It’s circa 1956. Young Martha Reeves, her 10 brothers and sisters, and all the other youngsters up and down Riopelle Street are united in a single goal: to enjoy Saturday night to the fullest in advance of Sunday’s all-day repentance.

“In my day,” Reeves recalls, “if you saw a bunch of Black folks standing on the street corner, they were trying to learn how to sing doo-wop. And doo-wop meant when somebody hit a bad note singing harmony, you’d wop ’em.”

Eventually, the notorious Detroit Police “Big Four” unit would arrive to break up the “disturbance,” and not always pleasantly. Incensed by this treatment, Reeves’ father, Elijah, and another neighborhood dad appealed to the City Council for relief. Surprisingly, the Council granted them permission to block off a small section of Riopelle every Saturday night so the neighborhood teens could sing and dance freely from sunset to midnight.

So, yes, that means Martha, her family, and friends were all … dancing in the street!

She couldn’t possibly have known her dad’s bold gambit would produce the title of one of her greatest Motown Records hits with the Vandellas in 1964. Or could she?

Reeves says her aunt Bernice offered visions of her future early on. “She pierced my ears and prophesied,” she recalls. “She told me at age 11, ‘You’re going to be famous one day. You need to call yourself ‘Martha LaVelle.’”

She might have been at least half right about that sultry stage name, too, as we’ll explain later. As far as Reeves’s own predictions went, however, she missed one by a Motown mile: “I thought I wouldn’t be here past 35.”

She was off by 45 years and counting. And now, as her close friends and relations prepare to serenade her on her 80th birthday (it’s July 18) with a lavish, invitation-only soirée in Detroit, Reeves is taking time to reflect on her journey so far. “The route leading up to 80 has been really rough,” she says, “but I’m glad to see it.”

She’s seeing it, yes. But she’s seeing it through a fog these days — and that has absolutely nothing to do with the passage of time.

“I’m sort of messed up now because the COVID, pandemic, or whatever you want to call it, has put me in a twilight zone,” she says. “I feel like I’m living in a science-fiction movie. As everything is so strange, I’ve still been getting over 10 fan letters a week, so people haven’t forgotten. Most of them just want free pictures, or for me to autograph pictures they took off the internet.”

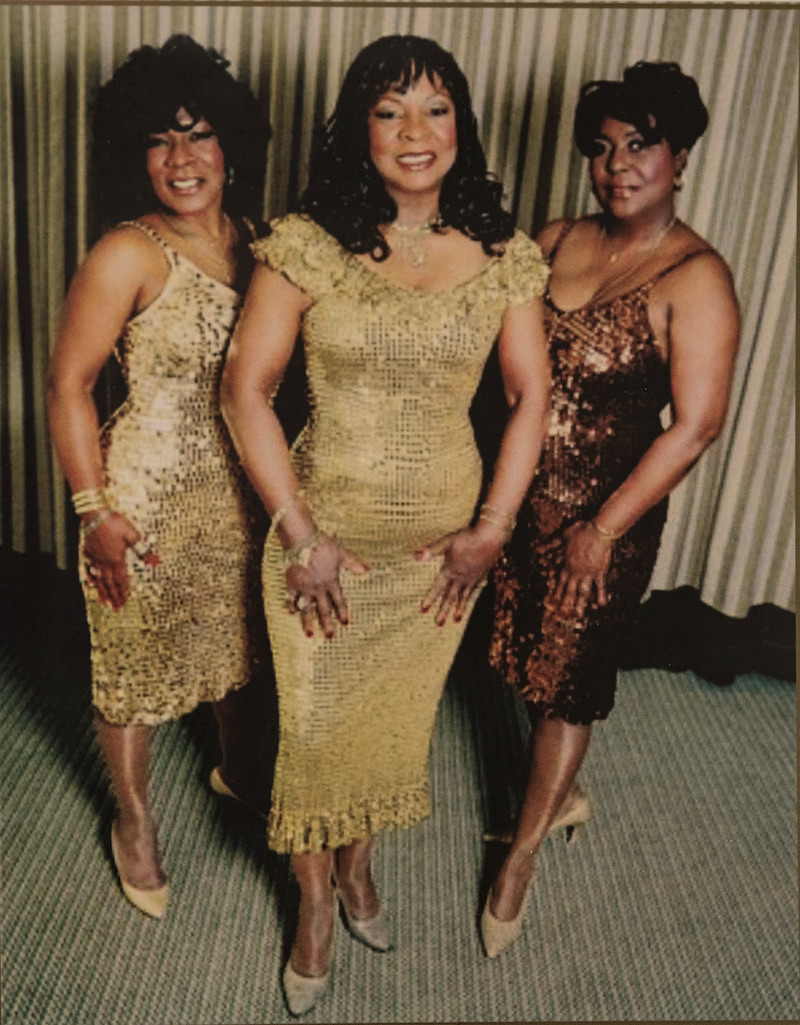

As fellow Motown immortal Abdul “Duke” Fakir lamented in a 2020 interview with Hour Detroit, the coronavirus deprived many popular musical acts of their prime source of relevance and revenue: touring. “I employ eight people,” Reeves says, including her sisters Lois and Delphine as the current Vandellas. “It’s very discouraging.”

“We were going to China! We had gigs planned for England. Six months of planning canceled in a day, just tossed into the shredder. It was mind-blowing for the world to just stop like that. I hope that everybody gets their shot. Somehow we have been blessed to hold on and plan to work this year.” Dates are slowly being booked for the latter half of 2021.

