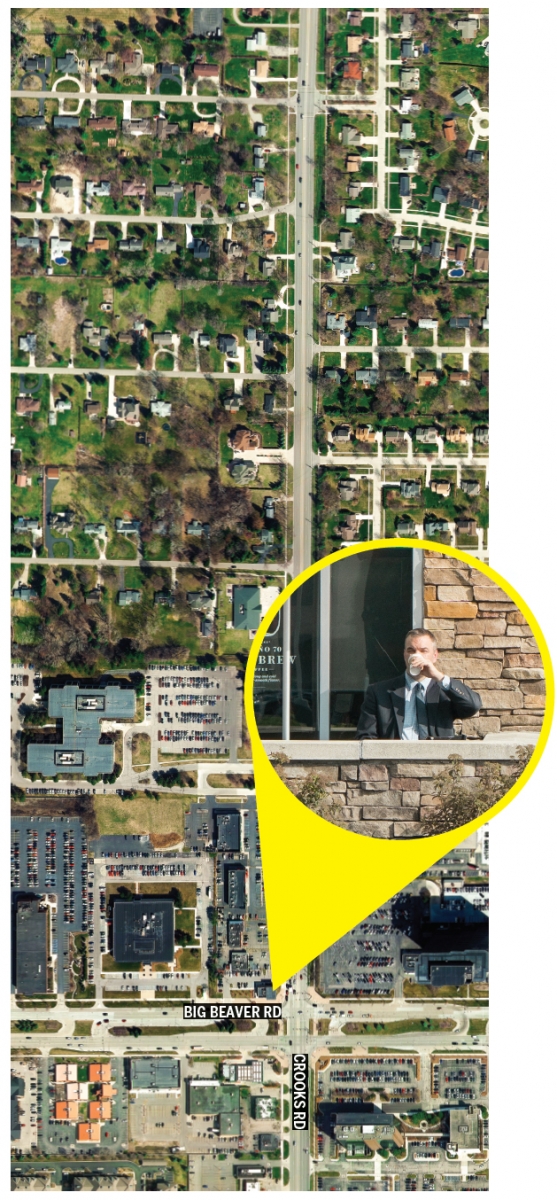

Brent Savidant has never eaten at a Chili’s nor Outback Steakhouse and sees no reason to start now. It’s an improbable streak, really, given that he lives in the Detroit exurbs (Clarkston) and works in the suburbs (Troy), where chain restaurants can feel like a way of life. But Starbucks — yes, the Troy city planner can live with that, and actually suggests the one at the suburban intersection of two busy surface arteries for an out-of-office interview. In fact, Savidant wants to show it off.

Brent Savidant has never eaten at a Chili’s nor Outback Steakhouse and sees no reason to start now. It’s an improbable streak, really, given that he lives in the Detroit exurbs (Clarkston) and works in the suburbs (Troy), where chain restaurants can feel like a way of life. But Starbucks — yes, the Troy city planner can live with that, and actually suggests the one at the suburban intersection of two busy surface arteries for an out-of-office interview. In fact, Savidant wants to show it off.

“I mean, going back 10 years, this site was a gas station,” he says, easing into a glass-half-full defense of the chain cafe’s existence. “And we’re sitting here on the patio, shooting the sh*t, watching the cars go by, and there are five people here enjoying the sunshine who could have sat inside. We’re still in Troy, and the automobile is a big part of what we are, but I’d say this works out here.”

At first, it’s difficult to see the coffeeshop as much of an upgrade of this corner’s social capital. For starters, it’s loud — so loud that Savidant’s argument often struggles to compete with the sounds of mid-day traffic. And the backdrop of strip retail, surface parking lots, and absence of foot traffic instantly undercut his pitch that this is a credible “third place” — a placemaking social hub that isn’t work or home.

