Detroit’s Palmer Park is “tired,” in the words of Robert Gibbs. A decade ago, in fact, it was so little used that the city briefly closed it for lack of budget to maintain it. But, Gibbs long wondered, could the moribund, 296-acre green space along Woodward Avenue be a gem hidden in plain sight — a landscape version of the fabled Picasso in the attic?

Rumors about the park’s initial design led to a 2014 review of Library of Congress records by Gibbs, a Birmingham-based landscape architect involved with a far-reaching renovation of the park, that confirmed a remarkable fact: There really was a long-forgotten, hand-sketched design for part of Palmer Park from the late 1800s penned by the legendary green space pioneer Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.

If you’ve enjoyed the green spaces of just about any urban setting in America, you have Frederick to thank. Olmsted’s unparalleled portfolio includes a slate of iconic American green spaces, including New York City’s Central Park and the U.S. Capitol grounds. “It was fascinating that nobody in the area or nationally knew that he was involved in [Palmer Park],” Gibbs says. “This is quite a find. … It’s very rare to have an original senior Olmsted park.”

Gibbs believes leaning into the Olmsted history is important. “Detroit hasn’t been a city that saves and preserves its historic buildings and cultures,” he says. “This will help encourage people and institutions to restore historic buildings rather than tear them down.”

Indeed, Olmsted’s original plans are now central to the restoration efforts of the local group People for Palmer Park. And that, some experts say, might well be a smart way to enhance the attraction’s cache — as long as they don’t overdo it. “This is an excellent start, but Palmer Park is a landscape of a layered history, and that layered history needs to be understood when managing change today,” says Charles A. Birnbaum, founder of The Cultural Landscape Foundation, a nonprofit that educates the public about green space preservation. “Olmsted is part of a continuum. It’s part of a story that we continue to be able to reveal today, so we can understand how to manage this landscape in the future.”

Urban green spaces evolve with the cities that surround them. And while Olmsted’s imprint on Palmer Park was confirmed, the park has always been a sum of more than just what Olmsted envisioned. Even its heart, the Merrill Plaisance, was an idea of Olmsted and design partner Charles Eliot. “Your estate will, we feel for sure, possess no rival in Michigan so far as beauty and general attractiveness are concerned,” Olmsted wrote to the park’s namesake, Sen. Thomas Witherell Palmer, in 1895 when he proposed the large central green space and a wooded knoll that became the Witherell Woods.

In addition, though, the adjacent Palmer Woods Historic District was designed by Ossian Simonds, a founding member of the American Society of Landscape Architects. And other designers made their own contributions to the landscape, which includes a public golf course, during the 1900s.

People for Palmer Park President Rochelle Lento says the master restoration, which is about one-third complete, aims to “make sure that anything we do respects the integrity of how the park was laid out and what the original design was, particularly with the way the streets are curved and the green space and natural elements like the lake that’s to the south end of the park,” Lento says. “We’ve just tried to honor the existing design.”

Among the projects undertaken so far: An ornamental lighthouse is being refurbished for $55,000, and renovations to the playground and a 135-year-old log cabin that was once a summer refuge for the Palmer family have taken place in recent years. The group also has a $300,000 grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to restore the natural habitats of Lake Frances and Witherell Woods, work that is ongoing.

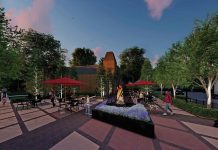

Future goals include restoring the park’s long-shuttered Merrill Fountain, repairing native landscaping, and even adding outdoor cafes, according to the master plan. A historic band shell is expected to be moved to Palmer Park soon from the old State Fairgrounds, where it served as a stage for the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington.

Birnbaum is impressed by the local enthusiasm for restoring the park. Since People for Palmer Park was formally established in 2011, the group has raised money, personally worked the land, and pressed the city to bring the property back to its past glory.

“To see such an engaged grassroots community of engagement, it’s the best of all worlds,” Birnbaum says, noting another way that the Olmsted connection can bolster the effort. “The more discoveries that are made that are shared with the community, the more empowering it is. We need to understand where we come from to understand where we’re going.”

This story is featured in the October 2021 issue of Hour Detroit magazine. Read more stories in our digital edition.

|

|

|