As I learned more and more about Philip “Phil” Traci, a Shakespeare scholar at Wayne State University, it was easy to picture him on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. The popular professor would have put social media to good use. He cared more about the education of his students than the demands of academia, and he wanted to connect with them — to make them love Shakespeare as much as he did.

I imagined a provocative social post or tweet Traci might have sent students the night before class. He might have given them his take on a certain aspect of a Shakespeare comedy, asking them to think about it and come ready for good chat.

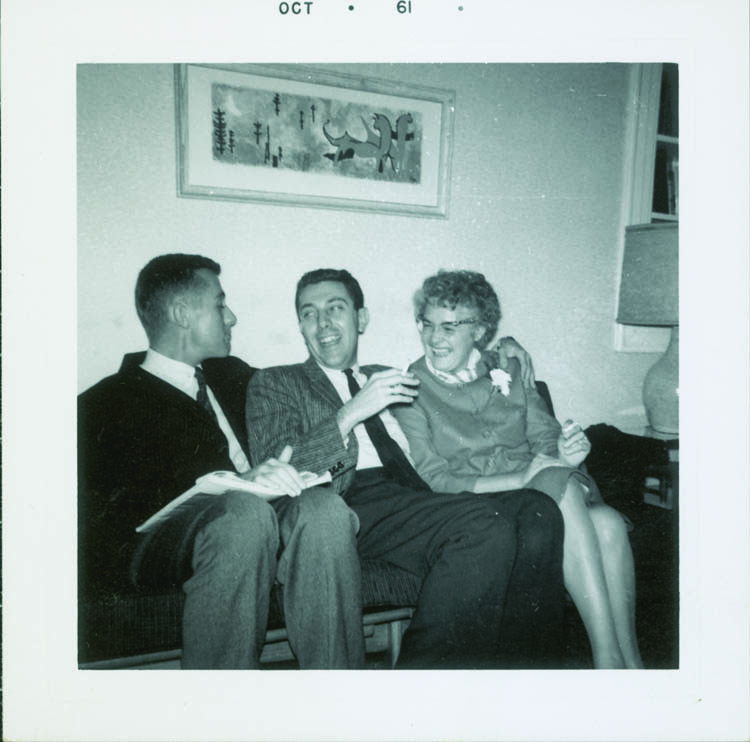

For his friends outside class, Traci might have constantly posted photos of gatherings in his custom-made gazebo, or among the flowers in his garden at his Nottingham Road home on Detroit’s east side. These photos might have shown up the day after one of the many gourmet meals he would cook for dinner guests, or one of the many parties he would throw to welcome a new season.

But Traci didn’t live in today’s age of social media. He made his mark on Detroit in the 1970s and ’80s, a time when people had to be far more creative and bold to make an impression. Traci did exactly that, building a reputation for himself at Wayne State and beyond as a man who understood human nature and the need to be loved.

Traci was also gay, and, unlike most of the men he was naturally attracted to, unafraid to be exactly who he was. One of Traci’s best friends, Lorne Hanley, can only marvel now at Traci’s disarming authenticity during the darkness of the early ’80s when AIDS, crime, and overt prejudice against gay men plagued Detroit as much as any other big American city.

“I can’t remember Phil’s address,” Hanley said last spring as we talked about Traci in Hanley’s home in Huntington Woods. “But I can remember his phone number. He’d throw it out to the crowd during lectures he gave on homosexuality. He’d tell them to use it, but ‘only if you like fat femmes.’ ”

All of this ended on a cold spring morning in 1984. Traci didn’t show up for his regular coffee date with Hanley. About an hour later, Hanley opened the door of Traci’s house on Nottingham Road where he’d attended so many parties and had long talks with his close friend. He walked in. He found Traci stabbed to death on the kitchen floor.

‘Nagging Feeling’

The first time I ever heard of Traci was when one of his former students, Ed Peabody, who works at Hour Media, sent me a one-line email. “I have an idea for a story,” Peabody wrote. “Who killed Phil Traci?” I did an initial Internet search on the professor, but all I could find were a couple of obscure references, including a couple of lines and a picture on the obituary website findagrave.com.

