On April 8, 1956, Detroit held a parade — a funeral procession more like it — to mark the death of the city’s streetcars. Late that afternoon, the last streetcar in the procession, car No. 237 — a banner reading “The Journey’s End” hanging from its rear — pulled into the Woodward Carhouse, bringing an end to 93 years of street-rail service in the city.

As a young man, Elmore Leonard says he rode Detroit’s streetcars every day. The prolific novelist and screenwriter moved to the city in the late 1930s, when the price of a ride was 7 cents. “Before [World War II], my friends and I would hop on a streetcar and go downtown,” Leonard, 86, recalls. “We would go to the Vernor’s plant for free samples of ginger ale. Then we’d go down to the waterfront and hop a ferry to cross the river to Canada, which cost a nickel. You could really have a lot of fun on 12 cents.”

Best of all, you didn’t need a car to get around — “unless you had a date,” Leonard says, admitting that he took one of his first on a streetcar.

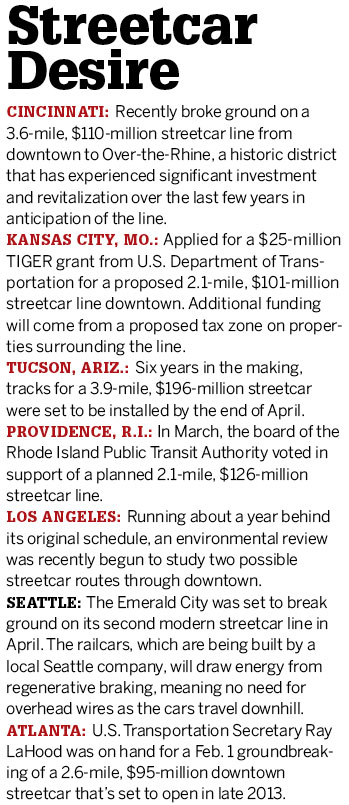

Although the prospect of getting to downtown and Canada on 12 cents belongs to a bygone era, streetcars are enjoying a national renaissance, thanks to their role in spurring economic development in Portland, Ore., and Seattle. Now, several American cities are hopping aboard the streetcar bandwagon. That includes Detroit and its M1-Rail project. “We’re going back to the future,” M1 CEO Matt Cullen says about possible streetcars along Woodward between Midtown and downtown.

When M1 started three or four years ago, we were proposing to do a streetcar system for 3.4 miles in the heart of downtown, surrounded by bus rapid transit; that was our original plan,” says Cullen, who is also CEO of Rock Ventures, an umbrella entity that helps manage Dan Gilbert’s portfolio of companies and investments, which now includes nine downtown buildings.

Originally announced in 2008 as a $103-million curbside light-rail loop along Woodward, the private nature of M1 allowed it to be fast-tracked for completion by late 2010 with little red tape. But before much progress could be made, M1 became entwined with two related public rail projects from the Detroit Department of Transportation (DDOT) and the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT). The consortium of private investors behind M1, headed by Gilbert and auto-racing executive Roger Penske, agreed to throw its support behind DDOT’s Woodward light-rail project, using the private money as matching funds for federal dollars.

The once relatively modest private project ballooned into one with a $600-million price tag. After years of wrangling with the very bureaucracy M1 originally set out to avoid, the light-rail option was scrapped last December in favor of a rapid bus system serving the tri-county region.

But the private M1 group refused to be derailed despite the setback. The project returned to square one, as a privately funded, 12-stop streetcar line on Woodward, from Congress to Grand Boulevard. At press time, M1 was in the midst of a 90-day review process to prove that the $130-million construction costs and $5-million yearly operating costs are valid projections that can be paid for. Cullen professed confidence in the plan’s economic viability and in Detroiters’ willingness to ride a modern streetcar, complete with onboard Wi-Fi, from downtown to the New Center by the end of 2014.

