As I look out over a pond that’s rippling gently under falling snow, the pine trees and fields covered in white, I’m writing this column in my Christmas-light-bright house, which rests on Bodéwadmiké (Potawatomi) land that was ceded through a coercive treaty.

A similar sentence begins “No, not even for a picture”: Re-examining the Native Midwest and Tribes’ Relations to the History of Photography, an online exhibition produced for the William L. Clements Library by two University of Michigan students with American Indian ancestry. Undergrad Lindsey Willow Smith (member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians) and Ph.D. candidate Veronica Cook Williamson (Choctaw ancestry, citizen of the Chickasaw Nation) used materials from the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography to explore ideas of consent, agency, and representation.

“No, not even for a picture” is succinct in its presentation — around 50 photos and documents — but its impact on me was enormous. Perhaps that’s because I’d felt a deepening combination of empathy and anger during a year that was an unmitigated disaster for nearly all but the wealthiest Americans, with minorities, including American Indians, enduring a disproportionate amount of suffering during the pandemic— as they did pre-COVID and likely will continue to do after everyone has been vaccinated.

What struck me most while viewing these photos of the Anishinaabe people — from the Great Lakes region and stretching through the upper and far West of North America — was how Native peoples were routinely offered incentives from the government, but always in the form of unequal treaties that were then torn up almost as quickly as they were written.

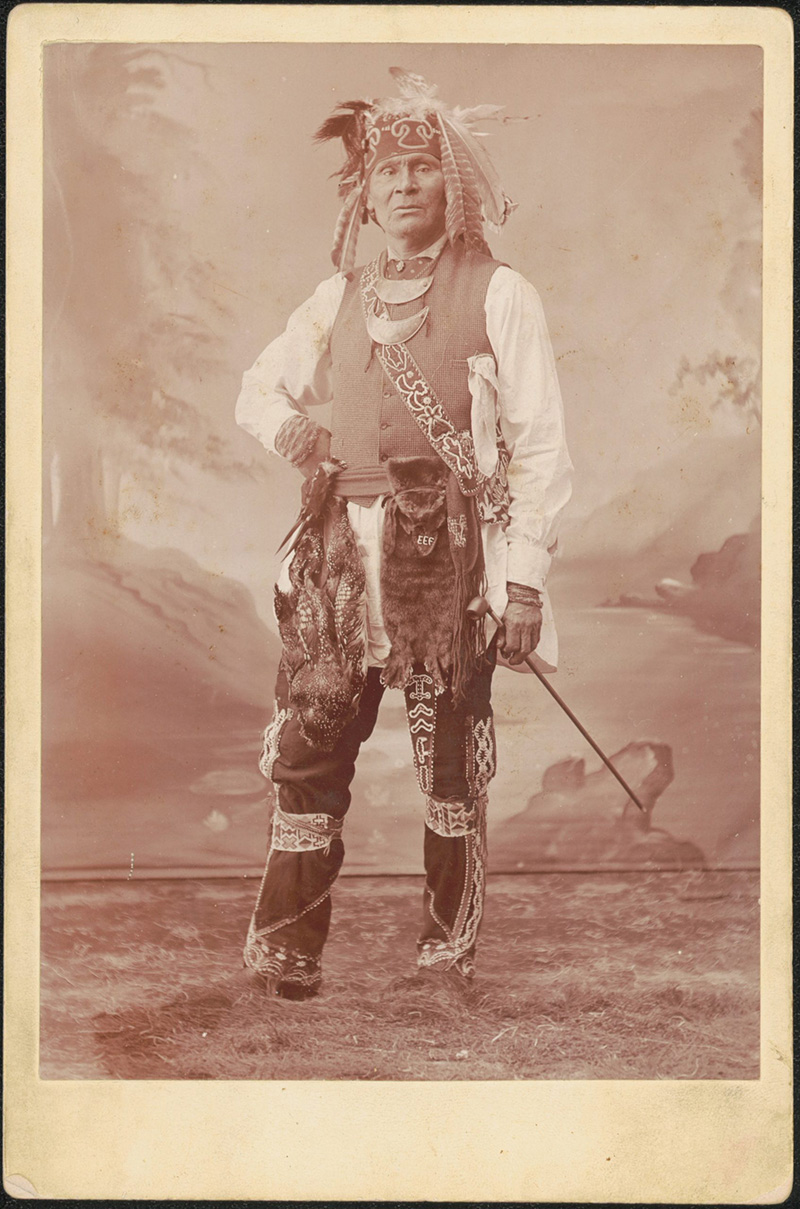

This precarious state of existence left some Great Lakes Natives from the “Three Fires” of the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi) open to exploitation, whether by having their lands “bought” for almost nothing, or by having their photos taken against their will for the titillation of a slack-jawed nation that wanted to gorge on “otherness.” Some Native Americans went along with the program, taking up Christianity or willingly posing for photos in European garb — or half-Euro, half-Native outfits — while many others, such as groups of Indian children being rounded up and sent to boarding schools, had no choice.

Some photos in the exhibit are in the form of postcards with descriptive text on the back,

and other images are accompanied by writings that originally appeared with the pictures. In almost every case, there’s some kind of moralizing, some kind of othering, some kind of deception in the text — or in the case of the photo that gives the exhibit its name, outright deceit.

Photographer John Wentworth Sanborn persuaded a reluctant Native man to stand at a corn-pounding machine — women’s work then — by promising not to publish the picture. Of course, the photo was published in 1891’s The International Annual of The Photographic Bulletin. Sanborn’s prose explaining how he photographed this adult man uses the same tone modern parents might use when talking about coaxing their reluctant children to pose for social media content. It’s the textual equivalent of patting the kid’s head while throwing a knowing wink to other parents — and it’s utterly insulting to a fellow human.

One of the most affecting parts of “No, not even for a picture” doesn’t feature images of people. The Displaced Portraiture section begins with photos of the Prairie Band Potawatomi, who were forced, due to a de rigueur treaty fracture, to relocate from Indiana to Kansas on a two-month march that came to be known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death. But the next photos in the section are of vacation cottages in Burt Lake, Michigan — home of the popular Camp Al-Gon-Quian summer camp. Because forced removals were becoming more common, the Anishinaabe started buying up their own lands in the 1800s in a bid to keep the U.S. government at bay. The Ottawa and Chippewa in the Burt Lake area bought more than 300 acres and registered the ownership titles with Michigan’s governor.

Even so, in 1900, a land speculator was able to buy the grounds out from under the Anishinaabe because of unpaid taxes. On Oct. 15 of that year, the new owner, enthusiastically assisted by the local sheriff, drove away the Anishinaabe, seized the land, and burned their homes. The land was then parceled out for non-Natives to buy and build on, which is one reason the area is now filled with idyllic cottages. The 1920s postcards in this exhibit show lovely little homes, all built on the charred remains of a civilization that had been driven away by European American greed and ruthlessness.

“No, not even for a picture” left me seething and needing to channel that anger into action. But how? One small step is to acknowledge that an issue exists, which is why I — and the exhibit’s curators — began our writing by acknowledging that where we live isn’t our land to claim.

Find the exhibit at clements.umich.edu.

|

|

|