Then I met Peabody several weeks later at 9 a.m. on March 14 in his office. It was exactly 30 years to the day and hour after police showed up at Traci’s home to investigate the crime scene, a coincidence Peabody said he hadn’t realized when I suggested the meeting time. He called it bizarre, but not surprising, given his vivid, recurring memories of the slain teacher that had followed him throughout his career.

“He was funny as hell,” Peabody said of Traci. “I remember his way of instilling order in the classroom. He would say, ‘I can be June Allyson, or I can be Joan Crawford.’ ”

It wasn’t just Traci’s dramatic antics that made him stand out. More than any professor at Wayne State, Traci could invoke passion in his students for a subject they might have otherwise shunned. Peabody wasn’t fond of Shakespeare until he took Traci’s class in the English Department at WSU. He would end up concentrating on Shakespeare largely because of Traci, completing his senior thesis in 1983 on the public and private personas of Shakespeare’s kings.

Peabody was working at Autoweek magazine when he found out Traci had been murdered. He described feeling utter shock — a sense of devastating loss for his favorite college professor who had inspired the trajectory of his undergraduate studies. “I really feel like the world got robbed of someone great,” Peabody said.

Then time passed, and Peabody stopped hearing about the murder. There had been briefs of the killing in the metro sections of local newspapers and a couple of news segments with colleagues interviewed on camera. But really, that was it. Within weeks, Traci seemed to be gone.

Three decades later, that still bothers Peabody. “I’ve just always had this nagging feeling about who killed him,” Peabody said.

Peabody isn’t the only one for whom Traci’s death would become a life-altering mystery. But as I talked to the people who were closest to Traci, it seemed that both his friends and the police might have known all along one plausible scenario — that he was killed by a stranger he had invited into his home for sex. The Detroit police, however, didn’t pursue that lead, his friends say, and would end up losing the investigative file, along with any hope of discovering the truth.

After 30 years, Traci’s murder had become just another cold case among thousands of unsolved Detroit homicides.

The most important question Traci’s friends seemed to carry with them over the years, then, wasn’t really who did it, but why. Why would a man so loved by his colleagues and friends end up butchered and left to bleed out on his kitchen floor? Was it because he was gay? Was it because he was reckless? Was it just bad luck?

And why didn’t the police do more?

‘He Had a Following’

The question of police apathy in investigating the killing of Traci wasn’t unique to his case, nor was the widespread but unspoken belief that gay men had been the targets of violence for decades because of their sexual orientation. In fact, it was another murder in 1984 of a gay man in Detroit — and the subsequent lack of police involvement — that would end up as the basis of gay rights in Michigan (more on that later).

The circumstances and aftermath of Traci’s murder, of course, were unique to him, and those who knew him best have resisted the urge over the years to cast his death in simplistic terms. Still, their questions loom large, and the answers have been elusive — tangled up, they suspect, in the complexity of who Traci really was and the era in which he lived out his prime years.

Hanley in particular, who is also gay, said that even though Traci lived openly, he could not escape the necessity to some extent of keeping secrets and living a dual life in order to pursue the physical interactions and love that he desired.

“Truman Capote once said that he loved living in New York because you could live many different lives, but it wasn’t like that in Detroit,” Hanley said. “It was so much darker here in 1984. Anonymous interactions were normal for gay men because it made it easier for them to hide. There was a cultural impact from those anonymous interactions. There were consequences.”

Whatever Traci’s secrets at the time, it was what he showed to the outside world that people missed so desperately in the wake of his death.

A native of Cleveland, he was born in 1934 and grew up in a blue-collar neighborhood where loving to learn wasn’t the popular thing to do. He didn’t have a close relationship with his family in adulthood — his parents were ashamed of his sexual orientation. Anca Vlasopolos, his good friend and a retired WSU professor, said Traci had an extremely tough interior as a result that was easy to overlook because of his kindness.

“He sometimes told people that if you think you’re not tough growing up in a working-class neighborhood and liking books, then you don’t know what you’re talking about,” Vlasopolos said.