Some critics, the Cato Institute’s Randal O’Toole among them, deem streetcars too slow, clumsy, and expensive to make a real impact on a community. They also criticize streetcars for lacking the efficiency and flexibility of buses. “When operating in city streets such as Woodward, [streetcars] average less than 15 mph,” O’Toole wrote in a Detroit News op-ed piece last December. “Such slow speeds entice few people out of their cars.” O’Toole paints light rail as “an obsolete form of transportation” that “offers little congestion relief.”

Christopher B. Leinberger, a University of Michigan professor of urban planning and a visiting fellow at The Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., says O’Toole is missing an obvious point.

“In my mind, the reason you put in any transportation system is not to move people,” Leinberger says. “That’s not the goal. The goal is economic development. The means is by moving people.”

Transit, Cullen says, should actually increase congestion. “The broader goal of M1 is to create a much more vibrant, connected core at the center of the city of Detroit,” he says. “There’s a lot of good things starting to take place. But … the development along Woodward is kind of episodic. [M1] starts to encourage people to walk an extra block and check something out because they know they can hop back on the train.”

Although O’Toole disagrees, Leinberger says streetcars have proved to spur economic development. He has studied the impact of existing streetcar lines in Portland, Ore., and Seattle. “We saw, over a 10-year period, anywhere from a 50- to 500-percent increase in property-price valuation. It seems to be that the valuation increases take place in a uniform fashion up and down the streetcar line, two blocks on one side and two blocks to the other side.”

If that were to hold true in Detroit, then developers and landowners along Woodward stand to gain the most from it. And there’s nothing wrong with that, Leinberger says, because that’s how streetcar systems used to work. Before the rise of the automobile, when streetcars were the primary form of transit in a number of U.S. cities, most lines were privately owned and operated by the developers who owned land around them.

“That business model was put out of business by the federal and state government, who socialized transportation when they put in the roads,” Leinberger says. “These streetcars were built privately, operated privately, and many times they paid rent for the right-of-way, which was 30 to 40 percent of the city’s revenues.”

There’s a scandal referred to as the General Motors streetcar conspiracy — a sort of half-truth about how the automaker and others bought and dismantled streetcar systems around the county to replace them with buses. The U.S. Senate inquired into the matter in the ’70s, and the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit is loosely based on the alleged goings-on. Even those not prone to conspiracies can see that the automobile and the supportive government subsidies for auto-based development helped precipitate the decline in public transit across the country. After all, Leinberger says, at the peak of the Industrial Era, about 40 percent of all jobs were related to the automobile. “We — the people in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s — chose to subsidize low-density development, because as you were ‘seeing the USA in your Chevrolet,’ you were making yourself wealthier.”

That was, no surprise, especially true in the Motor City. On that topic, Leinberger doesn’t mince words: “How much longer do you want to keep on betting that the automobile is going to make and keep Detroit wealthy? Don’t put in rail transit, and you can continue to be a 20th-century economy.”

But will M1 succeed as a streetcar line? Leinberger guesses so, considering that it would link three “rather healthy places [downtown, Midtown, and New Center].” Would it be better off as true light rail? Cullen says the difference between the two is more like shades of gray, and M1 is prepared to do some shading, if necessary.

“What we’re designing now is a rail system that would allow for the larger light-rail cars to be on it later on, if there’s an expansion,” he says. “So it will not be a problem for us, if it extends in the future north of the Boulevard, which we hope it will.”

What rail transit does is help foster the most basic of transportation modes: walking, which creates a walkable urban place, as Leinberger calls it. Renewed interest in streetcars parallels a national trend back toward urban centers and away from the suburbs, which also parallels a demographic shift, he says. “It’s the aging of the Baby Boomers, but it’s more the burgeoning of the Millennials,” he says. “They were raised in the suburbs and they’re bored with the suburbs. They want a walkable, urban place” — even if that means walking backward in time.

If you enjoy the monthly content in Hour Detroit, “Like” us on Facebook and/or follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates

|

|

|