Ford executives, casting about for a firm to oversee a master plan for redeveloping Michigan Central Station and the 30-acre area around it, landed on a New York firm called Practice for Architecture and Urbanism, or PAU.

Its founder, Vishaan Chakrabarti, 56, has focused his career on large-scale urban revival efforts. Notably, he helped concoct the groundbreaking idea of repurposing an elevated freight rail line in Manhattan as a public park known as the High Line; PAU is currently designing the expansion of Cleveland’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Chakrabarti, who was born in Kolkata, India, and arrived in the U.S. at age 2 with his family, first came to Detroit on a mid-1990s cross-country road trip with his girlfriend in a 1983 Honda Civic. They went to a downtown jazz club, he says, and became charmed by the city. Decades later, he’s at the center of the process of revitalizing it, as he explains to Hour Detroit.

How did you get involved with the Michigan Central project?

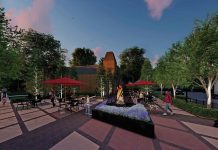

I spent a fair amount of time in Detroit. I really love the city. And [Ford executive] Mary Culler’s office called me, probably coming on five years ago now, saying they really need help with master planning and creating a sense of place around Michigan Central Station. They wanted help understanding how to make this a place of innovation and mobility and how to create a sense of public glue. It’s about the buildings, but it’s also about the space between the buildings and how to create an invitation to the station, The Book Depository, Roosevelt Park, and the entire surrounding neighborhood.

For years, people talked about demolishing the train station. Why would that have been a bad idea?

It’s an extraordinary building in terms of its architectural integrity. There are many spaces throughout that building that are unique and special that you would never build in a new building today because of labor costs. And at different points, Michigan Central has represented the heyday of Detroit and the lowest points of Detroit’s history when it became nothing but a ruin filled with graffiti. Now I think it’s about the city’s rebirth.

Would the city be renovating Roosevelt Park if not for the Ford project?

What happens is investments build upon investments and ambition builds upon ambition. And so when Ford announced that they would be a lead player renovating the station to make this a real locus of activity in Detroit, that probably helped to catalyze the city’s decision to put money into Roosevelt Park. This isn’t going to be all about Ford. Ford is the gardener here, and they’re planting seeds. A lot of other flowers will bloom as a consequence of Ford’s initial actions.

You’ve spoken about a “360-degree perspective” on Michigan Central. What does that mean?

The station was originally designed to have a front and a back — the Michigan Avenue side and the platform side. Today, we want to think about that more holistically. Sure, the Michigan Avenue side is super important, but so is the Mexicantown side. People from Mexicantown historically were fenced off from the station. Now there is no front and back. The people from Mexicantown will have a real sense of invitation. A lot of our work was around saying, “OK, if you have the station as a magnet and it’s 360 degrees, what’s the network of public spaces around it?” How do we make it so other players come into the area and say, “This is a great place. I want to do everything from renovating a two-story brownstone to building a new academic building.”

How does Michigan Central fit into the themes of your career?

We’re very focused on cities that have gone through a fair amount of stress and distress in the last couple of decades with deindustrialization. So we work in Cleveland, Indianapolis, downtown Niagara Falls, Detroit, … cities that have enormous potential. I love projects like this, where there’s this sense of what was known as palimpsest, a layering of history where it’s a mix of the old and the new. Twentieth-century building was about wiping everything away, a clean slate, building things from scratch. It did a lot of damage to our cities. Now we’re seeing a new interest in cities, but we have to hang on to the historic parts that give our cities authenticity and narrative as we build new things.

You said you really love Detroit. What do you love about it?

There’s a sense you can do big things there. A few years ago, I was invited to give a lecture in a series that took place on Monday nights at the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The organizer was from New Jersey, and I asked him why he moved here. He said, “Just think about it. You’re going to lecture in the Symphony Orchestra on a Monday night. Imagine trying to pull that off in Lincoln Center in New York City.” There’s this spirit of possibility that is incredibly fun and attractive. In our big, expensive cities, there are so many impediments for especially young people or immigrant groups or people of color to get something new off the ground because the investment level required is so high.

In Detroit, there’s this real sense that things are possible. That’s the spirit we’re trying to bring to Michigan Central.

Read more about the Michigan Central Project here, and don’t miss the interview with the Hour Detroit interview with the design director of The Book Depository here.

This story is from the Dawn of a New Era feature from the October 2022 issue of Hour Detroit magazine. Read more in our digital edition.

|

|

|