Never underestimate the vaulting ambition of a middle child.

Charles Lang Freer, born the fourth of eight children in Kingston, N.Y., on Feb. 25, 1854, rose to become a leading industrialist. Although he had only an eighth-grade education, Freer was also an astute connoisseur, amassing a collection of American and Asian art in his Detroit home at 33 (now 71) E. Ferry, so impressive in quality and breadth that they’re now housed at the Freer Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C., a result of his gift to the nation upon his death in 1919. He also ponied up $1 million to build the gallery.

In Freer’s case, the usual division of being a left-brain (the logical side) or right-brain (the seat of creativity) type didn’t apply. He seemed equally exacting at bookkeeping as he was at discerning great art.

He owned the largest collection of works by American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) and became a patron and friend of the famously irascible artist. Freer accrued treasures from Asia and the Middle East when few Westerners knew anything about art from those exotic lands.

His house in the Cultural Center, which is on the national, state, and local historic registers, has been home to the Merrill-Palmer Skillman Institute, a research facility devoted to child and family development, since 1921. A doughty group called the Friends of the Freer House is committed to restoring the beauty of the sprawling Shingle-style home, once adorned with art. But few metro Detroiters passing by the building today likely know its history, or anything about the mysterious man who lived there.

Single, and Singular

By all accounts, Freer was quiet and reserved, social without being a socialite. In his correspondence, he was gracious and polite, occasionally evincing a glint of wit. “He was generally retiring; he didn’t like to draw too much attention to himself,” says Linda Merrill, a former curator of American art at the Freer Gallery, editor of With Kindest Regards: The Correspondence of Charles Lang Freer and James McNeill Whistler, and co-author of Freer: A Legacy of Art.

But Freer was no pushover. “He was a pretty ruthless businessman,” Merrill says. His shrewdness extended to collecting art. While in Japan, Freer suspected a dealer was trying to hoodwink him, took the man by the scruff of the neck, and tossed him out of his hotel room.

In a metaphorical way, Freer was married to business, then gave her up for a mistress — art. More literally, Freer was a lifelong bachelor. He fostered close friendships, but seemed to have little inclination for romance.

“There were rumors that he was a rake, but I’ve found no evidence to support that,” Merrill says. “A lot of people speculate that he was gay, but there’s no evidence of that, either, at least in his letters. He seems to me to be a sort of asexual being,” she says by telephone from her Atlanta home.

One thing certain about Freer is that he “was nobody’s fool” — either in business or in acquiring art, according to Susan A. Hobbs, another former curator of American art at the Freer Gallery, and a frequent writer on Freer and the American artists he collected. “I don’t think he suffered fools gladly,” she says when reached in Alexandria, Va.

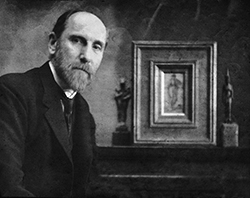

Pictures of Freer reveal him as fastidiously dressed, with a thick beard, receding hairline, and intelligent, appraising eyes, often peering out from behind spectacles. Whistler painted him. Steichen photographed him. Art collectors the world over knew his name. There’s a monument in Kyoto, Japan, honoring him. But his origins were humble.

Down to Business

To call Freer a rags-to-riches story would be accurate, but in a way it trivializes his achievements, because his story transcends mere riches. It’s what he did with his fortune that created his legacy.

When Freer’s mother died when he was 14, he began working to support his siblings and invalid father, toiling away in Kingston as a general-store clerk. Above that store was the office of railroad superintendent and Civil War vet Col. Frank Hecker, who would soon become Freer’s business partner, lifelong friend, and Detroit neighbor. In fact, Hecker built a chateau-style mansion on Woodward and Ferry, a stone’s throw from Freer’s house. Hecker’s 1891 home, once the headquarters of Smiley Bros. Pianos and Organs, now serves as offices for the Charfoos & Christensen law firm.

