A nearly century-old Detroit tradition was just about dead in the water. Again.

American Power Boat Association racing had been a Detroit River tradition since 1916 — the year after the unlikely tag-team of Jack Beebe and John “Freckles” Milot piloted Miss Detroit to victory in upstate New York. More on that later.

In February 2015, the Detroit River Regatta Association was running yet another deficit and announced it couldn’t continue hosting the Gold Cup — an event that had been held exclusively in Detroit since 1990.

Why was that a big deal? Well, the Gold Cup is merely the oldest active motorsports trophy — first contested in 1904 on the Hudson River in New York. Compare that to spring chickens like the Daytona 500 (since 1959) or even the Indy 500 (1911).

At the race’s heyday, a half-million people would fill the grandstands, The Roostertail, the Detroit Yacht Club, city waterfront parks, and the beaches of Belle Isle.

Now the 2015 Gold Cup was gone — moved to Washington State’s Columbia River. And prospects of holding any hydroplane race in Detroit that year were sinking fast.

But the UAW-GM department’s multi-year partnership with the newly christened Detroit Riverfront Events Inc. — plus a group of 325 volunteers — would allow Detroit to at least host the 2015 UAW-GM Spirit of Detroit HydroFest.

At the time, H1 Unlimited chairman and Oh Boy! Oberto boat driver Steve David told reporters: “We owe it to our fans and the Motor City to do what we can to keep this great Detroit tradition going.”

And what a tradition it is.

Unlikely Heroes

In boat racing’s early days, Gold Cup winners earned a home-water-advantage right to defend the title.

While Beebe and Milot aren’t exactly household names, their unlikely 1915 quest has a bit of a murky backstory. The Miss Detroit boat designer’s name, however, may ring a bell: Christopher Columbus Smith of Chris-Craft fame.

According to The Detroit Yacht Club’s 125 anniversary book (in a section by 1989 Commodore Edwin C. Theisen), Smith raised money to build a boat through the Miss Detroit Power Boat Association. Its initial meeting included Hugh Chalmers of Chalmers Motor Co., Horace E. Dodge Sr., and William E. Scripps of The Detroit News.

Billy Metzger was scheduled to pilot Miss Detroit on Manhasset Bay in New York. But minutes before the first heat, he couldn’t be found (there’s speculation that perhaps he had a bit “too much fun” the night before).

Team organizers asked the crowd if anybody could drive a boat. Freckle-faced John Milot from Algonac stepped up. Without any preparation or protective gear, he and mechanic Jack Beebe jumped into the cockpit.

Unfamiliar with the course, Milot followed the other boats around the buoys for a few laps. The water was rough, apparently; Beebe took over driving after Milot got seasick.

Somehow, they won. And since most Miss Detroit association members were also DYC members, the venerable club would host in 1916. Miss Minneapolis took the title that year, but a tradition was born.

Tight Money, Deep Pockets

Apparently, another boat racing tradition was born that year. Money woes.

Miss Detroit association’s finances were strained. But a knight in shining armor — or perhaps a life jacket — stepped up to buy the boat: Garfield A. “Gar” Wood.

The former Ford dealer made a fortune developing a hydraulic mechanism for dump trucks. Wood also was sponsored for Detroit Yacht Club membership (a smooth move they’d never regret).

Wood became a legend. With his good-luck-charm teddy bears strapped to the steering wheel, he won every Gold Cup from 1917 through 1921.

He was also the DYC’s commodore from 1921-23, when its George Mason-designed clubhouse was built (Mason also designed the Masonic Temple and The Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island).

The Motor City and power boating became synonymous. Horace Dodge Jr. owned the 1932 Gold Cup-winning boat.

The sport had international appeal, as well. Count Theo Rossi (of Italian Vermouth fame) drove to victory in 1938. Apparently Rossi liked it cold, too; he was also an Olympic bobsledder.

Bandleader Guy Lombardo got in the game — as a boat owner and driver — winning the first post-war race in 1946 in the Tempo VI.

As a young man, Lombardo watched Wood set a speed record in 1920. But Lombardo broke that record with a heat average of 70.890 mph.

