When you’re a kid, you’re always someone else. In the summer of 1968, metro Detroit’s neighborhoods were filled with pint-sized Al Kalines, Denny McLains, and Willie Hortons. One of those young wannabes was 7-year-old Elyse Summers, whose imitation of Dick McAuliffe’s distinctive “foot-in-the-bucket” batting style was a homage to the Tigers’ All-Star second baseman.

“I’m not sure how well I pulled it off,” says Summers, today a lawyer in Maryland. “He batted left-handed and I was right-handed.”

It didn’t really matter, as the Oak Park schoolgirl’s true favorite was Horton. “Willie embodied that team better than anyone,” she says. “He was a Detroiter, through and through.”

A legend on local sandlots and a fixture in Tigers lore, Horton has been rewarded with a sculpture at Comerica Park and a warm spot in the city’s heart. As the first black Tiger to achieve stardom, his potent home-run bat inspired shouts of “Hit the ball, Willie!” from fans of all colors. When the city erupted in murderous unrest in July 1967, the husky left fielder visited the riot area and pleaded for calm.

“When you grow up in the city like I did … the culmination of all that was almost overwhelming.”

— Tiger catcher Bill Freehan

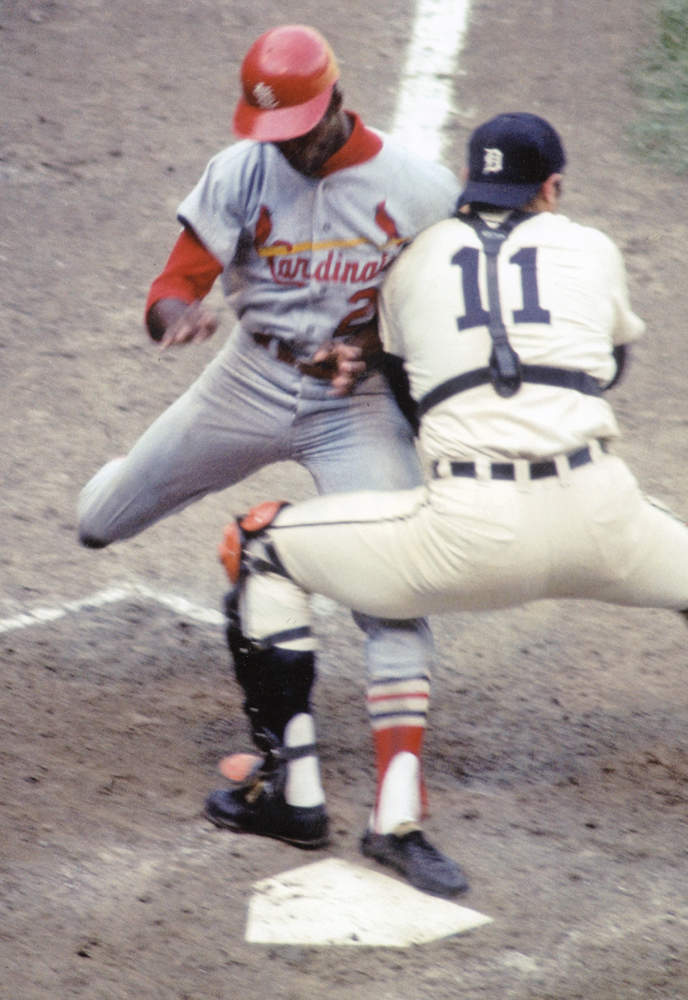

Horton hit a career-best 36 homers in 1968, but it was a single defensive play for which he is best remembered. In arguably the pivotal moment of the ’68 World Series, his throw to the plate snuffed out a sure run and shifted the momentum from the confident St. Louis Cardinals to the wobbly Tigers.

Fifty years on, simply uttering the words “the ’68 Tigers” to people of a certain age can trigger a stream of random images, all pleasant. Mickey Lolich, the self-styled “working-class pitcher,” pulling up to the ballpark on one of his five motorcycles. Chunky Gates Brown winning both games of a twin bill against Boston with pinch-hits. Don Wert’s pennant-clinching single against the Yankees setting off a spectacular Hudson’s fireworks show in center field. José Feliciano lighting up the Tiger Stadium switchboard — pro and con — with his bluesy and decidedly nontraditional rendition of the national anthem before Game 5 of the World Series.