Impressed by Freer’s work ethic, Hecker hired him as his accountant. In 1876, Hecker moved to Indiana to supervise another railroad, and summoned Freer to join him. In 1880, they came to Detroit to work at the Peninsular Car Works, which made railroad freight cars. By 1892, Peninsular merged with the Michigan Car Co. to form Michigan-Peninsular Car Co., and Freer and Hecker bought out the original investors.

The two were “so tough together,” Hobbs says. “They had a strength of will.”

They were rich, but another windfall would bolster their wealth. Freer orchestrated the merger of a dozen additional companies and sold his stock, enabling him to retire in 1899 at the age of 45 and devote his attention to art. But first, Freer, who was boarding at a house on Alfred Street, in what is now Brush Park, needed to build a home sufficient for a 19th-century gentleman of means, as well as to showcase what would become a stupendous art collection. The home he constructed was a work of art in itself.

The House That Freer Built

In 1890, Freer hired Philadelphia architect Wilson Eyre Jr. to design his home. But he also enlisted the aid of American artists Dwight William Tryon and Thomas Wilmer Dewing, whom he commissioned to create paintings for the home. He also invited the artists to Detroit to offer advice on wall surfaces that would complement the paintings. Tryon created a quartet of paintings of the changing seasons for the main hall, in addition to two seascapes and a delicate painting titled Dawn, which hung above one of the hall’s two fireplaces. Dewing’s works graced the parlor, which included a lunette (semi-circular) painting of his daughter, which hung above the mantel. Abbott Handerson Thayer was commissioned to create an imposing painting called A Virgin, measuring 7 and one-half feet long by 6 feet wide.

“It was really a collaboration of client, architect, and American artists,” says Thomas Brunk, founder and board member of the Friends of the Freer House, as well as an art and architecture history professor at the College for Creative Studies and Wayne State University and author of the monograph The Charles L. Freer Residence: The Original Freer Gallery of Art.

The house, which stands just east of Woodward, is striking on several counts. The Shingle-style architecture was much more common in the northeast than in the Midwest. The lower level is bluestone, and the upper levels are shingled. Its horizontal planes and closeness to the ground are other unusual features for a house built in the Victorian era, when residences for the wealthy were typified by ornate Queen Anne-style homes with turrets, gingerbread trim, and an upward sweep.

Brunk says that Freer’s house is more in keeping with the simple Arts and Crafts style, both inside and out. “Freer’s house is definitely out of character for the time period,” he says, “and you can see that in comparing it to the Hecker house, which is a very ornate, towered, Victorian-style house. It was a pretty revolutionary design.”

It’s the only residential example of Eyre’s in Detroit, although he also designed The Detroit Club (of which Freer was a member), still standing at Fort and Cass.

Freer moved into his home in 1892. “It was a shimmering jewel,” Hobbs says.

Brunk agrees with the gem-like description. “If you ever held an opal ring up to the light, that’s exactly what the walls looked like,” he says of the parlor’s original surfaces.

The library, Brunk says, was dark green, “with a silver-green iridized surface on the woodwork,” while Freer’s bedroom was “pomegranate with silver flecks on the fireplace bricks.”

Achieving the precise hue on the walls wasn’t a case of looking at a few paint samples at the local hardware store and schlepping a couple of gallons of Dutch Boy paint home.

“It was a combination of paint and transparent glazes,” Merrill says. “It would look different at different times of day and different times of year, depending on how the light struck it. It made a very beautiful background for the subtle, tonalist paintings.”

Later, when Freer added Asian pieces to his collection, the effect was complementary rather than jarring. “Freer called it a spiritual kinship,” Hobbs says. “It was a view of the world that was delicate, evanescent, and elegant, that these works could resonate under one roof.”

