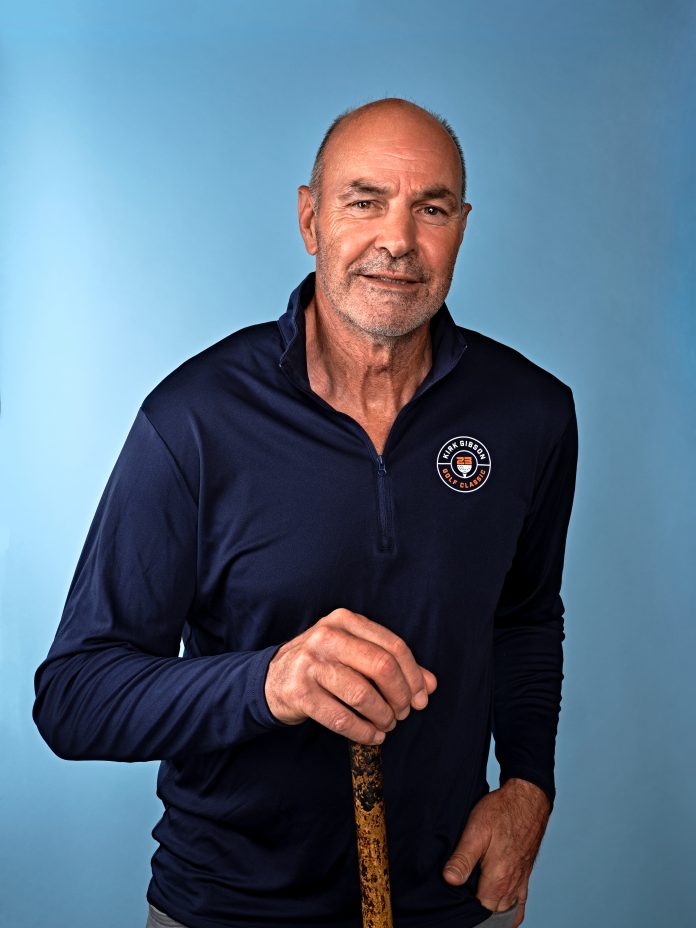

Despite the gradually debilitating effects of Parkinson’s disease, former Detroit Tigers legend Kirk Gibson seems energetic and upbeat for this Zoom interview from Florida.

On screen, he wears a gray T-shirt that says “Battle” and white-rimmed glasses that match his short white beard. Only his torso and head show on the screen, but he looks fitter than many men half his age, which will be 66 on May 28. He smiles a lot. He exudes positive vibes.

Not necessarily known for a sunny disposition in his robust youth, how does Gibson avoid depression over this unfair fate as a senior citizen?

“Oh, I’m depressed,” he says. “I’m depressed. There are dark moments. There are tough times.” Recently, he says, “Parky” had him discouraged. So, his wife, JoAnn, sat him down for a pep talk.

Although his voice, mobility, and facial expressions are limited, Gibson recounts this particular chat with great force, his clenched fist pumping and his face flashing the fire some Tigers fans might remember from his years as an explosive baseball icon of the Motor City.

“My wife said, just really emphatically, ‘You can do it! We’re gonna fight it! We’re not giving up!’” Gibson says of the moments he was low. “She was just like, ‘Stop that! Stop it right now!’”

Gibson returns this season as a commentator on Tigers telecasts for Bally Sports Detroit. He’s limiting himself to “around 40 or so” games out of 162.

“I’m much smarter about it,” he says of limiting work. “You don’t want to do seven games in a row.”

In the meantime, he represents the Kirk Gibson Foundation for Parkinson’s, a charity devoted to helping people cope with the baffling disorder of the nervous system with no known cause or cure.

The foundation’s major fundraiser this summer will be the seventh annual Kirk Gibson Golf Classic on Aug. 21 at the Wyndgate Country Club in Rochester Hills.

In 2015, when doctors diagnosed Gibson, the Waterford native speculated that it might be due at least in part to blows to the head suffered as an All-American wide receiver for Michigan State University’s football team from 1975 through 1978.

Does he still feel that way?

“Football, you know, hitting with the head, you could speculate that had something to do with it,” Gibson says. “And certainly, people that progress on to dementia-type symptoms, that could be the factor.”

Shortly after his diagnosis, in an interview with the sports website Bleacher Report, Gibson said, “We were taught to use our helmet as a weapon. I’d catch the ball and come right at you. I’d put my helmet on yours. As hard as I could. And I had a good, hard head.”

This had immediate effects.

“I saw lightning, stars,” Gibson recalled then, “and I got up and ran back to the huddle.”

Parkinson’s also debilitated the boxing champion Muhammad Ali, who was diagnosed in 1984 and died in 2016. However, a contact sport is not a necessary factor in Parkinson’s. Its most famous victim — and the major fundraiser for the cause — is Michael J. Fox, the retired actor.

Gibson says there may be many genetic or environmental causes, some not yet known. “I’m not smart enough to tell you what they all are,” he adds.