It was a season that enthralled the baseball world while applying some badly needed balm to a community still reeling from the previous summer’s riot. Horton, for one, felt that the team was on a mission. “I believe the ’68 Tigers were put here by God to heal this city,” he said at the time.

A Team on a Mission

The feel-good story of the ’68 Tigers actually begins on the final afternoon of the 1967 season. Playing on a wet and gloomy Sunday inside a half-filled ballpark, the Tigers ended an incredibly tense four-team race by dropping the second game of a must-win doubleheader. Afterwards, hundreds of fans tore up the Tiger Stadium turf, ripped out seats, and climbed the screen behind home plate.

The players were just as frustrated by their near-miss of the pennant, with one angrily firing a ball at a reporter as he trudged into the clubhouse. “I was so upset that we didn’t win,” said another. “We had the best team. But we didn’t win.”

At Lakeland, Fla., the following spring, batboy Rick Miller marveled at the players’ focus, as well as their creative vocabulary. “McAuliffe, Ray Oyler, Dick Tracewski — they were little guys, but they were pretty intense,” the Arizona retiree says today. “They’d slam their bats into the ground and they cussed like sailors. I learned some new words from those guys.”

Miller, then a gangly Catholic schoolboy, had a favorite Tiger: Bill Freehan, who as a youngster in the ’50s had cheered on his home team at what was then called Briggs Stadium. In 1968, the perennial All-Star catcher uncomplainingly took a beating behind the plate and at bat (he set a league record for getting hit by pitches) while finishing runner-up for the American League’s Most Valuable Player Award.

“You’d see him at mass every day before home games at Lakeland,” Miller says. “The rest of us were just kids, the nuns, and some old people. Freehan was 6-2, or 6-3, 200 pounds, so he really stood out in church.”

The prayers of the long-suffering were answered, as the Tigers climbed into first place in early May and never looked back.

“We were a special group, those Tigers,” Gates Brown once reflected. “We played hard, we fought hard, and we partied hard, but when we got in that uniform between the white lines it was all business. We put our differences aside and we had one objective — and that was to beat the opposition in any way, shape, or form.”

Socking It to Them from Behind

Last-lick victories became the team’s trademark. Forty of their club-record 103 wins came when they were either tied or trailing from the seventh inning on.

“There was a different hero every game,” says broadcaster Ray Lane, who watched the magic unfold from the cramped booth behind home plate. “The big guys like Kaline, Horton, and Norm Cash came through. But you also had the bench warmers — guys like Tommy Matchick hitting a game-winning home run in the ninth, or Jim Price (now a radio color commentator), coming up with a big hit. The Gator had a great season as a pinch-hitter. Everybody was a star.”

Years before free agency turned rosters into an ever-changing carousel of mercenaries and strangers, the Tigers were a home-town team filled with familiar faces. Besides Freehan and Horton, several other players, notably Mickey Stanley and Jim Northrup, were “Made-in-Michigan” products. Most others were Midwesterners who had come up together in the Detroit team’s farm system. Longtime favorites Kaline and Cash — who hailed from Baltimore and Texas, respectively — were so closely identified with Detroit they may as well have been named Vernors and Faygo. The veteran Kaline was in his 16th season and had purposely avoided watching the World Series during his long career. The first one he would see, he insisted, would be the one he finally played in.