Restoring the Home

There isn’t too much that shimmers in the house today. Many rooms are dull gray. But under that paint are flakes of color suggesting the former finish. Restoring the house to its original splendor is the mission of the Friends of the Freer House. The organization works in concert with Merrill-Palmer, which became part of Wayne State University in 1981. Friends board members want to ensure that the house is maintained by the university while respecting its historical significance.

“We care a lot about keeping Wayne State informed about the state of the house, and when they do have to make any changes, that they don’t change the integrity of the house,” says board chair Phebe Goldstein, who also attended Merrill-Palmer in 1951.

Despite their zeal, the Friends have had to tread gingerly. Keeping the bones of the house — from the roof to the furnace — maintained is one thing, but restoration is a much more delicate, deliberate matter.

“It’s not realistic to try to turn the house into a museum,” says board member William S. Colburn, a historic preservation consultant who also conducts tours of the home. “The goal is to make the house meet contemporary needs while restoring as much of the original fabric and character of the house as possible, and doing that in a highly informed and academically researched level,” he says.

Renovations are slow but steady. Last summer, the dining room was painstakingly restored. A heat gun peeled away years of old paint. The original surface was exposed, but the glazed surface had turned blotchy. So the walls were painted in a two-toned lemon-yellow that closely resembled the original color.

Currently, a reproduction is being made of Thayer’s oil painting A Virgin, which originally hung along the staircase. There’s another reproduction of Tryon’s Autumn, part of his Four Seasons collection that Freer commissioned, hanging in the main hall. A replica of Dewing’s lunette (semi-circular) painting of his daughter is in the parlor.

There are more than a few vestiges of the home’s former glory, including vine-like, wrought-iron light fixtures, elegant wood carvings and roundels in the main-hall mantel, leaded-glass ogee and oriel windows, cozy inglenooks, an imposing oak staircase with a basket-weave design, a leaded-glass skylight, fireplaces with glazed bricks, and another fireplace with Pewabic tiles, crafted by Freer’s friend, Mary Chase Perry Stratton, co-founder of Pewabic Pottery.

Fortunately for the Friends, the Merrill-Palmer Skillman Institute heartily supports the renovations. Director Laura McCloskey believes the improvements will reflect well on the institute. “Renovating this beautiful house will bolster our own visibility,” she says. ”We’re trying to build a national and international profile for the institute and recapture the vitality it used to have during the Great Depression and in the post-war period. There was a lot of famous research going on here.”

But the institute hasn’t always been so vigilant about the home’s architectural integrity. In 1952, during a modernization frenzy, the library was partitioned into two classrooms, the kitchen became offices, and one of the exhibition room’s skylights was removed and replaced by a dropped ceiling with fluorescent lights. Woodwork on the second floor was painted, and the main hall’s mantel and staircase were “antiqued” with a greenish color.

Also, in 1995, Wayne State made some renovations, including the addition of an elevator and bathrooms. Colburn concedes some changes were necessary, and one was even good: removing the partition in the library.

Years of Expansion

In 1890, Freer went to London to meet Whistler, whose work he deeply admired. The artist could be highly sensitive (see first sidebar, below), but Freer won him over. He assured Whistler he wouldn’t resell any of his works, a practice the artist despised. In his correspondence, Freer wrote of buying art as a “joint ownership” with the artist. It struck the right chord with Whistler.

In 1894, Freer embarked on the first of five voyages to the Middle East and Asia, excitedly buying Rakka ware and ancient manuscripts in Syria and Egypt, bronzes in India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), scrolls and screens in Japan, and jades and ceramics in China and Korea.

But acquiring all that art required places to exhibit and store it. In addition to adding vaults in the basement, Freer built an exhibition room in 1906, with red lacquered woodwork, green and gold brocade fabric for the walls, and a leaded-glass skylight. In 1911, he added another exhibition room with a Pewabic Pottery hearth in “Egyptian Blue” tiles, sliding panels to regulate sunlight from the windows, and leaded-glass skylight.