Faster, Stronger, Quieter

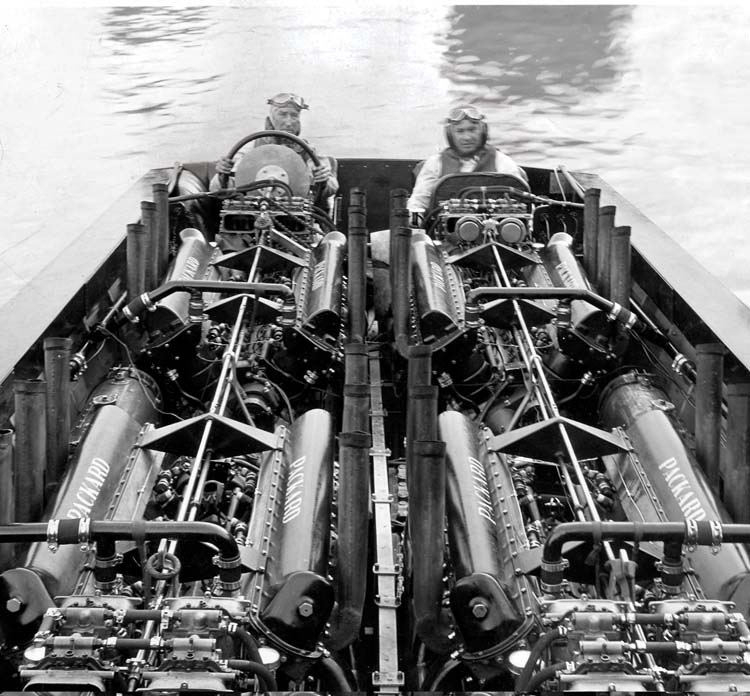

Lombardo’s record would be shattered again and again. Today’s H1 Unlimited hydroplanes are the world’s most powerful closed-course racing boats.

“They’re averaging 160 mph laps now. Average!” says Mark Weber, president of Detroit Riverfront Events Inc., the host and planning organization for UAW-GM Spirit of Detroit HydroFest.

On straightaways, speeds top out at over 200 mph. Today’s quieter turbines hum by without the characteristic roar of the old aircraft engines. It’s one drawback, Weber admits: “The thunder is gone.”

Weber knows what he’s talking about. The 14-time national champion has driven in seven Gold Cups. His father and father-in-law were boat owners. Two brothers also raced. A fourth generation of nieces and nephews now race.

Weber’s father used to make him finish chores before he could head to the races. “You could hear the roar … the thunder,” as far away as their home near Finney High on Detroit’s east side.

“Now, when my nephews are out on the course, you hear the boat slapping around the corner,” he says. “It makes more noise than the turbines.”

But they still kick up a lot of spray. Plus, the old days of delays as racers sat dead in the water are gone: The new boats are extremely reliable.

They’re safer, too. Early racers weren’t even strapped in. “Corners were like, ‘Yee ha!’” Weber says. “That’s when men were men. I drove them with cockpits. I’m a wimp. I’m OK with that.”

Weber is kidding. But he’s not joking. Hydroplane racing has always been a dangerous undertaking. In fact, in 1981 and 1982, Bill Muncey and Dean Chenoweth two of the sport’s most revered and victorious drivers died in racing accidents.

They weren’t the only ones.

All in the (Schoenith) Family

Despite hydroplane racing’s dangers, it gets in your blood. And it runs in families.

Ask any Schoenith.

Now known for their famed Roostertail entertainment complex, named for the fantail spray behind the speedy boats, the family had their Gold Cup debut in 1950 with Miss Frostie.

“My whole family was into boat racing,” says Michael Schoenith. “Especially my Uncle Lee and Uncle Jerry.”

His grandfather, Joe, was in the electrical business. “Someone turned him on to boat racing,” Schoenith says. Joe decided to buy the property next to Sindbad’s for docking their boats.

Shortly after Lee Schoenith won a Gold Cup in 1955, Joe got to thinking: Detroit needed a restaurant along the river to watch the boats go by. Near his docks was a place called Bill’s Marine Bar. He bought it and The Roostertail was born.

“I guess it was a famous hole-in-the-wall bar on the water,” Schoenith says, adding that when the water’s clear, you can still see the stumps that held the place up.

Roostertail soirees were legendary a tradition that continues. “All those parties” Schoenith recalls. “Problem is, I don’t remember them as a guest. I was behind the scenes. Working.”

It was fun, though. “Certain boats I loved, like Circus Circus. Miss Bud. …”

Then there were race weekend crowds with “2,000 people all over the building, legs over the seawall,” Schoenith says. “As a kid I was always hustling, selling cigarettes or canned beer in the parking lot.”

Today, the Schoeniths stick to their core business of catering (they’re kings of the prom season, holding 50 or 60 annually). There are already weddings booked hydroplane race weekend.

“You meet incredible people from every walk of life,”Schoenith adds. “This is one of those jobs where people leave thanking you.”

