“When you say that you’re from Detroit, they expect you to be a badass,” says Joan Belgrave. She’s not talking about knowing how to throw a jab to set up an uppercut that will break a jaw. She’s talking about being a Motor City musician.

The veteran singer is among the local luminaries who make appearances in Detroit Jazz City, a new Detroit Public Television documentary on the town’s swing-soaked legacy.

The 30-minute film really hammers the point that jazz musicians from Detroit are different from those in the music’s traditional hot spots of New York, New Orleans, and Chicago. But I’m positive every jazz hub would claim it has the most badass musicians. The narratives we create about where we live help give our towns identity and importance, even if our stories are tinted by memory and myth. Even so, there’s zero doubt that a high number of Detroit musicians helped define modern jazz. The late trumpeter and Detroiter Donald Byrd asks this question in the film: “Why is it that this town, of all cities, would have [so many great musicians] — because, I mean, it’s out the way — and why is it that it became the music center?”

The answer, in part, is education. As the documentary — and former Detroit Free Press critic Mark Stryker’s recent book Jazz from Detroit — makes clear, music education in Detroit public schools was top-notch for much of the 20th century, even during the economic hardships of the ’70s and ’80s. Then in 2000, the state took over the bankrupt Detroit Public Schools and cut all arts programs.

But according to the Detroit saxophonist Wendell Harrison, music education isn’t complete until students graduate to the bandstand. “I’ve always thought the real education — I’m talking about jazz education — came from the jazz musicians performing it every week, making a living at it,” he says in the film. In that case, up-and-coming Detroit musicians had some of the best jazz education anywhere thanks to mentors like 90-year-old pianist Barry Harris (who moved to New York City in the ’60s) and 1970s Tribe Records members Harrison and the late trumpeter Marcus Belgrave.

“If you’re a jazz musician from Detroit, you mentor the next generation,” Stryker says in the film. “That’s your responsibility. And the people here take it seriously.”

So do the musicians in New York City, New Orleans, and Chicago; Detroit isn’t unique in that way. But the city’s musicians did influence modern jazz in a novel way — mostly by moving away.

In the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, Detroit’s Paradise Valley and Black Bottom neighborhoods were filled with Black-owned businesses and numerous restaurants, clubs, and hotels that provided opportunities for musicians. But those neighborhoods were razed in the late ’50s and early ’60s to make way for I-75 and I-375. Musicians had fewer places to work, and greats such as the Jones brothers (Elvin, Hank, and Thad), Ron Carter, Paul Chambers, Yusef Lateef, Milt Jackson, Kenny Burrell, and numerous others gradually left for New York City, where they found concert and studio work almost immediately because they were so skilled. Thus began the great Detroit jazz diaspora, spreading its badassery far and wide.

“Until you put all of these musicians together,” Stryker notes, “you don’t really realize how profound an impact that the city has had on the course of modern, contemporary jazz.”

A lifetime ago, I was the editor of a jazz magazine. My Uncle Stu was an avid reader, and it was his massive record collection in the basement of his home on Glastonbury Avenue on Detroit’s west side that introduced me to jazz. I was visiting him one time and he said, “I read the Geri Allen article” about the great Detroit pianist. “William McKinney’s name was spelled wrong. That’s a Detroit musician. You have to watch out for our guys.”

Detroit Jazz City does just that for all these badasses.

Watch it at dptv.org/jazz.

Plus, catch these local arts and culture exhibits…

Sweet Rides at the DIA

For most of my life, I’ve seen cars as functional devices — beasts of burden to get me from point A to point B — not objects of veneration. Later I came to appreciate a well-designed car that made the drudgery of getting around more enjoyable — and my minivan does just that. The 12 rides featured in the Detroit Institute of Arts’ Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950-2020 have also provided plenty of enjoyment, albeit with quite a bit more style than my Parentmobile. In addition to the actual vehicles, such as General Motors’ stunning 1959 Corvette Stingray Racer, there will be paintings, sculptures, drawings, and photos showing how American art and car culture often went hand in hand. You can check out Detroit Style at the museum from Nov. 15 to June 27. For more info, visit dia.org/detroitstyle.

Monochrome City

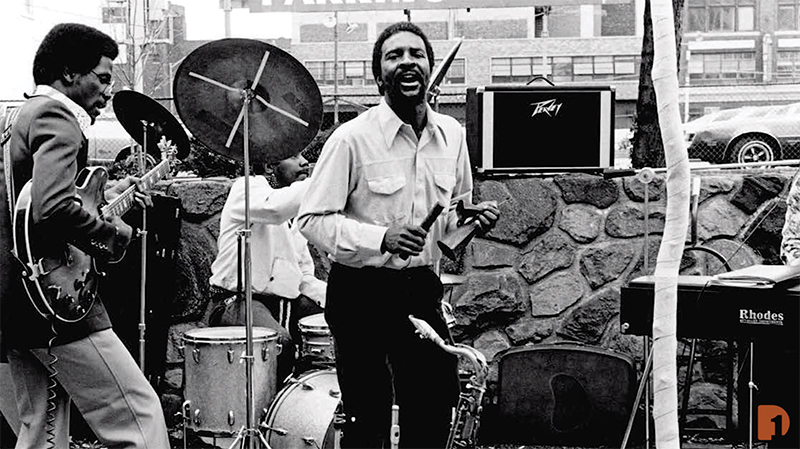

Running concurrently with Detroit Style, the exhibit Russ Marshall: Detroit Photographs, 1958-2008 features evocative black-and-white shots by the freelance labor and trade photographer. But Marshall also loved the city’s music scene and captured numerous musicians at places such as Baker’s Keyboard Lounge and various Detroit music festivals. There’s also a subset of pics he took in England and Eastern Europe between 1987 and 1990, but the Motor City is what fueled Marshall’s greatest work. See highlights and book a time to visit at dia.org/russmarshall.

Techno Time Capsule

The Movement Electronic Music Festival turned 20 in 2020, but like a keyboard with a faulty volume knob, it was a quiet celebration since the Memorial Day weekend mainstay at Hart Plaza had to go virtual. But the Detroit Historical Museum is doing its part to get your dancing shoes ready for next year with the 2000/2020: Celebrating 20 Years of the Electronic Music Festival in Detroit photo exhibit, which features a mix of pro-level shots in frames and a “live wall” of digital pics that can be submitted by fans. The exhibit runs until the next Movement fest (Pray to the techno gods that things have improved enough that it can happen in person). View the exhibit in person or at detroithistorical.org.

|

|

|