city aldermen, but also invited labor representatives such as Sam Goldwater, head of the Michigan Trades Council.

It was winter and available unskilled jobs were scarce. One committee member suggested cutting timber on Belle Isle; another said they might saw cedar stumps used for street paving.

Through this meeting Sam Goldwater repeatedly insisted that these men needed to work for their money. They would not take humiliating handouts from the Poverty Commission. He referred to it as “the stigma of pauperism.” Pingree listened and thanked Goldwater for his advice.

To start, Pingree applied pressure to bakeries to reduce the price of bread, which at that time sold for a nickel a loaf. He eliminated trucks at work sites to allow for the hiring of men to haul stone by wheelbarrow. Some unemployed dug trenches for pipe.

But it was in June of 1894 that Pingree initiated his original idea of turning vacant land into garden plots. At that time (as is today) Detroit had a lot of empty space; owners and syndicate investors sat on open land waiting for prices to rise.

Since many of the foreign emigrants were not long removed from peasant farms, Pingree believed they might take to raising their own food.

In the summer of 1894, Pingree convened another meeting. He invited an adviser named Captain Cornelius Gardener, who was with the 19th Infantry stationed at Fort Wayne. Gardener was from Holland, Mich., a West Point graduate, and shared many of Pingree’s beliefs. Pingree regarded Gardener as an honest, compassionate man, but above all, a strong executive in whom he could depend to see the project through.

Pingree and his causes were loudly vilified by many. Every Detroit newspaper came out against the urban farm idea. He did not need to bring a firestorm of ridicule onto his head through incompetent management. Gardener agreed to take on the program.

Pingree was a big, stocky man who grew up on a farm in Maine but made his fortune by manufacturing shoes. He knew nothing about farming so during the meeting he placed a telephone call to a friend, James M. Turner, in Lansing, as captured in the Detroit Free Press on June 10, 1894:

“ ‘Say, Turner’, yelled the mayor. ‘How many teams will it take to plow a thousand acres in a day? Teams! Teams! Yes. Get that? Well, I can hear you right well. What’s that? Alright. One thousand acres. Okay. Wait! Alright, one team can plow two acres a day.’ Aside to others in Mayor’s office — ‘Great farmer that Turner- knows all about it.’

‘Say, Turner, how many potatoes does it take to seed an acre? Potatoes! Potatoes! Yes, how many to seed an acre? What? Seven bushels. S-e-v-e-n. Seven. All right.’ ”

He went on with beans, turnips, and more.

A reporter at the time, John Lodge, who would become mayor in the 1920s, characterized Pingree as no intellectual. He dealt with one idea at a time, but on that one idea he would become passionate in his cause. As Lodge frequently wrote, “His blood was up.” He was always shouting. His bald head beaded with sweat; he was so loud and profane that frequently police guards rushed in to see if something had happened.

Pingree went public in his call for the acreage; Gardener went to secure it, making sure “unsightly farms” would not be near upscale neighborhoods. The Poverty Commission’s funds were exhausted, so Pingree took his idea to the churches to raise money for tools and seed.

“Most of the unfortunate would be glad to raise their own food,” Pingree argued. “They are willing to work, and we ought to give them a chance to do it.”

As expected, the big churches treated the idea with sarcasm and contempt; he raised an insulting $13.80 total from the churches. Soon after Pingree advocated repealing the churches’ tax-exempt status.

The Detroit Evening News printed a cartoon depicting Pingree as a despot named “Tubor I” holding a carrot as a scepter and in the other hand a potato.

He approached the city’s wealthy elite, men with whom he once socialized, and some of whom were friends. They turned Pingree away; the shared belief was that “these people” were naturally lazy, which explained why they were out of work.

This hit hard. Pingree saw this as betrayal, both to himself but more so to the poor, the people who elected him. Detroit’s elite were made wealthy by the hard labor of these people, Pingree felt, and now in their desperation the wealthy offered nothing.

Undeterred, Pingree sold his prize horse at one third of its worth to kick off the potato patch program, and got access to farm 430 acres of land owned by the city. It was called a publicity stunt by his enemies — which it was.

In mid-June when the program seemed ready, City Hall opened to begin signing up people. Pingree arrived and placed his chair right beside the entrance door of the Common Council chamber. George Barbour soon showed up, as did Captain Gardener and the staff.

It was quiet. No signups arrived.

Pingree told them not to worry. But they were beginning to seriously worry; it was getting late in the summer and the only crops that garden farmers could plant by this time was “late potatoes.”

Finally, Pingree got up and walked down to the building entrance. There he saw a small group of Polish people waiting outside the door hesitantly. He waved them inside, shouting, “All right, come in! Come on! Don’t be afraid. Come on in.”

Very quickly, 3,000 families applied to work plots, but there was only budget for 945. In a report titled On the Cultivation of Idle Land by the Poor and Unemployed, 1895, Prepared by Capt. C. Gardener, Gardener wrote that in the first year, the plan yielded 65,000 bushels of potatoes, and despite the late planting they planted and harvested pumpkins, radishes, cabbage, lettuce, beans, turnips, corn, and squash. The produce had a cash value of $14,000.

Hoping to show off the success, Gardener took samples to retailers but grocers refused to sell or display any of the prize specimens for fear the wealthy customers would boycott their stores.

In 1895 enrollment for farm plots grew to 1,500 and in 1896 to more than 1,700; Pingree said people were fighting to get into the program. The value of their harvest had grown to $30,998, more than the outlay of the city Poverty Commission.

It had succeeded beyond anyone’s dreams. Pingree became a national hero. The “Detroit Plan” as it was called across the U.S. was copied in other cities such as New York, Boston, Pittsburgh, Duluth, Chicago, Minneapolis, Seattle, and Denver. Overseas, Berlin, Germany, also developed “Pingree Patches” on open land in 1915.

Pingree was unquestionably proud of the program, and took no small satisfaction in proving the “croakers” wrong. The cover page of his book, Facts and Opinions, has a full-page print of a giant potato. However, for Pingree himself, his concept of social justice became keener, more discerning, yet more cynical and vindictive; he doubted the long-term effectiveness of charity. In 1896 he told the Terre Haute Benevolent Society: “Charity, in short, is the handmaid of economic oppression.”

|

|

|