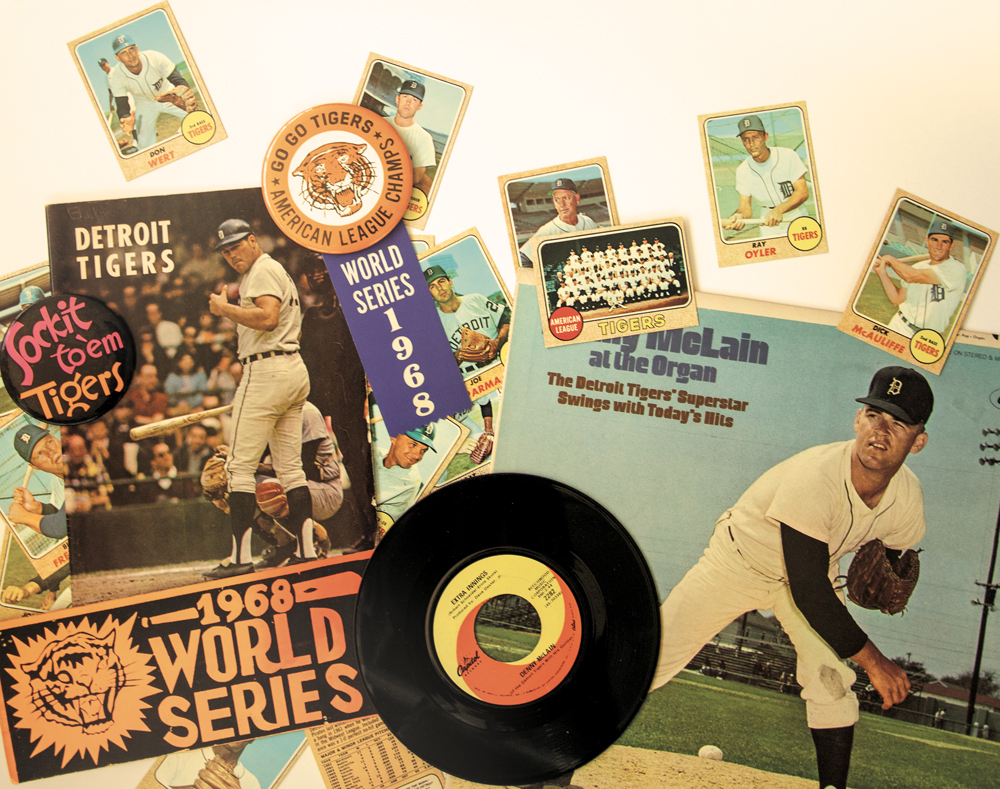

A club-record 2 million-plus people (2,031,847 to be exact), packed Tiger Stadium’s signature green stands in 1968. No team in the majors drew more fans or was more closely embraced by the community. Local media appropriated the “Sock it to me” catchphrase from a new show on NBC, Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In. “Sock it to ’em, Tigers” appeared everywhere: songs, signs, commercials, and bumper stickers. It was spoken or written in a multitude of languages, including Hungarian (Verd neg oket Tigerish), Yiddish (Dalaing iss tze zayTigers), Polish (Die che eem tgrysy), and Japanese (Bonzai, Tigers).

The sock-it-to-’em Tigers were different from all previous Detroit championship teams. For the first time, a pennant winner reflected the racial composition of the city, which was now nearly half black. Prior to 1968, the Tigers had won seven pennants and two World Series, the last in 1945. All came during baseball’s apartheid era.

In 1968, the Tigers — who a decade earlier were the second-from-last big-league club to desegregate — had six black athletes among the 33 men who played that season. White or black, many on the team sank roots in the area and never left.

Music to Fans’ Ears

Legendary radio and television broadcaster Ernie Harwell’s Southern-inflected voice was ubiquitous. With only one quarter of the team’s schedule televised, fans in this pre-cable era were more accustomed to listening to the game than watching it, Summers says. “People sitting on their porch, in the backyard, in cars, in stores — wherever you went, you heard Ernie on the radio. You could probably walk around the entire neighborhood and not miss a pitch.”

If Harwell’s play-by-play was that summer’s soundtrack, organ accompaniment was provided by Denny McLain, who racked up an astonishing 31-6 record and remains baseball’s only 30-game winner in the last 84 years.

“Denny was my man,” Brown once said. “I mean, I loved him. It was the way he wore his hat and he had that nice high leg kick, everything was over the top — I mean, the man was cool.”

At 24 years old, the fastballer was cocky, flamboyant, and great copy. He played his Hammond X-77 organ in nightclubs and at store openings, drank 25 bottles of Pepsi a day, and was an early proponent of what we now know as “alternative facts,” rearranging the details of a story to fit the person or the occasion. He appeared on the cover of Time and other national magazines and hobnobbed on TV with Steve Allen, Ed Sullivan, and the Smothers Brothers.

Impish and impulsive, McLain breezily bent the rules as only a spoiled superstar could. One Sunday in July, he beat Oakland in the first game of a doubleheader at Tiger Stadium, then climbed into the organ loft during the nightcap to entertain fans with his version of “Satin Doll.” Later, he almost missed a start against Cleveland, racing to the park from a recording studio on Livernois, where he had just finished cutting an album for Capitol Records: Denny McLain at the Organ: The Detroit Tigers’ Superstar Swings with Today’s Hits. McLain beat Cleveland and all was forgiven.