Vlasopolos and her husband, Anthony Ambrogio, had a young daughter named Olivia who adored Traci. He visited their home often and would entertain the child by listening to her knock-knock jokes and “laughing as if they were really funny,” Ambrogio recalled. The AIDS crisis was full-blown by then, and Traci always reassured the young parents that he was being careful. “I’m not going to kiss [Olivia],” he would say, “because we don’t know how it’s transmitted yet.”

Traci started teaching at WSU in 1970. He was sociable and self-aware and could gracefully defuse any trace of unease or tension that he sensed in other people. Traci had a noticeable deformity on his right hand in which a couple of fingers had become permanently bent and misshapen, apparently because of his attempt one time to change a flat tire. It had forced him to type out his dissertation with only his index fingers.

“To give you an idea of how long ago that was,” Traci would say, “It was when I was still dating girls.”

Traci, who was 49 when he died, specialized in Shakespeare scholarship, but taught a variety classes in the English Department during his tenure. Unlike most of his colleagues, Vlasopolos said, he had the rare talent of being able to elicit both admiration and the desire to learn from his students.

“You can be well-liked by students by giving everyone A’s and letting people play in class,” Vlasopolos said. “But Phil really demanded a lot from his students, and they knew it. He wanted to instill in them a true love for theater and Shakespeare, and he was very successful at that.”

Ambrogio was a graduate student in the WSU English Department and remembers Traci’s intolerance of sloppy thinking in literary criticism. “He was a hard guy. We’d be talking about a Shakespeare play, and someone would mention all the bird imagery,” Ambrogio said. “Traci would say, ‘So what? It’s nice to notice things, and that’s great, but what’s the point? Why is it there? What does it mean?’ ”

Traci pushed boundaries in his own scholarship. Queer studies (the broad study of sexual orientation and gender identity in a literary context) did not exist as a formal university program anywhere in 1984, but the WSU professor was in its vanguard, having already spent years examining the homosexual aspects of Shakespeare’s plays. He was fascinated by the slightly absurd ruse when male actors, who were the only ones allowed to play female characters, had to “re-disguise” themselves on stage when those female characters had to masquerade as men.

“The fluidity of gender, which we are so conversant in now, was still groundbreaking in the early 1980s,” Vlasopolos said. “Teachers weren’t talking about these things in their classes, but Phil did.”

In one instance with Lillian Back, a Wayne State grad student who would go on to become the associate director of composition at the University of Michigan, Traci questioned the way she was trying to talk about an aspect of The World According to Garp. In John Irving’s novel, which explores feminism and sexual identity, the character Roberta Muldoon, an ex-football player, is a transsexual. Back said she had the habit of always referring to Roberta’s character as “he or she.” It was something that infuriated Traci.

“He would say, ‘How dare you refer to her that way! She went through so much to be who she is!’” Back said. “It was that acknowledgment of diversity at the core level that made Phil so special.”

Despite Traci’s exceptional skill as a teacher and scholar, he thought of his students as peers, believing he could learn as much from them as they could from him. This was evident in excerpts from an essay published in the Detroit Free Press a few months after Traci’s death in a feature in which students wrote about the teachers who had been the most influential in their lives.

Deborah Laura, then a law student at Wayne State, described her first college Shakespeare class with Traci: “… he didn’t have students — he had a following. … He felt that discussion was the only vehicle by which he could both teach and learn. … Each of us was made to feel as though we had something important to add to the class, so each of us did.”

‘Fear is a Good Thing’

“There’s this thing that happens during memorials,” Jim Malek said over the phone from his home in Florida. “They transform the person into some kind of saint. But Phil was no a saint.”

Malek, a former chairman of the WSU English Department, had left two years before Traci’s murder to take a teaching post in Chicago. He returned for the first time to deliver Traci’s eulogy, knowing that his friend would have cringed at the typical eulogist’s caricature — the whitewashed version of the person.

So while others spoke at the funeral in quaint, polite terms, Malek kept it real by imagining what Traci would have thought of the whole affair. He no doubt would have been surveying the crowd, Malek said, taking notes on who took the time to show up and searching for signs of sincerity.