But let Savidant finish his argument, and you start to see what he’s getting at. The Starbucks is in fact just a small, early part of an audacious retooling of Big Beaver Road — one that’s been in the works for more than a decade. So far, the city’s tried to soften the personality of the busy 200-foot-wide boulevard with bigger sidewalks for pedestrians and cyclists. They’ve revamped the zoning to allow the one-story strip retail to be gradually replaced with taller buildings, including apartments and condos, that are moved closer to the road, in an attempt to create a streetscape. They’ve even introduced a kitschy trolley system to add some public transit to the corridor. The transformation could take generations, but when it’s finished, the hope is that the makeover will give Troy something this sprawling, mid-century suburb never got around to building: a walkable Main Street — or at least something resembling one.

Savidant admits it’s been a tough concept for some to wrap their minds around. “You’ll never make Big Beaver walkable” has almost become a mantra among residents who hardly see the point in trying. Even if they pull it off, many doubt it will feel like an authentic downtown. But the idea of retrofitting suburban spaces to become more like cities is actually an experiment that’s playing out in communities all over the country. In general, these retrofits involve replacing the bread-and-butter forms of the postwar American suburbs (shopping centers, office parks, overbuilt parking lots, even cul-de-sac neighborhoods) with denser walkable areas that blend workplaces, housing, retail, and green space. It can scale big and small, and can take all kinds of forms: In suburban Denver, a developer created — from scratch — a downtown-like center on the site of a dead mall. In Washington, D.C., one of the fastest-growing metros in the country, planners are shooting to turn 80 million square feet of aging retail and parking lots into what would be America’s seventh-largest downtown — all anchored by a light-rail hub.

Such projects aren’t just suburban planners trying out trendy ideas. In many cases, they’re key parts of big-picture adaptation strategies — arguably urgent ones — that are borne of emerging social and economic forces. Suburbs like Troy have largely run out of the inexpensive vacant land that fueled their growth, so building anything new, by necessity, usually involves replacing something old. And the country is also on the cusp of several substantial demographic shifts that promise to reorder where and how we live.

In particular, an increasing share of baby boomers no longer see their four-bedroom, suburban empty nests as the ideal place to spend their retirement years (when compared to, say, two-bedroom downtown condos where somebody takes care of all the maintenance and you can walk to dining and shopping). And today’s 20- and 30-somethings, who, in general, prefer smaller-footprint housing that’s embedded in walkable communities, aren’t drawn to the car-fueled suburban dream like their parents were. Given these trends, demographers expect up to 85 percent of new American households in the coming years won’t have children in them. In Troy, two-thirds of its households are already childless, though this is due to its aging population more than an influx of young childless newcomers.

The implication is if single-family-home-dominated suburbs like Troy don’t adapt to what these two large demographics want, they could be passed over for other places in the coming years. Savidant, who’s not one for unnecessary drama, casts the issue with even more urgency. “With baby boomers getting older and household sizes getting smaller, we’re going to be at a point in the next 15 years where we have a dramatic oversaturation of large homes. And we have a lot of corporations who want to attract young employees, but those young people don’t want to live in Troy. They grew up in suburbs; they don’t want to be adults in suburbs. They want to go to real cities. So we have to evolve, or I think we die on the vine.”

The implication is if single-family-home-dominated suburbs like Troy don’t adapt to what these two large demographics want, they could be passed over for other places in the coming years. Savidant, who’s not one for unnecessary drama, casts the issue with even more urgency. “With baby boomers getting older and household sizes getting smaller, we’re going to be at a point in the next 15 years where we have a dramatic oversaturation of large homes. And we have a lot of corporations who want to attract young employees, but those young people don’t want to live in Troy. They grew up in suburbs; they don’t want to be adults in suburbs. They want to go to real cities. So we have to evolve, or I think we die on the vine.”

That Troy could be facing quite so stark a demographic crisis is not obvious today. By many measures, Troy is doing just fine: The city represents the third-largest tax base in Michigan, and the market for those four-bedroom homes is so strong, the crisis of the moment is tight inventory. Troy’s industrial sector is also booming, fueled by a recovery in the auto industry; and its office market, which hit 33 percent vacancy after the recession, has recovered faster than any suburb, with around 14 percent vacancy today.

