At the ballpark or away, Germany Schaefer was always putting on a show.

Tigers fans have enjoyed a passing parade of crowd-pleasing jokesters and flakes, including mop-haired Mark Fidrych, fun-loving Norm Cash, the irrepressible Dave Rozema, and boogying groundskeeper Herbie Redmond. For the mythic Schaefer, one has to reach much deeper into the past, back to an era when players wore pancake gloves, slept two to a bed, and traveled to games in horse-drawn coaches. Baseball was still a pastime of absurdity, melodrama, comedy, and improvisation, a far cry from the self-conscious and over-engineered industry it is today. Nobody embodied the free-minded spirit of the times better than Schaefer, a favorite of such popular raconteurs as broadcaster Ernie Harwell and newspaperman Malcolm Bingay, the Detroit Free Press’ original Iffy the Dopester.

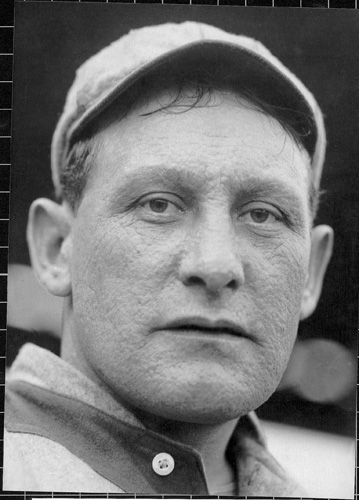

“Everybody loved the jovial, droll, pock-marked Chicago Dutchman,” said Fred Lieb, the influential New York sportswriter who also helped spread Schaefer’s legend. To Bingay, who covered the Tigers in the early 1900s, Schaefer was “the soul of baseball itself, with all its sorrows and joys, the born troubadour of the game.” He was a natural showman. He had a quick wit, a strong baritone voice, and was a master of mimicry. However, Schaefer also was “a strange, moody guy,” Bingay admitted, “a comedian with the soul of a tragedian.”

It’s tough to envision Schaefer’s brand of theatrical antics happening today, in this, the 100th anniversary year of Tiger Stadium (Navin Field).

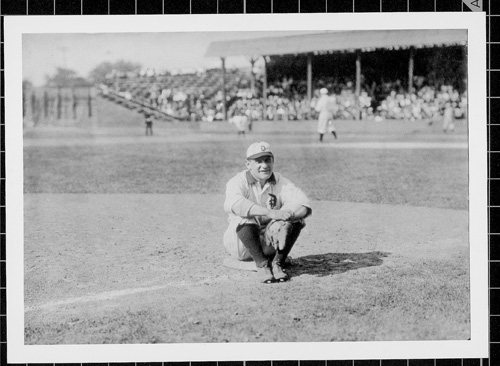

Protesting an umpire’s decision to keep a game going in fading light, for example, Schaefer trotted out to his position carrying a lantern. On rainy days, he carried an umbrella onto the field, wore a raincoat and boots to the plate, or splashed barefoot in the puddles. He tip-toed along the foul line like a tightrope walker and rowed across the outfield grass using bats as oars. And, most famously, he occasionally stole first base — a maneuver that exploited a loophole in the rules.

Schaefer first pulled off his signature stunt in a game against Cleveland, most likely in 1908 (the exact date is unclear). “They say it can’t be done,” Tigers outfielder Davy Jones told author Larry Ritter many years later, “but I saw him do it.”

Jones was on third base in the late stages of a tied ballgame. Schaefer was on first base. Hoping to draw a throw that would allow Jones to race home with the go-ahead run, Schaefer stole second. However, the catcher, wise to the strategy, held onto the ball.

“So now we had men on second and third,” Jones recalled. “Well, on the next pitch Schaefer yelled, ‘Let’s try it again!’ And with a blood-curdling shout he took off like a wild Indian back to first base, and dove in headfirst in a cloud of dust. He figured the catcher might throw to first — since he evidently wouldn’t throw to second — and then I would come home same as before. But nothing happened. Nothing at all. Everybody just stood there and watched Schaefer, with their mouths open, not knowing what the devil was going on.”

