To be frank, the buildings aren’t glamorous. Sprawling, industrial, and largely neglected, what’s left of the once world-famous Ford Motor Co. Highland Park Plant does not draw gasps of admiration from passers-by driving along Woodward Avenue.

Nonetheless, you would be hard-pressed to find a more historic place — in metro Detroit, Michigan, or the world. In fact, the plant, built between 1909 and 1920, has been designated as a state and national historic site.

Anyone familiar with automobile history likely knows all of this, especially after the brouhaha last October celebrating the centennial of the world’s first automobile moving assembly line here.

What’s important to remember, though, is that this place changed the world not once, but twice — and in very short order.

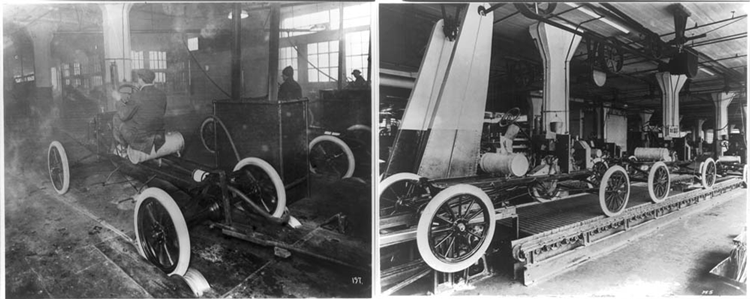

The plant’s Model T and its industrial innovations alone would have earned Ford — the man and the plant — world-history status. The moving line streamlined the assembling of the Model T’s 3,000 parts and cut the production time for each car from 12 hours to about 90 minutes. How do you top that for revolutionizing life in America?

But it was, arguably, what happened just three months later, on Jan. 5, 1914, that was the larger revolution — one that transformed life for ordinary working people, their families, and how they lived their lives.

On that day, 41-year-old James Couzens, general manager at Ford — and a future Detroit mayor and U.S. senator — stood amid a swarm of reporters in the plant’s executive offices, now gone. Henry Ford, then age 50, stood near a window as Couzens read from a prepared statement.

“The Ford Motor Co., the greatest and most successful automobile manufacturing company in the world, will, on Jan. 12, inaugurate the greatest revolution in the matter of rewards for its workers ever known to the industrial world. At one stroke, it will reduce the hours of labor from nine to eight, and … the smallest amount to be received by a man 22 years old and upwards will be $5 per day.”

Worldwide Impact

The news went viral, as we would say today, making headlines around the world.

Doubling daily wages to $5 sounds pretty unexciting today, but in 1914, it was beyond sensation. There was no middle class to speak of. Most people lived in poverty. They worked long hours at miserable jobs, and they could lose those jobs for no reason other than their accents, or if their boss just got tired of them.

No one could afford to buy anything beyond subsistence items, and they weren’t even assured of that. Until Ford’s Model T, Ford’s “motor car for the multitude,” automobiles were expensive toys for the rich.

“We live a pretty good life now — even those out of jobs,” says Robert Kreipke, Ford Motor Co.’s corporate historian. “Back then, it was a question of eating or not eating.”

Part of life’s misery existed right at the Highland Park plant. This new assembly line was dehumanizing. Many people worked six days a week, nine hours a day or more, with 15 unpaid minutes for lunch. The average line workers made $2.34 a day; some made less. It was hardly enough to live on, and there were no such things as insurance, pensions, or sick pay. People couldn’t even go to the bathroom on company time.

So they quit, by the hundreds, worn out and discouraged — and mad. Turnover reached critical mass — nearly 400 percent a year. This meant that Ford had to hire 53,000 men to maintain a workforce of 14,000 men, Ford wrote in his 1922 book, My Life and Work. It was unsustainable. But what could anyone do about it?

The Big Idea

Exactly who came up with the wage doubling idea, which was highly controversial and criticized by people in and outside of Ford, is unclear. Some said it was Couzens, others said it was Ford. Or maybe it was a committee decision. It depends on whose book you read.

The raise actually would be profit sharing paid in advance in regular paychecks. Also, there were conditions, Ford wrote. People who qualified were: “Married men living with and taking good care of their families; single men over twenty-two years of age who are of proved thrifty habits; young men under twenty-two years of age; and women who are the sole support of some next of kin.”

Some workers had to pass inspection, so to speak, by the company’s Sociology Department — which did home checks. So if you spent your nights at the bar, back off. But Ford had good intentions. “Back then, there were a lot of saloons and a lot of houses of prostitution,” Kreipke says.

Wrote Ford of the wage hike: “This was entirely a voluntary act … it was to our way of thinking an act of social justice, and in the last analysis, we did it for our own satisfaction of mind. There is a pleasure in feeling that you have made others happy — that you have lessened in some degree the burdens of your fellow men — that you have provided a margin out of which may be had pleasure and saving.”