Impish and impulsive, McLain breezily bent the rules as only a spoiled superstar could. One Sunday in July, he beat Oakland in the first game of a doubleheader at Tiger Stadium, then climbed into the organ loft during the nightcap to entertain fans with his version of “Satin Doll.” Later, he almost missed a start against Cleveland, racing to the park from a recording studio on Livernois, where he had just finished cutting an album for Capitol Records: Denny McLain at the Organ: The Detroit Tigers’ Superstar Swings with Today’s Hits. McLain beat Cleveland and all was forgiven.

When hardware was handed out at season’s end, he was voted the league’s MVP and was the unanimous choice for the Cy Young Award as the league’s top pitcher.

McLain was nicknamed “Dolph” because his face resembled a dolphin’s and he was considered a “fish” at poker and pinochle. “We took all his money,” Northrup said in a 2008 interview.

“Once during the ’68 season, we got into a fight in a card game. … Gates Brown grabbed me and damn near killed me. I said, ‘That SOB was trying to steal my money,’ and Gates said, ‘I don’t care, I’m going to protect him because he’s gonna take us to the pennant.’ ”

McLain’s roommate was shortstop Ray Oyler. An excellent glove man, the hard-drinking ex-Marine fielded an endless stream of phone calls from promoters, reporters, and celebrities, all hoping for a moment of McLain’s time.

“Is this the superstar?” a caller would ask.

“Speaking,” Oyler would say.

Managerial Decisions

Oyler batted a woeful .135 in 1968, causing manager Mayo Smith to make one of the boldest gambles in World Series history. He benched Oyler and installed Stanley, the regular center fielder, at shortstop. This allowed Kaline, who Smith struggled to fit into the everyday lineup after an injury early on in the season, to return to right field. Northrup replaced Stanley in center.

The moves paid off. Stanley made just two harmless errors while Kaline and Northrup contributed clutch hits.

The Tigers were underdogs against the Cardinals, a talented squad gunning for its third championship in five seasons. In the opener at Busch Stadium, the ornery and overpowering Bob Gibson registered his 13th shutout of 1968 and a Series-record 17 strikeouts with a 4-0 masterpiece. It didn’t help that McLain was up past midnight entertaining star-struck guests inside a hotel lounge, with Northrup merrily serving as emcee.

After the Tigers rebounded with an 8-1 win to knot the Series, St. Louis humiliated Detroit in the next two games at Tiger Stadium, 7-3 and 10-1. This gave them a commanding 3-games-to-1 edge. Only two teams had ever overcome such a deficit in the World Series.

The Tigers seemed doomed. The mighty McLain had lost both of his starts, and the team had misplaced its mojo. When the Cardinals scored three runs off Lolich in the first inning of Game 5, all but the most die-hard believers at Tiger Stadium that chilly Monday afternoon abandoned their championship hopes. “I figured it was all over,” Lane admits. “It had been a great season, but I’m thinking, ‘Cardinals win the Series in five.’ ”

But the Tigers clawed their way back. The turning point came in the fifth inning, with St. Louis trying to build on its early lead. Lou Brock, a speedster who bedeviled the Tigers all Series, unaccountably failed to slide as he tried to score from second base on a single to left. Horton uncorked a perfect throw home. Brock’s foot was a tantalizing half-inch from the plate when Freehan sent him spinning with a shoulder block and applied the tag. Two innings later, Kaline’s two-run single was the key hit as the Tigers rallied for a 5-3 victory.

The Series shifted to St. Louis. Given new life, the Tigers crushed the Cards, 13-1, as McLain finally returned to form and Northrup hit his fifth grand slam of the year.

This set up the showdown on October 10 between Lolich and the seemingly invincible Gibson. Both were aiming for their third win of the Series. Gibson, who had won the deciding game in each of his two previous World Series, was the best money pitcher on the planet. The Baseball Hall of Fame, anticipating the result, had already asked for his glove.

What’s Better Than Game 7?

Despite the made-for-primetime drama, Game 7 was played on a Thursday afternoon. Baseball was still a game of tradition in 1968, and the World Series continued to be played in the sunlight. Summers remembers a TV being rolled into her classroom, a scene repeated in countless schools, offices, and shops.

Lolich, pitching on just two days’ rest, worked carefully. Twice he picked runners off first base. The game remained scoreless until the seventh inning when, with two runners on, Northrup slammed a drive to center that Curt Flood misjudged. The ball sailed over Flood’s head for a triple, and the Tigers had finally broken through. Before the inning was over, they had scored three times.