Even if the catcher had thrown to first, Jones said, he was too flabbergasted to move. “The umpires were just as confused as everybody else. However, it turned out that at that time there wasn’t any rule against a guy going from second back to first, if that’s the way he wanted to play baseball, so they had to let it stand. So there we were, back where we started, with Schaefer on first and me on third. And on the next pitch, darned if he didn’t let out another war whoop and take off again for second base. By this time the Cleveland catcher evidently had enough, because he finally threw to second to get Schaefer, and when he did I took off for home and both of us were safe.”

A man who steals bases in the opposite direction should be accustomed to reverses, and Schaefer certainly suffered his share during a truncated lifetime. He was born Feb. 4, 1876, to immigrant German parents on Chicago’s South Side. Growing up in the poor and vice-ridden Levee District, he fell victim to one of the deadly smallpox epidemics that regularly swept through the tenements. As a result of the disease’s progression of blisters and scabbing, survivors are marked for life, some more severely than others. Schaefer’s pleasant face, habitually split by a wide smile, was left badly pitted.

Schaefer was understandably sensitive about his looks, but dermal fillers, chemical peels, microdermabrasion, and other cosmetic procedures were unknown then. Shortstop Charley O’Leary, Schaefer’s lifelong pal and double-play partner, remembered a streetcar conductor calling the disfigured youngster a “sauerkraut-faced boob,” one of the gentler insults regularly tossed his way. To survive in the hard-boiled world of sandlots and saloons where Schaefer came of age, one had to respond forcefully to taunts — sometimes with an exaggerated insouciance, sometimes with a biting wit, sometimes with fists. Schaefer, who as an adult was a solid 5-foot-9 with muscular legs and a broad set of shoulders, took on all tormenters. A correspondent in Sioux City, Iowa, where Schaefer played semipro ball in 1898, later recalled the young player’s “habit of climbing into the grandstand to whip a rooter because of remarks about his pock-marked face …. Sometimes it took the combined efforts of his teammates and a couple of policemen to pry him loose from the rooter.”

Schaefer was a right-handed batter and thrower. He was quick, agile, and versatile, and eventually played every position except catcher. After stints with Kansas City and St. Paul in the Western League, he signed with his hometown Chicago Cubs in 1901. As a Cub, he became a footnote to a historic event. On Sept. 13, 1902, he was the third baseman as the fabled double-play combination of “Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance” (shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers, and first baseman Frank Chance) was configured for the first time. The trio, immortalized in verse by Franklin P. Adams, ultimately made it into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Meanwhile, the odd man out in the Cubs infield moved about for a couple of summers. Schaefer was playing for a minor-league team in Milwaukee when he attracted the eye of Frank Navin, business manager (and future owner) of the Detroit Tigers.

Navin wasn’t sure he really wanted to sign the mercurial shortstop, who during his baseball travels had already acquired a reputation as a “jakey,” slang for a hard-core alcoholic. “I have heard so many conflicting stories about Schaefer that I am somewhat dubious regarding him,” he admitted. Nonetheless, in November 1904, Navin sent popular infielder Clyde “Rabbit” Robinson and $2,500 to Milwaukee for Schaefer. The newcomer’s feistiness accounted for the Tigers’ unexpected third-place finish in 1905, claimed Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. “With old Schaefer in there, fighting all the while, there has been a marked difference in their playing.”

It was against the White Sox that Schaefer pulled off one of his most memorable stunts. On June 24, 1906, the visiting Tigers were losing, 2-1, and down to their last out. Charley O’Leary was on first base when Schaefer was sent up to the plate to pinch-hit against “Doc” White, one of the toughest pitchers in the game. Just as he was about to step into the batter’s box, Schaefer turned around, took off his cap, and addressed the large Sunday crowd. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he announced, “you are now looking at Herman Schaefer, better known as Herman the Great, acknowledged by one and all to be the greatest pinch hitter in the world. I am now going to hit the ball into the left-field bleachers. Thank you.”

Lost in the folklore surrounding this incident is that Schaefer, who claimed to be “psychic,” often entertained the crowd by telling them what was going to happen on the field. Fans either hooted or cheered; it was part of the give-and-take between the babblative ballplayer and the public. Nobody kept track of the number of empty boasts or failed predictions. This time, though, Schaefer delivered, sending White’s second pitch into the bleachers, as advertised.