Freer was exceedingly particular about the way art was presented, preferring natural light from above. Brunk says a retractable roll of linen was placed over the skylight to diffuse the light. “He wanted the objects to be put to their best advantage, and Freer was conscious of the different qualities of light, depending on the time of day.”

Freer also preferred ample space between objects, a departure from the crowded way art was often displayed. ”Freer wanted the observer to have ‘breathing space’ between the paintings,” Colburn says. “He wanted to avoid overloading the senses.”

Freer picked up pointers about art from Whistler, Tryon, and Dewing, as well as from art collectors, especially Ernest Fenollosa, an American authority on Japanese art. But essentially, he was self-taught. Freer also had a keen eye that enabled him to spot — and buy — masterpieces.

On his Asian excursions, “he was going mainly on instinct,” Merrill says. “Even today, curators marvel [at an object] and say, ‘How in the world did he know how important and precious it was?’”

Freer acquired thousands of works, but the piéce de résistance came in 1904, when he bought the entire Peacock Room, an ornate blue-and-gold dining room that Whistler had designed for a wealthy English patron, Frederick R. Leyland. It was dismantled and brought to Detroit in 1906. Naturally, it necessitated another addition. Its centerpiece is a painting, The Princess From the Land of Porcelain, but it also includes shutters with gold-painted peacocks, a peacock mural, Prussian-blue leather walls, a ceiling embellished with Dutch metal and green-and-blue painted peacock feathers, and gilded recesses to display pottery.

At the Freer Gallery in Washington, only a small percentage of its collection is exhibited at one time, but the Peacock Room is always on display, and “people head straight for it,” Hobbs says.

Last Days, and Dispelling Myths

In 1906, Freer bequeathed his collection (including the Peacock Room) to the Smithsonian Institution. Construction on the Freer Gallery of Art, designed by Charles Platt, was begun in 1916, and it opened in 1923, after delays caused by shortages during World War I.

After Freer suffered a stroke in 1911, his health continued to deteriorate because of the effects of syphilis, which attacked his nervous system. In those pre-penicillin days, there was no cure for the disease, which can lead to paralysis, blindness, and even insanity. Treatment was almost barbaric. “Mercury was rubbed into the soles of the feet and the palms of the hands,” Brunk says. Freer stayed in New York City to be near his doctors. He died there on Sept. 25, 1919, and was buried in Kingston, N.Y.

A misconception that lingers even today is that Freer scorned Detroit by not keeping his collection here. But there are solid reasons why the art is in the nation’s capital.

“Whistler made it very clear to Freer that if he helped him to build the premier Whistler collection, then that collection would have to be displayed in a city where tourists went,” Hobbs says. “Whistler wanted his works shown where he’d get the most fame out of it. It’s not fair to blame Freer; you have to go where the ground is most fertile.”

And Detroit was not the most fertile place for culture in those years. Freer did his part, however, inviting American artists to The Detroit Club and organizing exhibits there. He was active in the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts and lent objects to Detroit’s Museum of Art and to U-M for exhibitions. He donated $10,000 to acquire the land for the current Detroit Institute of Arts, built in 1927.

He supported the fledgling Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and gave anonymously to many charities, Brunk says. He also never moved from Detroit, though he could well afford to.

“What people don’t understand is that the Museum of Art [the precursor to the Detroit Institute of Arts, which was on East Jefferson] was a private organization,” Brunk says. “It didn’t become public until 1919.” Furthermore, museums can, and often do, sell donated art.

“Not long after he died, the value of Tryons and Dewings went down,” Colburn points out. “Their value shot up again later, but they could have been sold when they weren’t so valuable.”

Colburn is more pensive than defensive when reflecting on the bequest. “Rather than looking at what we don’t have, we should look at what we do have — and that’s Freer’s house, which was really a part of his collection,” he says.

“When Freer donated his collection to the Smithsonian, it was a gift to the entire nation, and, in fact, the world. It reflects well on Detroit, that a Detroiter did something so important.”