And that’s a very good thing, because the sad reality is that we are slowly losing our divas. Aretha, of course. But the sudden death of original Supreme Mary Wilson in her sleep on Feb. 8 rocked the Motown family and the pop music world at large. Reeves took the loss particularly hard since she and Wilson, a fellow Northeastern High School alum, had performed together on numerous occasions over the past 10 years as The Legendary Ladies of Motown.

“We toured all over the world,” Reeves recalls, making no attempt to hold back the tears. “We were very close. I loved her dearly. I wanted us to sing, ‘Mary, Don’t You Weep (Oh, Martha, Don’t You Moan),’ the Aretha Franklin version [from her Amazing Grace live LP], and I’ve got a letter that Mary wrote to me that said, ‘Yes, we will sing that.’ I’ve got it in my scrapbook now.

“I got over 100 calls the day she passed. The first set of calls offered condolences, but the next bunch were people asking, ‘What was she like?’ ‘Did you have a camaraderie?’ ‘Were you adversaries or good friends?’ I tried to answer all of them, but it almost made me sick, the ignorance. People who think we were all enemies at Motown. We were made together. We all loved like sisters. I miss Florence [Ballard, of the Supremes]. I miss Mary Wells. A lot of us are gone.”

But not our newest octogenarian, made-by-Motown local legend Martha Reeves, who could outlive us all. She has been ours since she and her family made the great migration from tiny Eufaula, Alabama, to join her grandfather, the Right Rev. Elijah Reeves of Metropolitan A.M.E. Church in Detroit, in search of a brighter future.

You may already know all or part of the backstory: Reeves gained her love of music early on from her mother, Ruby, and from her guitar-playing father, and later learned poise and presence from the fabled Motown etiquette coach Maxine Powell. After winning singing contests at the Graystone Ballroom and other local stages — yes, performing as Martha LaVelle — she landed a gig singing during happy hour at the old 20 Grand nightclub. She was heard there by William “Mickey” Stevenson, the dapper young A&R executive for Berry Gordy’s then-fledgling Motown record label.

“This good-looking man, he was finer than anyone I ever hit on,” Reeves recalls with a laugh. Stevenson gave her his business card and invited her to come down to Motown’s West Grand Boulevard headquarters and audition sometime.

Viewing that card as her Willy Wonka golden ticket, Reeves raced down to Motown the next morning, blew past the line of hopefuls, and insisted upon seeing Stevenson. A shocked Stevenson asked her to sit at a desk and answer phones while he took care of some business.

He left her there. She didn’t leave. Reeves went on to make herself indispensable in the A&R department — under her real name — and whenever a singer missed a recording session or an extra voice was needed for harmony, like for that dashing up-and-comer Marvin Gaye, she would race into Studio A within seconds.

“I was not a secretary,” she has often said. “I was a singer who could type.”

Persistence pays. When Mary Wells couldn’t make a session one day, Reeves quickly called her vocal mates Rosalind Ashford and Annette Beard, with whom she had been performing around town as the Del-Phis and later the Vels, and told them to come running. Their collective talent impressed Gordy enough that he signed them to a contract in 1963, renamed them Martha and the Vandellas, then applauded his decision as a string of hits — “Come and Get These Memories,” “Dancing in the Streets,” “Nowhere to Run,” “Jimmy Mack,” and the million-selling “(Love Is Like a) Heat Wave” among them — ensued.

The Vandellas have undergone numerous personnel changes over the decades, but Reeves has remained the constant star presence, catapulting the group into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Her desk remains a prominent part of the exhibits at Detroit’s Motown Museum to this day.

She moved to Los Angeles for 14 years upon the expiration of her Motown recording contract and released albums on MCA Records and several other labels, but moved back to Detroit when both of her parents fell ill, and reclaimed the city as her home.

Along her journey she gave birth to a “love child,” Eric (“I asked for a baby, not a man, and that’s what God gave me,” she says), now a successful labor executive. She was introduced to cocaine by her LA dentist, attempted suicide, and was born again through the guidance of LA minister the Rev. E.V. Hill. “He baptized me and told me God loves me and has a plan for my life,” she says. “I didn’t know that until then.”

Over eight decades, Martha Reeves has become deeply ingrained in the fabric of Detroit. As a natural headline magnet — not always for the most positive news — she so engages Detroiters that when she ran for a seat on the Detroit City Council in 2005 with virtually no political experience, she was elected to a four-year term — her “second job,” as she refers to it.

“That’s a part of my life that I want to give back,” she says with a laugh. “Because they scrutinized me, they followed me around. I’ll never forget, an investigative TV reporter from Detroit came all the way out to San Francisco, where I was performing. We were on recess at the time, and I had to keep doing gigs because I couldn’t afford to live if I had to depend on the little money they pay the City Council every two weeks.”

“So, I was in my meet-and-greet line after the show and this man ran up into my face with a microphone and said, ‘Do you think you should be here in San Francisco having this much fun while Detroit is suffering an economic crisis?’ I said, ‘We’re on recess.’ But he asked the question again. Finally, I just said, ‘This, too, shall pass,’ and walked to my dressing room.

“They put me under such scrutiny. They didn’t catch me in somebody’s house with their husband, they didn’t catch me in a drug den. I was just trying to entertain my fans and make a living. They always made it seem like I was doing something wrong.”

She left the council after a single term, but thankfully city government isn’t where her legacy rests. Martha Reeves became a breakout Motown diva years before Diana Ross and gave the label its first Grammy nomination, and her urgent, gospel-powered vocals will be part of pop music history forever.

“They called it ‘The Sound of Young America,’ but we made the sound of America, England, Europe, and every other place where we were known,” she says. “Our music has been glorified, and I’m so excited. I’m thrilled. Berry Gordy, I praise him, because had it not been for him, I never would have been famous.”

Aunt Bernice might disagree.

|

|

|