Betty Reid Soskin spent only the first few months of her life in Detroit — but she remembers well the story of what brought her family here from New Orleans.

Her father did something to offend a white man (which, in 1917, could have been just about anything) and was given until sundown to leave town. They picked up and moved to Detroit, where her father worked for the Ford plant.

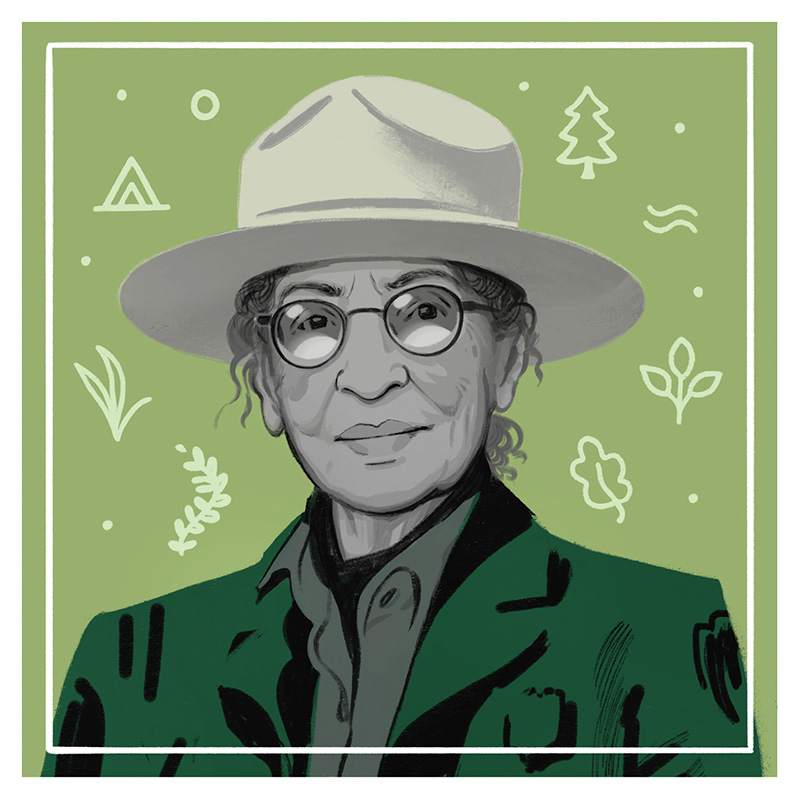

In September 1921, Soskin was born at Herman Kiefer Hospital. There began the life of an anti-war activist, musician, business owner, suburban housewife and mother, and, prior to her recent retirement, the oldest active National Park Service ranger in the United States.

Soskin assumed the role of ranger at Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California, when she was 85 years old. A woman of Creole and Cajun background, she told stories of the Black wartime experience — a perspective sorely missing from the common historical narrative. She suffered a stroke in 2019, which reduced her ranger activity, and formally retired March 31 of this year. But she still gives virtual talks with parkgoers every Thursday.

Born Betty Charbonnet, Soskin spent most of her early childhood in New Orleans and then Oakland, California, after her family’s home was destroyed by a hurricane. She was a file clerk during World War II for a segregated union, founded a gospel record store in Berkeley, California, and became vocal in social justice causes through the Unitarian Universalist church. In the ’60s, she sang and song-wrote her way through the Civil Rights Movement, a failing marriage, and a deep depression.

She has been showered with accolades over the years, including a Woman of the Year title from the California State Legislature, and in 2015 introduced President Barack Obama at the White House tree lighting.

From a large chair in her San Francisco Bay Area home, the small-framed, 5-foot-3-inch Soskin shared with Hour Detroit several chapters of her past century, including how she believes the world has changed for women of color.

Hour Detroit: You’ve spent years telling stories to parkgoers about the role of Black men and women in World War II. What’s a story that has stuck with you?

Betty Reid Soskin: In 1944, there was a naval munitions explosion that killed 320 men and destroyed two ships. Of those 320 people, more than 200 were Black. That was a time when the service was segregated, and Black men were being put in the most danger. The Black men were buried in a segregated military cemetery.

Why did you decide to take on the task of park ranger at the age of 85, after you had already accomplished so much?

I had worked as field representative for California State Assemblywomen Dion Aroner and Loni Hancock, and as such I was sitting in on the planning meetings for the park. I really had no sense that I wanted to be a park ranger, but I found myself on a four-year contract and working as a consultant when it was in the planning stages.

I have always lived my life in total surprise of my next steps. I never expected anything. I didn’t expect to do it for as long as I did. But I felt that there were women and people of the war whose stories had been ignored. Rosie the Riveter’s story was a white woman’s story.

I felt my role was expanding the story and pushing it beyond the limits. I felt as if what was locked up in me was an important part of the story that needed to be told.

Tell me about your days during the Civil Rights Movement, when you discovered your knack for songwriting. What role did music play in your life at that time?

It was a period of great disturbance. We were living in a mostly white suburb and faced quite a bit of racism. I guess I was in the middle of a mental breakdown. My husband gave me a guitar for my birthday, and I began to teach myself how to play. At first, I didn’t know I was writing my own songs. I thought I was remembering other people’s songs. Eventually, I realized they were mine. I was in the suburbs raising my four children while my husband was always working. Music was a way to travel without leaving my children.

Before music, I didn’t know who I was or who I would be if I weren’t a stay-at-home mother. Music helped me know myself.

As someone who has seen so many stages of societal evolution, how would you say life has changed for women of color over the years?

I guess I feel there’s never been a time that women of color have had more of a stage. There’s more of a stage, more of a platform. I think that we’re learning that we’ve always been on top of things. There have always been times when women of color have had it together, but we haven’t known it. We’re beginning to know now what has been true all along.

What is in store for you now that you’re retired?

I feel like I’ve lived so many lives. I think that I have learned that most people don’t remember much of what they’ve lived. The fact that I have such a good memory, it makes me really feel like I’ve lived.

I’m not sure what hopes I have now. I really feel like I still don’t know what I want to be when I grow up.

To join Soskin’s virtual chats and learn more about Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park, go to nps.gov/rori/index.htm.

This story is from the August 2022 issue of Hour Detroit. Read more in our digital edition.

|

|

|