Instead, he counsels those with Parkinson’s with the zeal of a missionary. “Always looking to find a way to make people feel much better about where they’re at in life,” Gibson says.

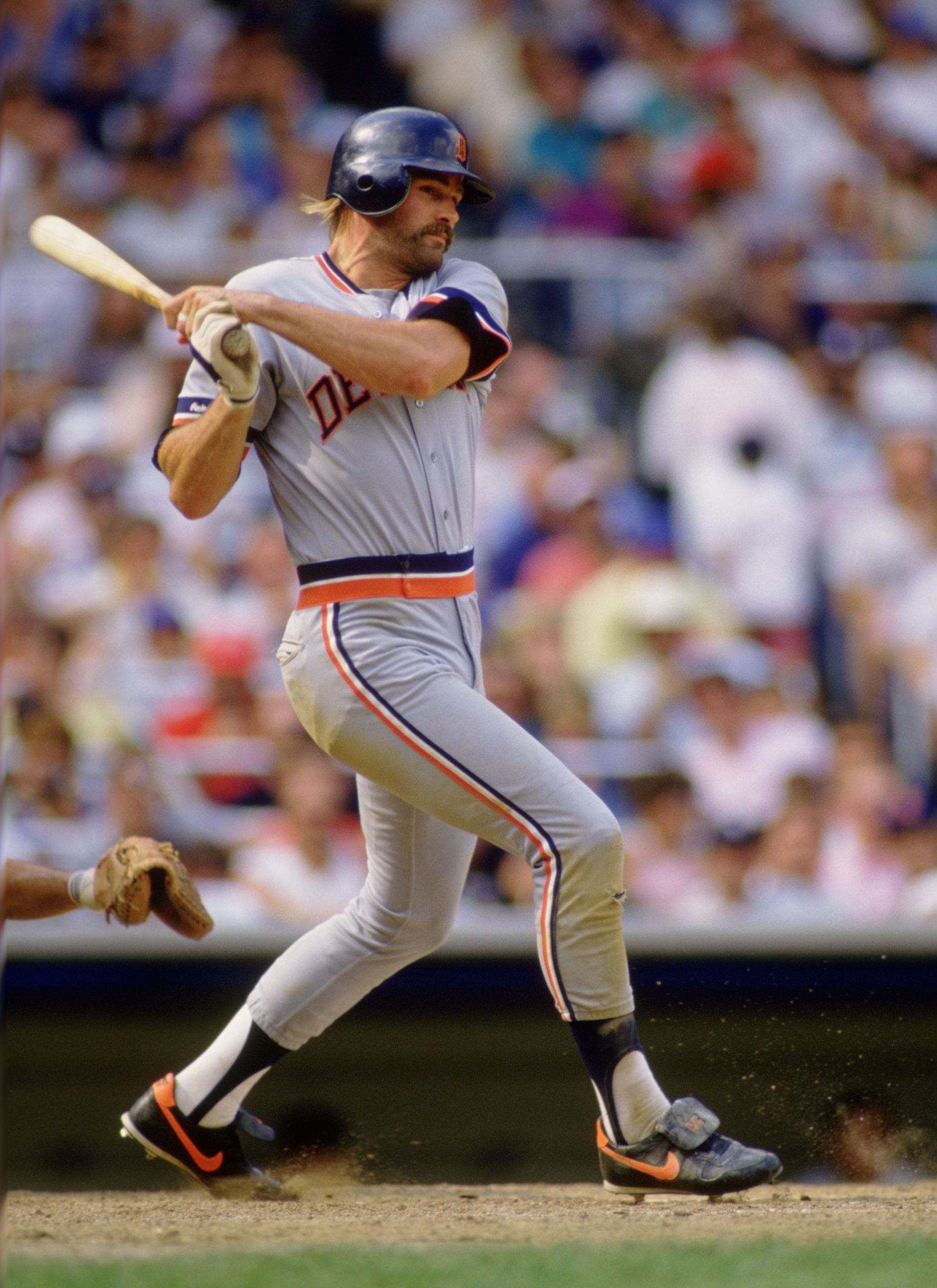

Fans under age 40 probably have little memory of Gibson — a speedy, left-handed, slugging right-fielder — as a dynamic Tiger of the 1980s generation. He first played in Detroit from 1979 through 1987.

After stints with the Los Angeles Dodgers, Kansas City Royals, and Pittsburgh Pirates, Gibson finished his playing days with the Tigers from 1993 to 1995.

Later, commanding the Arizona Diamondbacks from 2010 to 2014, Gibson was manager of the year in the National League in 2011.

But in Detroit, the young Gibson played baseball with a football mentality, a Tiger burning bright who intimidated both foes and teammates and frequently flashed a dramatic knack for powerful production under pressure.

Although best remembered nationally for his pinch-hit home run with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning that won Game 1 of the 1988 World Series for the Dodgers over Oakland, Gibson is best recalled in Detroit for his home run in the eighth inning of Game 5 of the 1984 Series off San Diego’s Goose Gossage.

That ball soared through the muggy evening air into the upper deck in right field in the now-demolished Tiger Stadium to seal an 8-4 victory that clinched that World Series.