And come race time, Schoenith notes that the Roostertail boasts certain advantages. “It’s fully air-conditioned there are rest rooms. That’s a nice treat rather than standing outside.”

Just ask the fans across the river on Belle Isle.

Watching on Wild Side

While Roostertail guests munch shrimp cocktails in sweat-free comfort, it’s a whole other scene on Belle Isle. Race weekend is packed with partying hordes, many with their own traditions and rituals.

Connie Burke, a General Motors communications professional, has viewed the races from both sides of the spectrum, once as a guest at the Detroit Yacht Club, more often from just outside the club’s tony gates.

“I prefer the non-grandstand Belle Isle view,” Burke says. “It’s really creative the way people set up.”

Some load furniture into moving vans, then recreate their living rooms atop the trailer’s roof.

One of Burke’s friends was a painter. He’d take his VW bus out of storage once a year, pack it with scaffolding, and build his own makeshift grandstand.

They’d park “strategically next to the bathroom,” Burke says, nabbing a spot under the last shade tree before the beach.

“The races started out as a high school reunion, then a college reunion,” she adds. “For me, it was more reunion … less about the race.”

After Burke had kids, the tradition sort of petered out for her. “I think they continued long after I did,” she says.

The kids probably shouldn’t witness some island antics. One year, Burke had concert tickets the night of race day. But after a few too many adult beverages, she pretty much slept through an entire George Carlin show.

Not all island visitors were as “mellow” as Burke and friends. During the ’80s, crowds got a tad rowdy, leaving couches and garbage strewn on the shore.

How the ‘Other Half’ Parties

Race weekend is also an annual tradition for Detroit Yacht Club members and guests.

Mark Steffke, who started working at the club last March, is no stranger to parties on the water. He was at Bayview Yacht Club just up the river for some 27 years.

This year’s party should be packed. DYC hasn’t always had smooth financial sailing. But like the rest of the city, it, too, has turned a corner. “We’re well on road to recovery,” Steffke says.

Weber recalls another swanky scene when the pit area was at the Whittier Hotel. “All the race teams stayed there,” he says. “That was the big party hangout,” for racers and affluent visitors and locals.

In the mid-’60s, the Horace C. Dodge Memorial Pits were put in next to The Roostertail.

Someone Always Steps Up

Names like Horace Dodge allude to the fact that it takes lots of money to host the races. Weber cites a long tradition of people not letting them sink.

The DYC once sponsored. So did the Spirit of Detroit Association. Ditto the Chrysler Jeep Superstores. Race driver Tom D’Eath started the Detroit River Regatta Association.

Last year, the latest heroes emerged. UAW-GM signed a multi-year deal. But they only had 67 days to put the race together.

Longer lead times this year should make things a lot smoother, says Kris “Buffalo” Owen of UAW-GM, adding that the sponsorship is also “a huge boost for our charities.” This year, they’re raffling off a GM vehicle to benefit the March of Dimes. The winner — selected final race day — gets to choose from among four loaded vehicles.

The race also helps showcase all the union does for the community, and shines the spotlight on “charities that do some of the best work in the city,” Owen adds.

Charities such as Jack’s Place for Autism, The Boggs School, Detroit Hispanic Development Corp., and more get a share of the gate, plus proceeds from parking lot fees.

Building on Tradition

Bruce Madej hasn’t missed a Detroit River race since his uncle started taking him in 1955. Now that its existence is safe (for few years, at least) the ex-University of Michigan sports information director would like to “not only continue the tradition of having the race in Detroit, but having it grow in stature.

“We need more people to be aware of how spectacular this extreme sport is,” he says.

Organizers hope the 100th anniversary will help spread the word — and be a chance to celebrate the sport’s origins.

“Back in the day, you and I raced our pleasure boats,” Weber says. “‘My boat’s faster than yours.’ That’s how it all started.”

To honor that spirit, organizers hope to display boats from throughout the century, from Chris-Crafts and Gar Woods to Hacker-Crafts.

“They were all built on this river,” Weber says. “We want to celebrate the marine industry and what it meant to Detroit.”

Making Plans

The UAW-GM Spirit of Detroit HydroFest is Aug. 27-28. There’s a “Free Friday” on Aug. 26, which includes free admission to the grandstands and pits during practice runs. At press time, there were also plans to have a “Taste of Detroit” preview on Aug. 25 at The Roostertail. General admission parks are free on Saturday and Sunday. Grandstand seats start at $50; $180 for VIP Club Gold Cup. Visit detroitboatraces.com for details.

|

|

|