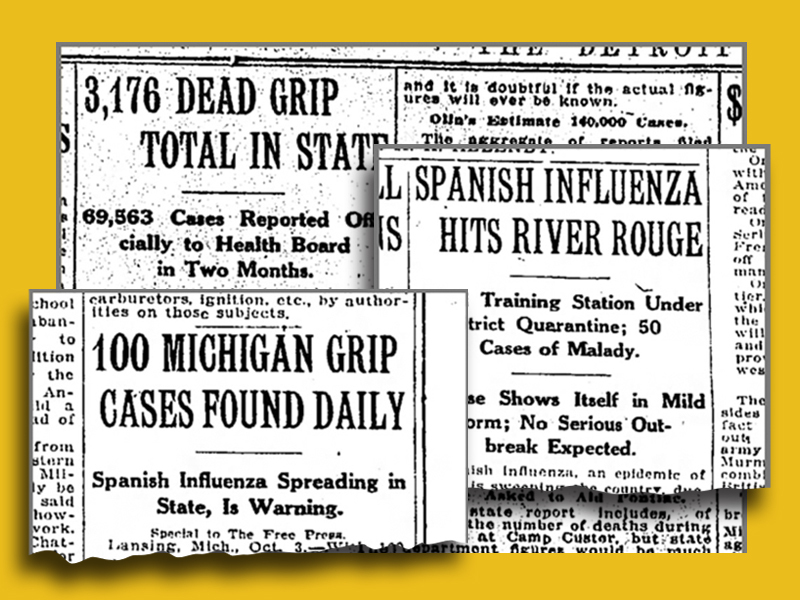

As World War I raged, Michigan newspapers chronicled another worldwide scourge: the deadly 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Here’s a look at how the virus affected the state.

Aug. 14, 1918

The Detroit News’ first report of a Spanish flu case related to a Michigander features Lt. Ralph M. Rowland of Lansing, who had the disease in France and “was carried on his cot to the front-line trenches where he directed his men in an attack which drove off the Germans.”

Aug. 27, 1918

As health officials begin sounding warnings about close contact, a Detroit Free Press writer reports — under the byline Phelan Fyne — that “not all the scare starters in the world can make us kiss through handkerchiefs or wire screens or any other impediments. The undraped smack is a human right.”

Sept. 14, 1918

The first reference to the Spanish flu as a “pandemic” appears in the Free Press, albeit in a report from Washington, D.C., about cases in Alabama, New York, and Philadelphia.

Sept. 18, 1918

The Free Press reports that, “where the disease has appeared cases have been numerous but the mortality is low.”

Sept. 23, 1918

As many as 50 cases of Spanish flu are diagnosed at the Naval Training Station in River Rouge, prompting a quarantine. The disease may have been the result of “scattering of germs by enemy spies,” the Free Press reports.

Sept. 25, 1918

Some 30,000 cases are diagnosed in U.S. Army camps, including 155 deaths, according to a wire service report in the Free Press. “More favorable weather conditions were expected to aid materially in stamping out the malady in its first stages.”

Sept. 27, 1918

State public health authorities order “private funerals” for casualties of the Spanish flu to stem its spread, the Lansing State Journal reports.

Sept. 30, 1918

Camp Custer, near Battle Creek, is quarantined after 557 patients with Spanish flu are admitted to the base hospital in one day. “Athletic activities so far have only been cut down,” not halted, LSJ reports. In New York, officials seek volunteers to “relieve the shortage of nurses and orderlies in hospitals.”

Oct. 2, 1918

The first six cases in Detroit are reported to the state health board. The health commissioner says two patients had just come from “eastern cities where there are outbreaks,” the Free Press reports.

Oct. 3, 1918

“Proof that the Spanish influenza is of German origin is not needed. None but a Hun would ever start such a disease,” the Free Press writes.

Oct. 9, 1918

With nearly 200 cases of Spanish influenza among the University of Michigan student army training corps, “Ann Arbor hospitals are filled to capacity,” LSJ reports.

Oct. 11, 1918

With 2,500 cases logged in the state, Gov. Albert Sleeper calls for a voluntary cancellation of public meetings.

Oct. 12, 1918

A front-page report in the St. Joseph Herald-Press calls the Spanish flu “nothing new” and urges people who feel ill to “go to bed and stay quiet — take a laxative — eat plenty of nourishing food — keep up your strength” and says “nature is the cure.”

Oct. 16, 1918

Facing a medical personnel shortage, the state board of health releases the senior class of medical students at U-M and University of Detroit to care for patients, the Free Press reports.

Oct. 19, 1918

“Within 24 hours, there have been 45 deaths, bringing the total since Sept. 28 to 165. This is the highest record for fatalities in a day since Camp Custer was built,” the Free Press reports.

Oct. 19, 1918

Gov. Sleeper orders the shutdown of “theaters, movies, churches, lodge meetings, political gatherings and all gatherings which can legitimately be construed as non-essential,” the Free Press reports. Schools remain open.

Oct. 22, 1918

Detroit schools are closed, and 56 deaths are reported in the city. Nearly 3,000 teachers are reassigned to “work visiting homes of influenza sufferers and advising in their care,” the Free Press writes.

Oct. 24, 1918

Michigan reports 50,000 cases and 134 dead. Charlevoix bars visitors. Owosso casket makers “can’t keep up with orders,” the Free Press writes.

Nov. 4, 1918

The Free Press speculates about how a ban on “all public meetings because of the pandemic of Spanish influenza” would impact that day’s midterm elections: “[B]oth parties resorted to newspapers, billboards and tons of literature to carry their messages to the electorate.”

Nov. 7, 1918

Fewer than 350 new cases are reported to the state in one day. The governor’s closure order is to be lifted on Nov. 8, the Free Press writes.

Nov. 12, 1918

A letter-writer to the Free Press asks if eating “small pinches of salt” will cure or prevent the disease. The reply: “Its prevention consists of keeping outside of a five-foot barrage of anybody with an apparent ‘cold’ and masking every such person. Salt, camphor, onions, asafetida and all such tommyrot will prevent about as much as a rabbit’s foot.”

Nov. 14, 1918

“Spanish influenza, which a few days ago was generally supposed to have passed its high point in Michigan, is increasing again,” the Free Press writes after 689 new cases are reported. “Some state authorities blame it on peace celebrations.” (Germany had surrendered on Nov. 11.)

Dec. 1, 1918

The Free Press reports a death toll of 3,176 out of nearly 70,000 cases reported since October, but because of incomplete record-keeping, “it is doubtful if the actual figure will ever be known.”

Dec. 6, 1918

With more than 1,500 new Spanish flu cases reported in Michigan, the governor considers another mass closure as “a last resort.” A Free Press headline declares Spanish flu “more deadly than war.”

Jan. 12, 1919

“Spanish influenza as an epidemic seems to have passed in Michigan,” the Free Press reports. New cases had hit 321, the lowest daily tally since the outbreak officially started on Oct. 1, 1918.

Jan. 25, 1919

Another wave of the disease will spread “unless strenuous measures are adopted,” the state’s health director says. A resurgence is blamed on the “relaxation of quarantine regulations at the bottom of the latest outbreak.”

Sept. 13, 1919

“There should be no repetition of the extensive suffering and distress which accompanied last year’s pandemic,” the Port Huron Times-Herald writes. “The prompt recognition of the early cases and their effective isolation should be aimed at.”

Feb. 4, 1920

A resurgence of cases prompts the Free Press headline: “Spanish Influenza is Epidemic Here.”

|

|

|