There will be a lecture by James Steward at 3 p.m. Feb. 10 at the Freer house, 71 E. Ferry, Detroit, on Freer and his artistic relationship with U-M. Admission is $5, followed by a tour. Reservations required; call Rose Foster at 313-872-1790. An April 13 lecture at 3 p.m. focuses on Freer’s aborted plans for a Detroit bicentennial monument. Membership info on the Friends of the Freer House can be obtained by contacting Foster. For info on the The Freer Gallery of Art, go to asia.si.edu.

The Rocket’s Red Glare

American expatriate artist James McNeill Whistler is best known today for the portrait of his sitting mother, but in the late 1870s, his fame centered on a lawsuit that became a media event. Whistler’s impressionistic Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, which today hangs in the Detroit Institute of Arts, created plenty of sparks when the reigning British art critic, John Ruskin, saw it at a London exhibition in 1877. Pen dipped in vinegar, Ruskin fired off a caustic review, attacking the artist as much as the painting. He referred to Whistler as a “coxcomb” with “the Cockney impudence to ask 200 guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

Outraged, the equally prickly Whistler, who incidentally was not Cockney but hailed from Massachusetts, shot back with a libel lawsuit. Linda Merrill, whose book A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin, chronicles the dustup, says Whistler was understandably upset, but he had other motives. “He was heading toward bankruptcy when he brought the case against Ruskin, and I think he was hoping to earn substantial damages to offset his debts,” Merrill says.

Even though Whistler won the 1878 case, it was a Pyrrhic victory. He was awarded damages of one farthing, equal to a quarter of a penny. Plus, Whistler was burdened with paying court costs.

“A lot of people said it was unfair, and that Ruskin should have been made to pay Whistler’s costs,” Merrill says.

With the right timing, Whistler’s Detroit patron, Charles Lang Freer, no doubt would have come to the artist’s aid, but Freer didn’t start collecting works by Whistler until the late 1880s and didn’t meet the artist until 1890.

Still, Whistler had the last laugh. He later sold The Falling Rocket for 800 pounds, an amount that would have floored Ruskin, who eventually went insane.

— George Bulanda

Detroiters Who Made Capital Gains

Travelers impressed by the beauty of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., can thank three Detroiters for their role in creating it.

The mall was the brainchild of James McMillan, a U.S. senator and former business competitor to Charles L. Freer. An admirer of man-made and natural beauty, McMillan was behind the campaign for Detroit to buy Belle Isle in 1879, and filled his East Jefferson home with paintings.

After he was elected to the Senate in 1889, McMillan believed the nation’s capital needed something to distinguish the city. His plan for a stately area of monuments, green space, and museums was gaining momentum until his death in 1902.

Enter another Detroiter (although he was born in Ypsilanti), Charles Moore, a former journalist and political secretary to McMillan. He made speeches to drum up support for the mall. Among those who heard Moore’s plea was Freer, and plans to house his collection at the Smithsonian Institution were hatched. Freer formally made the offer in 1904.

But it was a hard sell. The Smithsonian balked at Freer’s restrictions, which stated that none of the works could be lent or sold, and that nothing could be added. Later, he relented on the Asian collection, which has grown considerably since his gift.

A Smithsonian delegation was dispatched to Detroit to view Freer’s collection. They were hardly bowled over. Freer was unimpressed by them, and wrote, “What they do not know about art would fill many volumes.”

That was at least partly true. Linda Merrill, co-author of Freer: A Legacy of Art, says, “They didn’t realize what Freer had. They recognized that the Whistler collection was valuable, but in those days people didn’t know about Asian art.”

But Moore came to the fore again, and petitioned President Theodore Roosevelt, who leaned on the Smithsonian to accept the gift. In 1906, the regents did just that.

In gratitude, Freer commissioned an artist to paint Roosevelt’s portrait. His name was Gari Melchers — another Detroiter.

— George Bulanda

|

|

|