“He wouldn’t have tolerated a lot of mumbo jumbo,” Malek said. “He was the type of person who wouldn’t have let others — or himself — get away with intellectual dishonesty.”

When I went to Hanley’s home to talk about Traci, I had no idea what I expected to hear, but it probably wasn’t a detailed description of Traci’s sexual preferences and habits. And yet, amid photos of his slain friend and a hand-carved wooden bust of Shakespeare that had been one of Traci’s prized possessions, Hanley wanted to honor his friend with that kind of honesty, too.

“These things Phil did in private, they’re very much a part of his story,” Hanley said.

Hanley met Traci in the late ’70s while working as an assistant in the English lab at Oakland Community College. He had gone to a monthly author’s night at the Scarab Club, where Traci was reading. They kept in touch, and when Hanley broke up with the person he’d been living with, Traci helped him find an apartment in a building at the corner of Nottingham Road and Harper Avenue.

The apartment was close enough to Traci’s house that Hanley could look across the I-94 freeway and tell whether Traci was home.

This was part of Traci’s plan. He figured if he had Hanley living close by, it would be easy to ask him to housesit when Traci would go out of town to attend Broadway shows in New York.

Instead, the two became close friends — they never had a romantic relationship — and more often than not ended up traveling together. Traci also grew comfortable sharing with Hanley the things he did outside WSU — the things he didn’t go out of his way to hide, Hanley said, but certainly wouldn’t have openly shared with colleagues or acquaintances. They included details of the “assignations,” or secret sexual meetings, that had come to define Traci’s romantic life.

Traci knew firsthand that these types of encounters could be dangerous.

So did Jeffrey Montgomery, the well-known gay rights activist in Detroit who founded the Triangle Foundation in 1991 as a resource to combat both the rampant violence against homosexuals and the indifference of the Detroit police force.

“These were the most common anti-gay crimes at the time, what we called the pickup crimes,” Montgomery said. “The perpetrators were either gay haters or self-loathing men with gay tendencies. They would pick up men in gay bars, take them somewhere and beat them up or, in the case of a self-loather, have sex with them. In these men’s minds, they realized they had just had sex with something they hated, and they had to get rid of that image, often very violently and viciously. Unfortunately their victims had to pay the price.”

Traci insisted to Hanley that he could always take care of himself. He found out later the real story about how Traci’s fingers had become permanently injured.

It was years before when a man Traci met for an assignation threw him into a van, pulled a knife, and tried to kill him. Traci managed to escape with his life and a severe cut to his hand.

“Phil had this fearlessness about himself,” Hanley said. “But you know, fear is a good thing. It can save you.”

Hanley never stopped worrying about Traci, and Traci continued to set up encounters, which would usually take place in his home. Traci was attracted to black men who usually had wives or girlfriends. He took pride in the fact that he could satisfy them in a way a woman couldn’t. He kept

a stack of notes on his dresser detailing the things that his sexual partners liked.

To meet more men, Traci placed ads in gay publications like The Advocate and Michigan Connection. To Hanley, the ads seemed vague and open-ended, telling readers that Traci was “available for body worship.” Hanley never asked what that meant, but he said Traci’s phone rang all the time.

Because Traci and Hanley saw each other almost daily, they had a system set up: If Hanley couldn’t see the tail end of Traci’s car from his apartment’s living room window, it meant there was a visitor and he didn’t want to be bothered. Occasionally, Hanley would be at the house and a guy named Ronnie, a handsome, well-built black man who lived 10 blocks away, would call and want to come over. Traci always told Hanley that there was no need to leave — that Ronnie would walk upstairs, do his thing, and be gone in less than an hour.

It was a lifestyle that Hanley never wanted for himself. And yet, despite how uncomfortable it made him feel and how worried he always was for his friend, he knew it made Traci happy. “Phil was very courageous. He never tried to appear any different than he actually was. You had to take him or leave him.”

‘I Didn’t Want to Go Alone’

When Hanley went to bed on March 13, 1984, he couldn’t see the tail end of Traci’s car in the driveway. In the morning he went downstairs to meet up with Traci and a guy named Bill Johnson who owned the apartment building and usually joined them for coffee. Traci wasn’t there, and Johnson had already called the house. There was no answer, and that made Hanley worry.