Core Partners CEO and real estate adviser Matt Farrell, who recently helped the city analyze trends in its commercial, industrial, and office markets, says Troy still has a lot of strengths. Many of them are things that have always attracted people to the suburbs: good schools, excellent public safety, and shopping (the upscale Somerset Collection, he says, still ranks as one of the top malls in the country). But he buys Savidant’s argument about future demographic shifts, particularly because Michigan has essentially zeroed out when it comes to population growth. With that dynamic, he says, you could see a future that resembles a game of musical chairs in which you’re adding chairs instead of removing them.

Core Partners CEO and real estate adviser Matt Farrell, who recently helped the city analyze trends in its commercial, industrial, and office markets, says Troy still has a lot of strengths. Many of them are things that have always attracted people to the suburbs: good schools, excellent public safety, and shopping (the upscale Somerset Collection, he says, still ranks as one of the top malls in the country). But he buys Savidant’s argument about future demographic shifts, particularly because Michigan has essentially zeroed out when it comes to population growth. With that dynamic, he says, you could see a future that resembles a game of musical chairs in which you’re adding chairs instead of removing them.

“In places like North or South Carolina, where you have 7 percent growth, some want the new thing, but others are willing to backfill into the old thing, so there’s still a market for that,” Farrell says. “Unfortunately, that equation doesn’t work in southeast Michigan. So we add new buildings, new apartments; but without growth, we end up leaving something behind without a population to fall into it. There will be an empty chair in the room.”

It’s a process that’s arguably already underway. Many places are quickly adding to their density with new apartments, parking decks, and multi-story, multi-use buildings. But Farrell says that kind of reinvestment is unevenly favoring cities like Birmingham, Royal Oak, Ann Arbor, downtown Detroit, and other places with walkable urban centers. Developers in downtown and Midtown Detroit, in particular, can’t build apartments fast enough to keep pace with the demand; and vacancy in the city’s downtown office market is now at a decades-low 8 percent (compared to 14 percent in Troy). In more historic suburban cities like Berkley, Ferndale, and Royal Oak, the appetite for walkable places is even fueling a different form of suburban retrofit: Developers are buying up the tiny matchstick bungalows, knocking them down, and replacing them with 2,000-square-foot modern single-family homes in older neighborhoods. In these places, walkable locations — not houses — are what the market is chasing.

Meanwhile, in Troy, Farrell doesn’t disagree with the characterization that the city’s current strength is somewhat a matter of running on fumes more than a sign of future momentum. He worries in particular that in an era where the workforce is increasingly choosing where to live first, then looking for employment, Troy’s legacy housing and lack of walkability hurt its chances in the evolving competition between our urban and suburban places.

“It’s never been more difficult than it is today to recruit companies to come to Troy, Farmington Hills, Southfield, and markets that have been easy in the past,” he says. “Royal Oak, Plymouth, and Rochester are winning that battle. The city of Detroit is winning that battle. Some people might have a hard time hearing that, but Detroit is very real competition.”

Troy: c.1980 & Today

Photos of Troy in the 1980s (top) show a community defined by single-family households. Portraits of life today (bottom) reveal how changing demographics are reshaping the city’s identity. An aging population means two-thirds of households are childless; roughly 20 percent of residents are of Asian descent.

When Savidant finally opens the spiral-bound book that’s been until now sitting restlessly under his hands, the vision for Troy’s future town center proves to be more exciting than a Starbucks. If the cafe felt like dipping a toe in the suburban retrofit pool, this is a dive into the deep end: The set of colorful artist renderings shows a whole new walkable, citylike neighborhood that combines just about everything from an urban planner’s fetish list. Tucked along the eastern edge of the Big Beaver corridor, there are blocks of smaller-footprint, small-lot cottage-style homes; new streets that mix and match apartments and condos with ground-level storefronts, offices, restaurants, and a boutique grocery. Sixty of the town center’s 125 total acres are new parks. There are even plans to build a 5-acre lake. And unlike on the Big Beaver of today — at least in the drawings — there are people on the sidewalks.

The project, which the city has been planning for more than a year and hopes to soon attract a developer for, is often described in the media as an attempt to give Troy the downtown it never had. But Savidant resists the characterization, and he’s likely right to do so. By the numbers, the town center is mostly housing — 800 units total. What’s different for Troy is that it’s a kind of housing that lets people live, work, shop, and go to the park without getting in the car. As such, it’s a direct attempt to address what city leaders see as Troy’s core vulnerability: That they need more than just large homes on cul-de-sacs to adapt to changing times.

