The speeches at the microphone were hardly the saddest part of the mid-June press conference in Ann Arbor attended by dozens of middle-aged and elderly men and women who say they suffered sexual abuse at the hands of Dr. Robert Anderson. The three survivors who spoke in the organized portion of the event offered devastating accounts, to be sure. Two were once big-time University of Michigan athletes — a football player and a wrestler — and the third was a student sports broadcaster embedded with the football team.

But it was the broader path of horror that Anderson blazed through the decades represented by all the other people present that was so crushing. Stories like that of a 65-year-old woman who recalled being fondled during a routine pelvic exam as an undergraduate in the 1970s, or the 77-year-old who, as a local in his mid-30s, saw Anderson for a physical in 1980 to participate in a local rowing club and wound up emotionally scarred for life.

These people were the collateral damage of the failure by iconic U-M football coach Bo Schembechler to strip this monster of his most important credential: his status as team doctor. Anderson, who died 13 years ago, is accused of sexual assault by hundreds of former patients — students and townies, men and women — over his 37-year U-M career.

Bo knew. An external investigation by the law firm WilmerHale said so, noting that Schembechler’s reply to players who said Anderson had penetrated their anuses with his fingers was to “toughen up.” Most damning, Schembechler’s own son, Matt, who suffered abuse, says Bo knew.

Lots of folks are rallying to Bo’s defense. Other Schembechlers and other former players say he didn’t know. Current coach Jim Harbaugh says he can’t imagine Bo being so dismissive. And Detroit Free Press columnist Mitch Albom wrote that the focus on Bo distracts from the real villain here, the actual sexual predator. Tainting Bo’s legacy when he’s been dead for 15 years and can’t respond is unfair, they say.

Yet that overlooks the worst truth: Bo alone could have stopped it. Technically, Athletic Director Don Canham, leaders of the University Health Service, and other U-M administrators also could have. In reality, though, Anderson, a football team fixture, was untouchable unless and until the Biggest Man on Campus, the coach, ceased to protect him.

Then, as now, U-M football’s head coach earned more than almost anyone else on campus. Players came and went, but Bo was the brand. He’s the guy whose skills at recruiting and organizing a team filled the world’s largest football stadium fall after fall, decade after decade.

Some victims, even now, seek to soften the focus on Bo’s culpability. Richard Goldman, the student broadcaster who spoke during that press conference about three incidents of Anderson’s attempted molestations, says Bo directed him each time to report the abuse to Canham. On the last occasion, he claims Bo went to Canham and screamed, “This is the third time that this has happened. Why have you done nothing?”

This account makes little sense, actually. Goldman’s incidents took place in the early 1980s. By then, WilmerHale says, other victims had complained to Bo, too. How could it be only the third time Bo had heard such stories? Goldman clearly feels he has to offer Bo’s legacy some protection despite everything — including the fact that Bo succeeded Canham as athletic director in 1988 and still didn’t fire Anderson, who had more than a decade of molesting yet to do. That’s the power of the myth of Bo Schembechler.

Bo could have done much more long before he became AD. Does anyone think Canham or the university president would have ignored Schembechler if he demanded Anderson’s dismissal in 1975? In 1980? In 1985? Why is it OK to Goldstein or anyone else that Bo kept sending students to Anderson year in and year out?

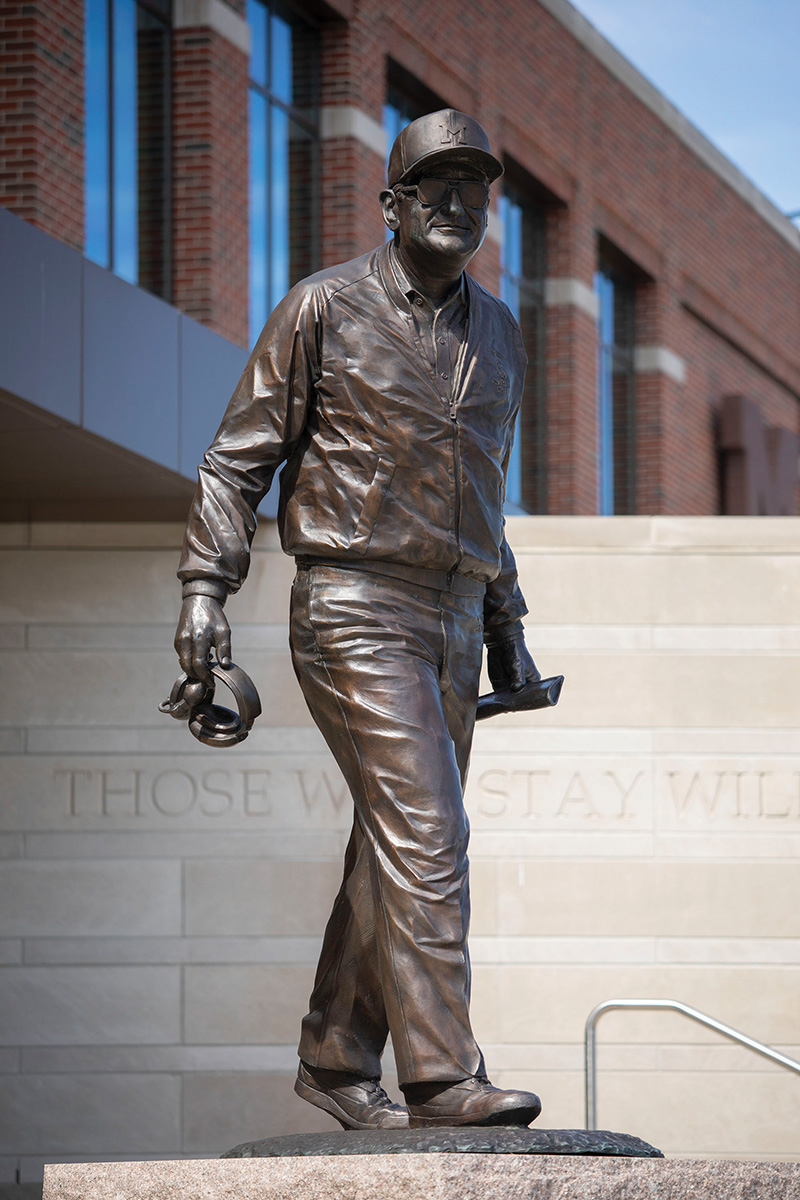

It’s not. That’s why his name and his statue must come down at the Big House. That’s why his most famous quote, emblazoned on all manner of U-M swag — “Those who stay will be champions” — now reverberates with horrific connotations. In the wake of the Anderson scandal, those abused by Anderson must have heard that axiom of endurance as: “Even if you’ve been sexually assaulted and the person you trust most in the world tells you to grin and bear it, you’re a quitter or a betrayer unless you stay put, play the game, and help us win.”

“This is hard for me,” says the 77-year-old Ann Arbor man whose price of admission to the rowing club 40 years ago was being fondled and subjected to a prolonged, unnecessary “prostate exam” by a predator. “I was at the Michigan-Ohio State game in 1969 when Bo was a rookie coach. My blood is blue. I have no joy in being a part of something that’s going to tarnish an institution that I’ve lived around all my life.”

No victim should feel the need to apologize for impugning Bo’s reputation. It’s not their fault; it’s his. And for that, there must be consequences.

|

|

|