“I’d had this whole routine with Phil for several years. Suddenly the routine was completely disrupted. I knew something was wrong,” Hanley said.

Johnson had a set of keys to Traci’s house, and Hanley told him they needed to go there — Traci might need them.

“I don’t know what I was thinking. I just knew I didn’t want to go alone,” Hanley said.

Hanley and Johnson trudged across I-94 through the snow to the house on Nottingham Road. They pounded on the front door and the windows. Hanley could see that the kitchen door was shut, which also usually meant that Traci was talking on the phone and didn’t want to be bothered. But there was still no answer, which made Hanley even more panicked.

Hanley went inside while Johnson stayed on the front porch. He opened the kitchen door and saw Traci facedown on the floor next to the stove. He had been stabbed multiple times, and there was so much blood that it had seeped through the wood floor into the basement. Hanley was told later his friend must have slowly bled out — that he must have been alive for a long time, and that he must have known he was going to die.

“I felt horror, probably,” Hanley said through tears. “I mean, I just felt sick.”

When the police arrived, they took Hanley to the precinct station. He was still in shock, but he thought they would want to interview him to get the investigation going. Several hours later, Hanley began to feel like he was under arrest. The police wouldn’t let him leave, asking him over and over where he had been for the past 24 hours. Hanley repeatedly told them to go to his apartment and look at his appointment book as proof that he’d been in the north suburbs all day working with clients for his drapery business. Later in the evening, he’d met his mother, who had just moved into a new house.

“You can call all of them,” Hanley told police.

Johnson had also already told the police that he had seen a strange car in Traci’s driveway the night before. Traci’s next-door neighbor corroborated the statement, telling them that the car’s vanity license plate said “SNAKE.”

Hanley said none of this seemed to matter to investigators. “You know in ‘cop land’ how they have this idea that if they don’t catch the [perpetrator], it’s a fast ride to never catching them?” Hanley said. “That’s for sure what I think the police thought. Here they had this guy who had found Traci at the scene. Plus, I was gay, and police assumed that gay men kill other gay men. They wanted to solve it and get it out of the way. ‘There. He did it. Done.’ ”

‘Just Look in the Phone Book’

Another gay man named Ron Hamilton, a public school librarian who lived about 5 miles away from Traci, was murdered in his home on the same night. From the start there was speculation from Vlasopolos, Ambrogio, and others that the killings were connected. Both victims were gay. Both had been stabbed. A rumor that a gay serial killer was on the loose had lingered for years in Detroit. How could the killings not be related?

The problem was, Hanley never heard again from the original investigators after they released him from questioning. He never saw the investigative files on Traci or Hamilton. Hanley found out later that other detectives apparently followed up on witness statements about the car with the vanity plate in Traci’s driveway.

The “scuttlebutt” was that they had tracked the owner down, a black male whose girlfriend provided an alibi for him. Hanley never found out his name or what he looked like. He heard the police couldn’t physically link the suspect to the crime; they let him go, and the case went cold.

When I requested the case file of both Traci and Hamilton this past March in an effort to confirm any of this, I learned that Traci’s file might be gone for good. “It is our understanding that the DPD has not been able to locate the homicide file of Philip Traci at this time,” the City of Detroit Law Department stated in a letter. They did produce Hamilton’s file — about 200 pages that the department redacted heavily to “protect the safety” of anyone connected to the 30-year-old crime.

There was no mention of Traci in the file, and police have never solved Hamilton’s murder either.

“What can I say when you tell me that Phil’s file is missing?” said Back, who had remained close to Traci after leaving WSU and had tried hard in the first few years after the crime to get investigators more involved. “I was always skeptical that the police ever really tried. They were very uninterested in solving gay murders. The whole effort was just pitiful.”

This was not just the cynical belief of a grieving friend. By 1991, Montgomery and the Triangle Foundation he formed to combat anti-gay violence were starting to expose a pattern within the Detroit Police Department, one of the investigators shrugging off crimes against gay people.