Bob Gibbs, the project’s designer, says his inspiration actually came from a nearby source: Birmingham, a metro Detroit community unique for its historic urbanism, and one which is far from the center of the conversation about potential trouble in the suburbs. “People say, ‘Oh, that’s because Birmingham is rich,’ ” Gibbs says. “I say it’s wealthy because it’s planned. Back in the 1920s, Birmingham hired a Harvard urban planner to build their civic plan. The planner said, ‘Buy five blocks of houses and tear them down and build a park, build a city hall, build a library.’ So they did it. Could you imagine — a city buying five blocks of occupied housing and tearing it down, just because a planner told them to? But I think they’re reaping the benefits today.”

Troy likely won’t have to do anything quite so dramatic to build its town center. The potential site is a sprawling, publicly owned civic campus that, right now, houses the city hall, library, community center, playgrounds, an aging swimming complex, half a dozen overbuilt parking lots, and plenty of open space. It’s not exactly a park; more like large swaths of well-maintained lawn surrounding the main buildings. But as a mostly open area in a sea of suburban development, it’s often described as the most valuable undeveloped site in the region.

But the idea of remaking the largest piece of public open space in Troy into an urbanlike neighborhood isn’t a vision that everyone here is comfortable with. In July, at an informational public meeting about the project, it took just two minutes to see that the city’s presenters were going to be on the defensive; another 30 minutes for Bob Gibbs to get into a mild shouting match with a longtime resident who argued this plan would turn “Troy’s Central Park” into an enclave community. Gibbs insisted the design was built to do the opposite, but it was clearly a tough sell.

After the meeting, Gibbs said he wasn’t surprised by the reaction. A few years back, he was hired to design a much smaller but similar project for Rochester Hills. His original plans called for three stories, with retail, restaurants, and offices on the bottom level with apartments and condos above. “When I proposed it, the city just rolled their eyes and said, you know, ‘No way, we don’t want renters living in Rochester Hills.’ ” The built version ended up as a one-story outdoor mall without a single house or apartment. They even insisted on an earthen wall separating it from the nearby neighborhood. “Designing these things is the easy part. Politically, they can be impossible.”

It’s difficult not to frame the emerging debate over Troy’s town center project — and its retrofit plans in general — as a clash of future and past visions of the city. When I ask to chat with members of the citizen group who felt so passionately about it they organized a petition drive to give voters a say on the project, I’m referred to Jeanne Stine and Brian Wattles. Stine, now 88, is a former mayor of Troy and moved here in 1962 when building a house here meant having a dairy farm as a neighbor. And Wattles — his family has roots which date back to 1837, and is almost apologetic that he grew up in Warren and has only lived in Troy for 31 years. (Yes, Wattles Road is named after his family.)

They have a lot of objections to the project, from what they say is a lack of public input to the simple fact that they like their civic complex the way it is. But they also just aren’t fans of bringing city living to Troy. After chatting for a bit, I joke with Stine, who recently fought the construction of a new apartment building near her neighborhood, that she uses the word “density” like it’s a bad word. “It is a bad word,” she says, only she’s not really joking.

Wattles then offers his own critique of urbanism: “My line about this walkability thing is that the only reason you see people walking in downtowns is because they had to park three blocks away to get there. Just last week, my daughter wanted to go out to eat in Royal Oak, and I had to drive around looking for a place to park. Then, the parking structure is five dollars. I tried to convince her all week that there are plenty of restaurants in Troy — and there’s plenty of parking.”

They do acknowledge the exodus of young people from the region. But they don’t buy that a more citylike Troy is going to do much to win young people’s hearts when they have other urban places to choose from. That, of course, begs the question: Who will be populating the city in the next 25 years as the population continues to age? And for that, Stine and Wattles offer their own observations of emerging demographics in America: They both say the Troy of the future will be decidedly less white.

