Carrie Bentliff was the last of the Detroit schoolgirls to die.

Three months earlier, she had burst through the doors of Detroit’s Tilden School, wild-eyed and screaming, a mass of flames. Somebody on that awful December day had thrown her to the ground and beaten out the fire, but not before her chest, shoulders, and neck were raw and her bountiful head of hair singed to the scalp. Amid the commotion — other girls were ablaze — she had gotten up and tried to walk home, but managed only a few steps before collapsing in shock. While several of her classmates quickly succumbed to their terrible burns, the plucky 17-year-old hung on until March 6, 1890, when she finally gave in to fever and internal injuries at home. Although the Tilden School fire has been lost to time (even comprehensive sources fail to mention it), it remains one of the most catastrophic events in the history of local schools and ranks as the city’s deadliest yuletide tragedy. Nine schoolgirls died from burns and several survivors were scarred for life in what the Detroit Free Press called “one of the saddest and most desolating calamities Detroit has ever known.”

That December, there was no snow on the ground and no nip in the air. Nonetheless, lighthearted preparations continued inside schools on the holiday programs traditionally performed before everybody adjourned for a two-week recess.

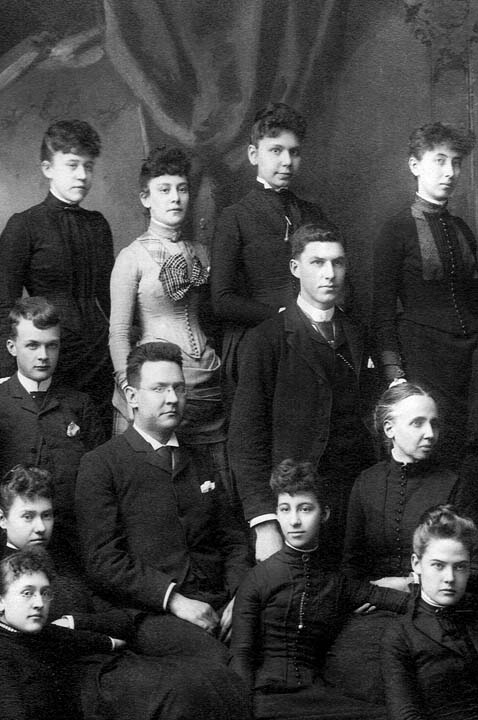

On Dec. 19, 1889, a small group of teachers and pupils staged a final rehearsal of their Christmas cantata inside Room A of the Tilden School, at Kirby and Seventh. The performance included 20 students, mostly teenage girls dressed in whimsical costumes made of cotton batting and mosquito netting. Helping direct the after-school session was Maud Priest, a 19-year-old who’d grown up loving books and saw education as her life’s work. Joining Priest in the second-floor classroom were two other young instructors, Hattie Sanders and Dora Woodsworth.

The room grew darker as the afternoon wore on. A candle was lit. One of the boys dutifully held the candleholder near the piano as Woodsworth played. Sometime around 5 p.m., the fidgety boy shifted his attention, a brief lapse of concentration that caused the glowing taper to graze the costume of Bessie Seeley. In a twinkling, the 13-year-old girl was ablaze. Classmates instinctively flocked to the screaming youngster, trying to beat out the spreading flames, only to have their own costumes catch fire. In seconds, the harmonious chorus that had filled the room became shrieks of terror. As Priest later related, it was “absolutely impossible to control the pupils after their lives were imperiled. They became panic-stricken, and a number ran right by a penstock in the hallway to get at water in the basement of the building.” Priest grabbed a piano cover and tried to smother the flames on several girls, scorching her own hands in the process.

Some girls ran out of the building, human torches that passersby tackled and rolled in the muddy street. Alarms brought horse-drawn ambulances and a fire wagon racing to the scene. In short order, the streets of the working-class neighborhood were lined with frantic parents. Marshall P. Thatcher was buying cigars at a downtown shop when he casually asked a friend entering the store what was new. “Nothing,” the man replied, “unless it is that several children at one of the schools were badly burned.” Thatcher bolted out of the store and ran practically all the way home. His heart sank when he saw the ambulance parked at the curb. His vivacious 13-year-old daughter, Nellie, a star pupil, had been taken inside. Her left arm and side were charred and her neck was raw.

Nearly all the boys and teachers in the room suffered minor burns helping extinguish the fire. Remarkably, a couple of the girls escaped with only singed costumes. However, 14 other students, all girls between the ages of 13 and 18, were grievously burned, most of them on their hands, arms, upper torso, neck, and face.