Montgomery had personal reasons for his crusade — nearly a year after Traci was killed, Montgomery’s boyfriend Michael was gunned down through his car window as he tried to drive away from The Gas Station, a now-defunct gay bar at Seven Mile Road and Woodward Avenue.

A few days later, Montgomery received an unsolicited call from a friend he had in the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office. According to Montgomery, the prosecutor told him “not to ever expect a resolution to the case.” Dumbfounded, Montgomery asked him why. “I was so naïve when I first started this,” Montgomery said.

In fact, police never assigned an investigator to the shooting. “Their attitude was, ‘It’s just another gay killing, why bother,’ ” Montgomery said. “We absolutely knew that police felt this way because the victims were gay.”

Compounding the situation at the time of Traci’s death was the cultural holdover from the ’50s and ’60s when it was technically illegal to be gay and homosexuality was heavily stigmatized. There was still overt prejudice against gay men among the public — and within police ranks — in the ’80s, Montgomery said. Detroit police were still setting up stings in gay bars into the ’90s. Gay men were still afraid of being caught.

Anonymous meetings, as Hanley stated, continued to be the default relationship mode. If a man did get beaten up, he wasn’t likely to report it to the police. The cycle continued — and the rumors of all the gay men getting killed never stopped.

“Did we all think there was a gay serial killer on the loose? Sure,” Hanley said, having no idea if the rumor was true. “I’d heard that they’d been pulling bodies out of Palmer Woods for years, and that no one ever did a thing about it.”

A more prosaic explanation for the police’s perceived indifference toward gays came from one of the investigating officers in the Hamilton case. Today he’s an administrator in the Oakland County government, having left Detroit homicide in the early 1990s. I had hoped he would be able to lead me to his colleagues who had worked on the Traci file. But he didn’t even remember Hamilton, let alone Traci.

The impression I got is that there was — and always has been — such a large amount of homicides that police have been historically overwhelmed. During the detective’s tenure in the ’80s, he noted that the number of homicide detectives went from about 90 to 50 to cover the entire city, straining resources further.

“The joke was, if you needed a list of suspects in a gay homicide, just look in the phone book,” said the former detective, who asked for his name not to be used because of his current position in Oakland County. “It wasn’t that we didn’t try. It’s just that some of these victims were with different men every day. In any homicide if I got one usable fingerprint out of a thousand, I was lucky. It was high stress, and the reality is, it was hard to solve these types of crimes.”

Today there are about 40 homicide detectives in Detroit, each juggling about 20 cases. The official cold case unit disbanded a couple of years ago, and countless homicides remain unsolved.

It was common as little as seven years ago for files to go missing, even as the department continues to digitize its records, said Sgt. Michael Woody, a public information officer for the Detroit Police.

“Every victim deserves justice,” Woody said. “At the same time, we’re talking at least 300 homicide cases a year for decades. Before you know it, you’ve got storage facilities that you’ve forgotten about.”

‘In My Blood’

Montgomery would go on to become one of the most prominent gay rights activists in Michigan, all of it stemming from the murders of gay men in Detroit like Traci in the ’80s. It was the earliest work of the Triangle Foundation, which is now known as Equality Michigan, that helped the DPD turn around the culture, Montgomery said.

“I have more respect for the Detroit police now than I ever did,” Montgomery said. “But that doesn’t mean gay people and people who are perceived to be gay still don’t experience prejudice and violence every day.”

As Traci’s friends and students moved beyond the darkness of 1984, some of that progress would provide a sort of objective peace. It doesn’t mean they’ve forgotten. It doesn’t mean that they’re still not angry.

“If I told you I think about him every day, you wouldn’t believe me,” Back recently said. “Phil was in my blood.”

At Traci’s memorial service, the poem No Requiem, written by his friend and colleague, Daniel Hughes, seemed to predict how his mourners would cope. Their attention would keep “wandering,” except when they tried “to think of something else.” They would try, and perhaps fail, to put their money down on ever seeing a happy ending on stage — “a scene from shabby hell when I was cut up in some poor low-down dated butchery in the worst play ever put on the boards.”

|

|

|