It’s a trend that is already transforming Troy. In the past few decades, well-educated families from Asian countries, particularly China, India, and Pakistan, have been drawn in part by the engineering and technology sectors associated with the auto industry. In fact, roughly 20 percent of the city’s population today is of Asian descent, and like many residents, they have been attracted to Troy for the good school systems.

It’s a demographic that’s also leaving its own mark on the housing and redevelopment landscape. Savidant says it’s largely these immigrant groups that are feeding current demand for those four- and five-bedroom traditional homes in the city — in part to accommodate multi-generational families. And in a trend that’s almost the reverse of what’s happening in more historic, denser Detroit suburbs like Berkley and Ferndale, some residents are buying up multiple large lots with existing homes, tearing them down, and putting up even larger McMansion-style homes. It’s proof perhaps that many here are still drawn to Troy’s original postwar version of the suburban American dream.

It’s hard to say which ideal has more momentum today. Even as those larger houses are replacing mid-century ranches in subdivisions, multi-story apartment buildings and condos are popping up in other parts of Troy. But the community may soon face an important straw poll: Stine and Wattles’ petition drive will put a measure on the November ballot that, if approved by voters, could make it harder for the city to sell or lease public land — a step that’s being seen as a de facto referendum on the town center project. No one seems sure which way the vote will go. But even the specter of community ambivalence has already had an impact: Savidant says the city has decided to temporarily withdraw its request to developers to submit qualification bids for the project. That doesn’t mean the town center is dead, but where voters land — particularly if they show support for the project — could impact how quickly the city moves forward with future retrofits.

June Williamson, the City College of New York professor who inventoried hundreds of redevelopment projects for her co-authored book Retrofitting Suburbia, isn’t surprised Troy is experiencing growing pains. She says because land has always been scarce in cities, we’ve grown accustomed to understanding them as places of constant reinvention. But the postwar American suburbs, which are a development form that’s only been around for a little more than half a century, are just now entering a first phase of regeneration. As such, there’s no proven roadmap for evolution — architecturally, politically, or philosophically.

“Culturally, we understand suburbs as being built and then frozen in amber,” Williamson says. “When you run out of room in the old one, you just build a new one. So, adding the idea of retrofitting requires an adjustment in how we think about our suburban places. To some — and maybe particularly in a place like Michigan, where the car has been really important to the history and economy of the region — that’s going to feel like you’re denigrating a certain ideal. But it’s a retooling. It’s not a wholesale replacement of one thing with another. It’s about adding more diversity to the mix.”

Williamson agrees that long-term, southeast Michigan risks suffering continued population loss if it resists serving the emerging demographics looking for smaller housing and walkable neighborhoods. Oakland County alone may need to add 50,000 apartments over the next 20 years to keep pace with demand. Still, unlike some futurists who see suburbs devolving into the new American slums, Williamson is not a doomsdayer about communities like Troy. And despite acknowledgement of the urgency of the challenges, she actually advocates a certain degree of patience with the transformation process.

“My main advice would be to stay tuned to the short-, long-, and medium-term feedback loops. If people do start to move to the community in response to some of the early projects, who are they? Why are they coming? Does that match what you were expecting? And then make corrections accordingly. But the suburbs aren’t going anywhere. It’s not a zero-sum game in which cities are ascendant and the suburbs are losers. There are millions of people living there, and they can’t all be dismissed.”

Patience is something Savidant can live with. On the weekends, he’s accustomed to driving roughly 33 miles, 45 minutes depending on traffic, to Red Hook, an independently owned bakery and cafe in Ferndale so aware of its cool, it’s named after a trendy Brooklyn neighborhood. To him, the long commute is worth it — just to experience a Saturday morning on one of the more authentic, small-business focused Main Streets in the metro region. When he looks into the future, he sees a similar cafe — only he’s here, in Troy, walking down the Big Beaver corridor, having a chance sidewalk conversation with a neighbor en route to a midday latte. “When I came here in 2002, and it was lunchtime and I wanted to grab something to eat, you had to get in your car. Now, I can at least walk and grab a sandwich,” he says, laughing. “So maybe all this is just me being selfish. I mean, I would love to pay $3.80 for a coffee and $4 for a muffin like I do at Red Hook. That’s how I’ll know we’re on the right path.”

|

|

|