There were no dedicated burn units then, though one mildly burned victim was taken to Harper Hospital. The others were rushed home or to the closest physician’s office (most doctors worked out of their residence), or, if too critically injured, brought into the nearest welcoming household, where they were tended to by sympathetic neighbors until a nurse, doctor, or family members arrived. Many of the victims were barely conscious and had rapid but feeble pulses. Standard procedure called for immediately administering stimulants, such as placing ammonia under the nose and hot-water bottles by the feet and sides of the body. For those whose stomach could handle it, some whiskey was given in milk. Inside the Thatchers’ modest corner house at Hancock and Seventh, Nellie tossed her head from side to side, moaning deliriously. “She is a terribly burned child,” said the attending doctor, “and I fear the worst.”

The system of classifying burns according to their level of severity was not used then. However, contemporary descriptions indicate many of the schoolchildren had suffered what today would be regarded as third-degree burns, characterized by deep tissue damage and black, charred skin. Some had fourth-degree burns, where the fire not only destroyed the skin and nerve endings but also underlying muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Then, as now, fourth-degree burns usually result in death.

Among those clinging to life was Jennie Lankshear, 15, who was carried into the nearby home of Joseph Miller. “When the half-dead girl was placed on a bed in Mr. Miller’s house it was found that everything had been burned off her, except her shoes,” reported the Free Press. A doctor did what he could, applying dressings of linseed oil, lint, and powdered chalk. “All during the evening the suffering girl could be heard in an adjoining room, praying God to give relief.” It finally came that night, when she died.

Early Friday morning, 12 hours of torment ended for Bertha Moody, 14, when she slipped away inside her home. The girl’s father was the Rev. Edward R. Moody, a traveling evangelist who was frantically trying to arrange transportation back to Detroit when she died. Later that day, Edith Wheeler, 18, succumbed to shock and smoke inhalation. A janitor had thrown a bucket of water over her as she ran screaming from Room A, but by then the flames had burned all the clothes off her body.

The death toll climbed to four on Saturday, when Florence Westgate, 13, died at home, attended by her physician father. She had been badly burned about her face, arms, and upper torso, but was thought to be in survivable condition. However, she had also inhaled flames, scorching her lungs and leading to her sudden collapse.

Nellie Thatcher, whose injuries were so severe that doctors admitted she would be permanently crippled if she survived, died Dec. 23, surrounded by family. “She would gaze intently into one face, then into another, striving by scanning the countenances to ascertain just how they regarded her condition,” said A. W. Hilliard, who was present for her final moments. “Each one strove to appear natural and free from apprehension but it is doubtful the eager eyes of the dying girl were in the least misled.”

For nearly the entirety of Christmas week, there were no new deaths. The patients had been stabilized, their bodies and heads swathed in oil-soaked cloth bandages. The bandages needed to be kept moist, so that the cloth wouldn’t stick to the burns, and regularly changed, a procedure that could take three or four hours. Damaged flesh was softened with warm water for a half-hour or so before being carefully removed. Laudanum and other opiates were administered to help alleviate pain and to induce sleep. By early January, doctors were preparing to perform skin grafting on Bessie Seeley, the girl whose dress first caught fire, using skin from the arm of her sister. Carrie Bentliff seemed much improved, and soon she also would undergo her first skin graft.

“EVERYTHING HAD BEEN BURNED OFF HER, EXCEPT HER SHOES.”

However, all of the victims were highly susceptible to fevers, infections, and pneumonia, and several remained in critical condition. Edna Fonda, 13, had been burned to the bone in several places and had a deep burn over her jugular. By Dec. 31, death was imminent. She died before midnight rang in a new year and a new decade, the sixth girl to perish.

Two days later, on Jan. 2, 1890, Bessie Bamford, 14, became the seventh. Early the following morning, Lucy Remshaw, 15, died inside her family home.

Some criticized the teachers involved in the tragedy. Reporters attempted to interview Hattie Sanders at her residence, but were turned away. The young teacher, who had suffered minor burns and smoke inhalation, was racked by guilt. A coroner’s inquest revealed that it was Sanders who had brought the candle out of a storage cabinet, though all the teachers were negligent in not following unofficial school policy prohibiting any flame except a closed lantern inside the classroom.

At a January school-board meeting, an investigative committee released its report. The panel found “no blame resting anywhere,” but recommended a formal district-wide policy banning the use of flammable costumes and open flame in school recitals.

The traumatized survivors faced harrowing futures, physically and emotionally. The ongoing treatment of adolescent burn victims was nothing like today’s procedures, with advances in skin grafting, reconstructive surgery, antibiotics, rehabilitative physical therapy, and psychological counseling unavailable to them. Their bodies were still maturing, meaning they would literally grow out of their skin for several more years. The usual teenage concerns about body image and self-esteem were exacerbated by the patchwork of scars each wore.

Tilden School is long gone, torn down to make room for a freeway, and the names of the schoolgirls who perished were soon lost in the collective amnesia of old graveyards.

|

|

|