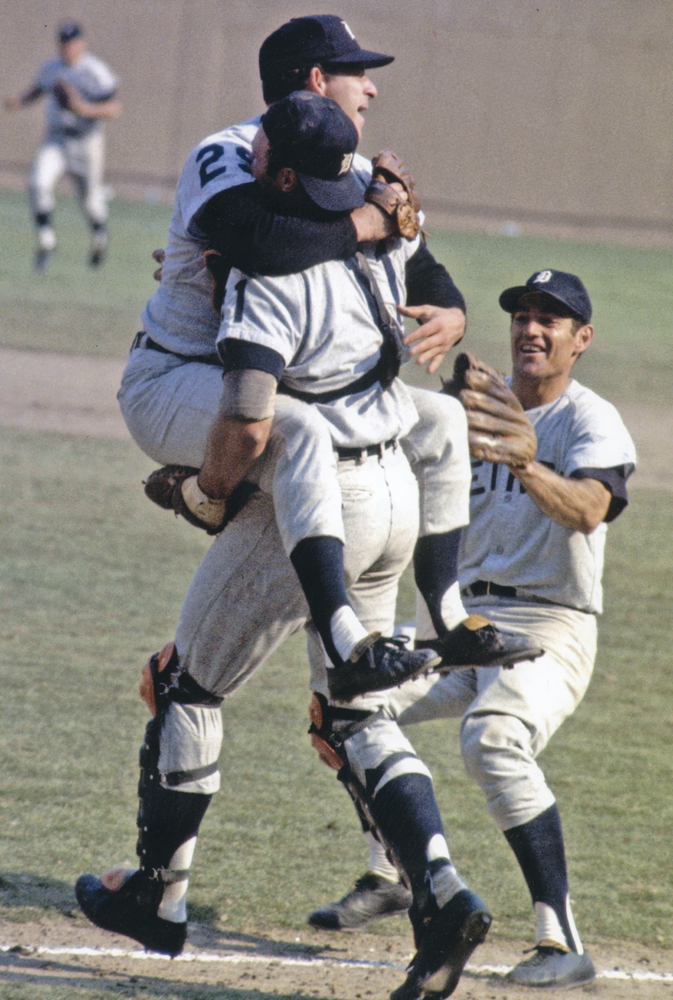

It was 4-1 in the bottom of the ninth when, with two outs, Lolich induced Tim McCarver to lift a foul fly. Freehan always relished recalling the exact moment — 4:06 p.m. Eastern time — when he squeezed his mitt shut on McCarver’s pop-up. “When you grow up in the city like I did and used to hitch-hike down to Briggs Stadium and sit in the bleachers, the culmination of all that was almost overwhelming,” he said.

