When Michael VanOverbeke purchased the one-time H.P. Pulling House, his first property in Detroit’s Brush Park, in 1993, reaction was less than positive. “Others thought I was crazy,” he claims.

He wasn’t deterred. “I’ve always flown under the radar a bit,” the attorney and former restaurateur says. Among the city’s early investors in the downtown core’s revitalization, he is quick to credit urban pioneers who came before him, some of whom he met when he owned On Stage restaurant and bar in Grand Circus Park and who planted the seeds of his eventual purchase.

Centered between the medical center, downtown, and Midtown, Brush Park is one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods. It dates back to the 1860s and was once home to notable Detroiters Albert Kahn and Joseph L. Hudson. By the 1920s, once most of the area’s houses had been converted into rooming houses for automobile plant workers; it later become a thriving Black neighborhood.

VanOverbeke fell in love with the area’s legacy and developed a hunch that someday, others might, too — and the neighborhood would be ripe for revival. He was right. After restoring four historic structures, he’s now taking on his latest — and probably his most ambitious — project yet, a mixed-use development he calls Coda, named after the musical term meaning finale or conclusion. Incorporating a one-time carriage house at the corner of John R and Alfred next door to his current office, Coda is the culmination of a longtime dream to bring the 19th-century building back to life.

He bought the H.P. Pulling House on a land contract and, in the beginning, rented it out. He didn’t start renovating for eight to 10 years, a period during which he said surrounding buildings were broken into and a nearby crack house burned to the ground.

VanOverbeke went on to buy and restore three other historic structures — the Hudson-Evans house in 1999; the former Lucien Moore estate, purchased with a business partner in 2011, developed and later sold; and the Mount Sinai Grand Lodge in 2015, which operated as a Black Masonic lodge from 1921 to 1943. “During the city’s historic bankruptcy, this home with the Renaissance Center in the background was frequently used as a demonstration of the decay in the city,” he says.

The Wayne State University and Detroit College of Law grad had always envisioned his law firm in a big old Victorian home. Purchasing the Evans-Hudson house with his law partners in 1999 helped make that vision reality. Built by David Whitney Jr. in 1872 as a wedding gift for his daughter, Grace, it later became home to J.L. Hudson. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Luckily for VanOverbeke and the neighborhood, the house had never been stripped. The 7,800-square-foot French Renaissance revival home boasts 14-foot ceilings, six original fireplaces, detailed plaster and woodwork — including a gorgeous winding staircase and banister leading to the third-floor bedrooms — and an original stained glass window. Even after more than two decades, VanOverbeke still enjoys going to work; his favorite view is from the base of the stairwell, looking up.

Those sights, he says, will change when he gets to work on Coda.

He credits Maurice Cox — the city’s director of planning and development from 2015 to 2019 — with changing the face of Brush Park redevelopment and making contemporary projects like Coda possible. Previous administrations had limited new projects to faux-Victorian structures, he says. Cox was the first to see that the two styles could complement each other, he says.

Even within that context Coda is unusual, he says. Once on the demolition list, the carriage house has been vacant since it served as a pottery studio and caught fire 15 years ago. VanOverbeke watched the property for years before it became available in 2016.

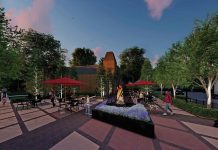

Plans include bracing the historic structure and building a five-story contemporary building over it. Expected to break ground this summer, the project has already received an AIA Design Award. It will ultimately include 10 condominiums, a two-level restaurant, office space, and a parking structure. It is also the first building in Detroit to use mass cross-laminated timber for its load-bearing structure, a practice promoted by a variety of conservation organizations. “I’m building something that hasn’t been done in Detroit yet,” VanOverbeke says.

What attracts him, besides the craftsmanship and workmanship of the historic structures, is “the feeling that you’re part of that neighborhood’s history,” he says. “The idea of those things getting lost in time is a crime.”

He hasn’t regretted his purchases or the work the structures have required. Thirty years later, changes to Brush Park are “like night and day,” he says. Reactions to his investments in the area have also changed. Some say he is a great visionary, he says, while others say

he got lucky. “The reality,” he says with a laugh, “is somewhere in

the middle.”

Learn more about Coda at codadetroit.com.

This story is from the July 2022 issue of Hour Detroit magazine. Read more stories in our digital edition.

|

|

|