Kreipke adds: “It was not a simple program. It was aimed at reducing the number of job categories, so you kind of flattened out the pay scales. It reduced the foreman’s power to dismiss people.” The new wages and hours also meant going to three shifts, requiring about 5,000 more workers.

Lining Up for Work

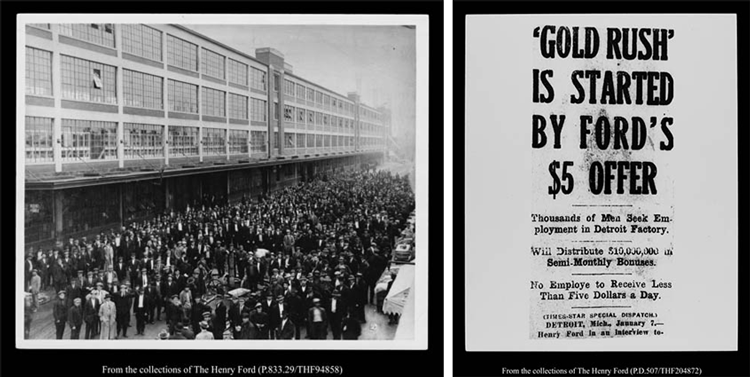

On the street, no one cared about the details. They just heard the words “five dollars a day,” and by 3 a.m., the day after the announcement, men started lining up at plant entrance No. 2.

At first, they were polite. But as more men came in the hard January cold, the line grew, and before long, it snaked several blocks. By 5:15 a.m., two more lines had formed, about 4,000 people. One local paper described a group “of all races and nationalities, unemployed men and men whose jobs suddenly had grown distasteful; rough-handed men in black shirts and soft-handed, white collared men eager to trade bookkeepers’ stools” for a job on the line at Ford. Many spoke foreign languages.

By 7:30 a.m., the crowd had grown to about 10,000. “ ‘Gold Rush’ is Started by Ford’s $5 Offer,” one huge headline read. Finally, it was announced from the employment office that they weren’t quite ready to take on new workers yet. The mob got angry. Police finally pulled out a fire hose, though there are no reports they ever used it. Eventually, the men dispersed.

An excerpt from a 1951 oral history interview of former Ford employee Al Esper helps paint the picture of the times and the days after the announcement. In early January 1914, his brother ran into Ford as Ford was taking his morning walk around Dearborn. His brother was on horseback, and the horse was getting a bit wild on a very muddy road. “The gentleman comes over, got ahold of this horse, and got talking to this brother of mine. … It happened to be Mr. Ford.”

Ford asked about Esper’s father, whom Ford knew. When Esper said his father had died a year before, Ford asked what Esper had been doing. Nothing, Esper replied. Ford told him to go to the Highland Park plant the next morning, in the main office, and tell the man there Ford sent him.

“That happened to be the time when they had ten thousand people on Woodward Avenue, inaugurating the $5.00 day at Ford’s,” Esper said in the 1951 interview.

He said it took his brother a couple of hours to work his way through “this mob of people.” The brother presumably got a job; Al Esper began working at the plant in 1917.

Lasting Legacy

The long-term effects of Ford’s wage hike became apparent. Not only did men work shorter shifts for a lot more money but also their wives and children didn’t have to work anymore — a huge quality-of-life advance.

Meanwhile, workers were finally able to afford the cars they built — thereby increasing the numbers manufactured and sold.

The middle class in America was born.

A Plan to Preserve the Highland Park Plant?

On Nov. 7, about 35 people attended a meeting at Highland Park City Hall to see the presentation of a Cultural Resource Management Plan (CRMP) for what’s left of the Highland Park Plant — a step toward preserving this historic site.

The group included key stakeholders in this long, laborious, and expensive quest. They included Deborah Schutt, executive director, and Harriet B. Saperstein, chairperson, both of the Woodward Avenue Action Association (WA3), which has a purchase agreement with the current owner of the site. The organization is raising funds to consummate the purchase.

Robert McKay, historical architect for the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office, explained that the goal of the CRMP was to essentially map out how the city can realize its vision to preserve this site. The presentation included details on gaining historic district status; an existing conditions survey; historical data; and an analysis and recommendations of development and tourism possibilities.

While much remains to be done, this presentation marked a turning point for the city, says Rodney Patrick, city council member, Highland Park native, and devoted preservationist. “This is a huge deal. We’ve never gotten to the point of a presentation, never had funding opportunities before. It was hard to see today coming six to seven years ago.”

Schutt explained WA3 started “putting our arms around this site” in 2010. The organization worked to bring together the stakeholders in the room that night.

One day, Schutt and the others hope, the site will join that of the Ford Piquette Avenue Plant, birthplace of the Model T, and the Ford River Rouge Complex as tourist meccas that bring alive the dynamic experience of 20th century Detroit’s biggest story. — Sheryl James

|

|

|