Should the Tigers ever add more statues to their center field sculpture garden at Comerica Park, one should show Gibson — at that peak moment — striking a victory pose, as photographed famously by Mary Schroeder for the Detroit Free Press.

Her picture — against the backdrop of the misty, double-decked grandstands — shows no bat, no ball, no glove, no base. Not even a hat or helmet on Gibson’s head. Just Gibson with arms raised, fists clenched, eyes tightly squinting, teeth bared, (his right pant leg ripped and dirty) with longish blond locks bristling in the moist breeze, his face twisted in the most aggressive smile imaginable.

The photo — one of the all-time money shots of Detroit sports history — adorns the cover of Gibson’s intriguing and candid book Bottom of the Ninth, published in 1997 with co-author Lynn Henning. A mere year before that photo, Gibson wrote, he was, well, depressed.

While struggling with baseball — a relatively new sport to him at the time — he suffered injuries and endured hard feelings from teammates, his manager, the public, and the media with his loud, aggressive presence.

“I compounded all those setbacks by being selfish and immature,” Gibson wrote in his book. “I made life difficult for those around me. My image was becoming bad. I had a lot of bad habits. I was surly and demanding. I was unreasonable. … I knew that I was a jerk, and that my life was out of control.”

Gibson wrote that he changed his attitude after four days of counseling by an adviser “with an aura” at The Pacific Institute, which he called “a kind of Seattle-based clinic for the mind and soul.” He learned there “how to get out of the negative world I was living in.”

Not everything before that was bad. Many moments were spectacular. In the previous season, 1983, early in a game against Boston, Gibson launched a home run over the right field roof of Tiger Stadium.

Later in the game, with Lou Whitaker on first base, Gibson hit a drive into the outfield gap and caught up to Whitaker rounding third base. As he neared home plate, Gibson crashed into the umpire (who didn’t expect him) and the Boston catcher (who saw him coming).

Gibson knocked that ump unconscious, and the first-base umpire called Whitaker out and Gibson safe. As the medics raced out, Gibson merely jumped up and trotted to the dugout like a football player back to the huddle.

Tales of this Tiger, on and off the field, will be told for decades by Detroiters to their descendants. Even Gibson’s illness is public and dramatic. What is it like to be a living legend and a public person in his hometown?

“I don’t really look at myself that way,” Gibson says on Zoom. “In fact, I’m very humbled to have accomplished some great things. There were some tough things along the way, too. It didn’t just all come easy. I appreciate people who have better memories, way back in the ’80s.”

In those days, Gibson would ride his horse, sail his boat, hunt in the woods, fly his own airplane, and hit the hot nightspots. He was the epitome of physicality. He’s cut back on much of that, but, on Zoom, he waves a list of what he still does: golf, pickleball, table tennis, pool, and bowling.

“I don’t dance much,” Gibson says, adding that “it’s good for you” but he never could anyway.

But his body back in those days — his entire being — exuded energy, speed, strength, aggression, and power. The cruel irony is that Parkinson’s has stolen some of this. Also gone is Gibson’s fabled snarl, his 24/7 game face.

He doesn’t sense the irony when he reports that he had to learn how to smile again due to Parkinson’s. So, he is gently reminded that as a young man, he didn’t smile all that much even in the good times and that he now seems, somehow, happier despite his misfortune.

“I’m still competitive, but maybe not as intense,” Gibson says. “I was really intense. Maybe I’m paying for some of that now. But I think in life, people mellow a little bit as they get older.” Of his youth, Gibson recalls, it “maybe would come off that I didn’t care about people, that I didn’t ask them to move over. I went through them.”

“So, has Parkinson’s humbled me? Hell yeah. Yeah. It’s a battle.”

Indeed. That particular word — “battle” — is over his heart, on his shirt. He takes heart in helping others afraid to confront Parkinson’s.

Late in the conversation, Gibson reaches for a smartphone and calls up an inspirational poem called “Smaller” by Andy McDowell. It is the poet’s conversation with his two daughters about how his world grew smaller as Parkinson’s diminished him.

Gibson plays a recording over Zoom. It reads, in part:

“My world got smaller / My handwriting / My voice / My walk / My spirit / My balance / My space in the world I take up / It crept up on me in micro-increments / … And

then it became Big and Scary / … I may be smaller, slower / But I’m still me.”

This is the key, Gibson stresses to those fighting the same battle: You are still you.

People with this affliction can live active, happy lives in a loop of positive feedback. Gibson knows their fear. He recalls when his face and body “froze up” before a telecast on opening day 2015.

“I really didn’t want to go to the doctor because I was afraid of what I might hear,” Gibson says, “and what I heard was really scary. First thing I thought about was when I was going to die. After a while, over time, you realize it doesn’t have to be a death sentence. But it is scary.”

Looking ahead to the rest of his life, Gibson says, “It’s really humbling to realize what’s really going on in your life … and how much I still have to learn and develop to become all what I can be before I depart.”

This story is part of the 2023 Health Guide. Read more in our Digital Edition.

|

|

|