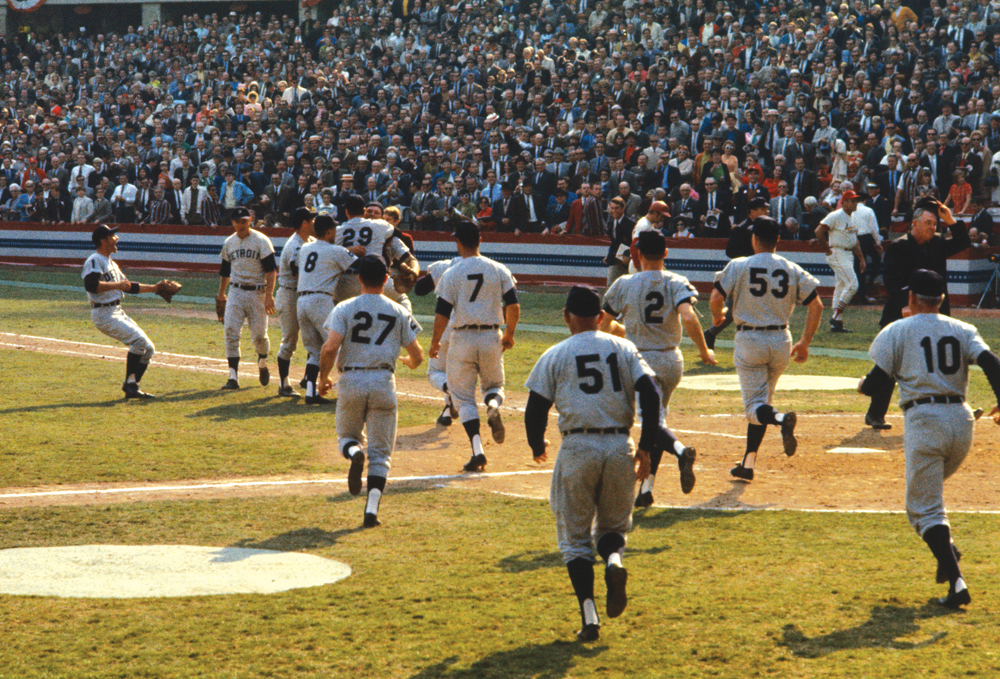

Lolich, named the Series’ MVP, leaped into Freehan’s arms — and almost immediately began referring to himself in the third person. “Mickey Lolich has never been a hero with the Tigers,” he said afterwards. “Mickey Lolich has always been a number on the roster. Finally, somebody knows who I am.”

Back in Motown, exuberant fans behaved like Martha and the Vandellas — dancin’ in the streets. Downtown was alive with honking cars, fluttering confetti, and office workers boogying on the sidewalks. Civil defense sirens wailed and fire trucks, loaded with fans, rumbled through the littered streets.

“Mickey Lolich has never been a hero … Finally, somebody knows who I am.”

— World Series MVP Mickey Lolich

In the city’s neighborhoods, some youngsters emulated their champagne-spraying heroes by joyously showering each other with shaken bottles of pop. That evening, around 35,000 fans swarmed Detroit’s Metropolitan Airport, forcing the team plane to divert to Willow Run in Ypsilanti, where it was greeted by several thousand other celebrants.

It was wild, it was wonderful, and for many aging Detroiters, the afterglow has never completely dissipated.

“It was just an unforgettable year, with players who were our heroes but also very relatable,” Summers says. “It was the season that totally drew me in, and I’ve been a die-hard fan ever since.”

Two Tycoons, But No Millionaires

This year, the average major leaguer will make $4.52 million in salary, not including any postseason checks. Ballplayers 50 years ago could only dream of such riches, but they still did OK. “When you make $65,000 a year,” The Sporting News noted in 1968, “you tend to be classified as a tycoon.” By that yardstick, the ’68 Tigers had two “tycoons.”

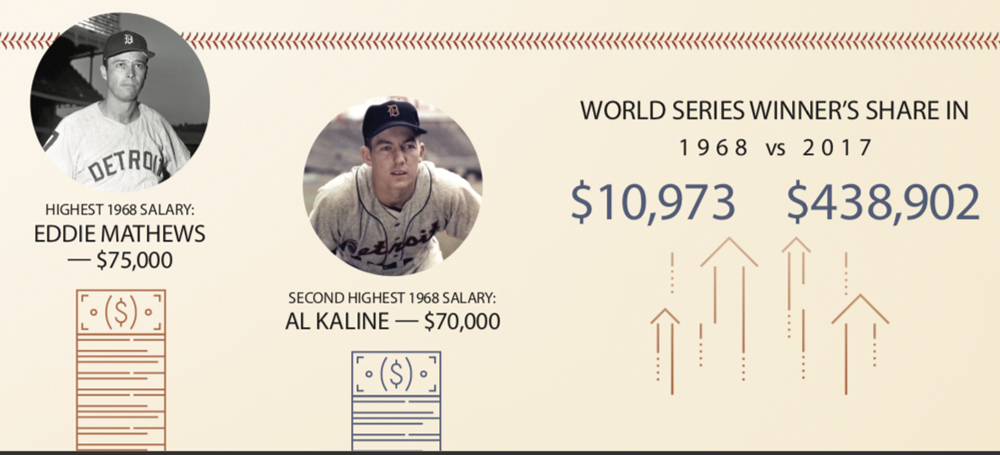

One was perennial All-Star Al Kaline, who was paid $70,000. The other was back-up third baseman Eddie Mathews, then in the twilight of a career. Because veterans’ salaries then were based as much on seniority as performance, Mathews actually was the highest-paid Tiger at $75,000.

In a year when a first-class stamp was 6 cents, a box seat at Tiger Stadium cost $3.50, and the medium household income was $7,743, these were not inconsiderable amounts. Adjusting for inflation, Mathews’ and Kaline’s salaries were each worth slightly more than $500,000 in today’s dollars. Most salaries ranged between $25,000 and $50,000. In addition, each Tiger on the roster received a winner’s share of $10,937.

The numbers all seem so quaint now. Last season, Houston received World Series payouts of $438,902 per man — pocket change for Astros ace and ex-Tiger Justin Verlander, whose season salary is an otherworldly $28 million!

|

|

|