Schaefer, a .258 career hitter with a paltry total of nine home runs in 15 big-league seasons, may have been the most surprised person in the park. He jumped with glee as the ball cleared the fence. Seizing the moment, he bolted like a racehorse toward first base — then dived headfirst into the bag. He got up and shouted, “At the quarter, Schaefer leads by a head!” He slid into second, yelling, “At the half, Schaefer leads by a length!” He then slid into third, announcing, “Schaefer leads by a mile!” He concluded his gallop around the bases with a fancy hook slide into home plate and a cry of “Schaefer wins by a nose!” He dusted himself off, doffed his cap, and bowed. “Ladies and gentlemen, this concludes this afternoon’s performance. I thank you for your kind attention.” The Tigers won, 3-2, and another chapter in the legend of Germany Schaefer, the “clown prince of baseball,” had been written.

Schaefer seemingly was pals with everybody he met. He took the field against black players in offseason exhibitions in such places as Harlem and Cuba, happily exploring the local culture in post-game revelries, and back-slapped stern-looking dignitaries as if they were old friends. A few years ago, an album of century-old snapshots by Tigers outfielder Matty McIntyre came up for auction on eBay, creating a minor stir among collectors. It was a rare and remarkable peek into the everyday world of baseball, circa 1905. Unsurprisingly, Schaefer is the center of attention in many of the candid “Kodaks.” He is seen approaching a washwoman on the sidewalk of an unidentified Southern city, talking animatedly with a bearded Jewish peddler in downtown Detroit, and mugging with a black family in Georgia. The knee-jerk impression is that Schaefer was having fun at their expense while McIntyre snapped away with his $1 Brownie camera, but contemporary accounts of Schaefer’s shenanigans insisted his humor was never cruel, belittling, or patronizing. “With all his ‘kidding’ and fun-making Schaefer is never offensive,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer observed in 1908.

The silver-tongued Schaefer was relentless. Cobb, who came up to Detroit as an 18-year-old rookie in 1905, recalled how Schaefer would position himself on the back step of the tally-ho taking the team to Bennett Park and hold running conversations with strangers. “My, what a pretty infant!” he’d call out to some lady pushing a carriage on the sidewalk. “What’s his name?”

“Augustus!” the startled mother would shout. “And how old is the little darling?” Schaefer would bellow as the clopping horses continued to put distance between them.

“Ten months!”

“Is he an only child…?”

“By now,” Cobb marveled, “all street traffic would have stopped to listen open-mouthed to the dialogue and Germany never considered the stunt a complete success unless he still had the mother screeching answers when we were half a block away.”

The high-strung “Georgia Peach” had few friends on the team, but Schaefer, who admired Cobb’s competitiveness and craftiness, was one of them. The two were key cogs in Detroit’s 1907-08-09 pennant winners, though Schaefer would be traded late in the 1909 season. “As a drawing card, Herman ranks second only to Cobb,” Harry Salsinger wrote in The Detroit News. “Schaefer gives the comedy, Cobb the thrills.” It was a measure of Schaefer’s savvy that, on a roster studded with future managers and Hall of Famers, manager Hughie Jennings named him the Tigers’ field captain. This responsibility came with an extra $500, a significant amount of money at a time when most players made $2,000 or $3,000 a year.

Money was on Schaefer’s mind when, acting as the players’ representative, he asked what seemed to be an inconsequential question at a meeting with baseball officials before the start of the 1907 World Series. “Under the rules, the players share in the gate receipts of the first four games,” he said. “If there is a tie game among the first four, do we share in the gate receipts of the fifth game? We think we should because it would be a game that would have to be played over again.” The issue had never come up before. There had never been a tie game in World Series play. Officials huddled and, deciding that the odds of such an occurrence were slim, agreed to the new provision. The next afternoon, Detroit and Chicago played to a 3-3 tie that was called after 12 innings because of darkness. Schaefer later said the question had come to him in a vision.

The 1908 campaign was Schaefer’s all-around finest, though, once again, the Tigers lost the World Series to the Cubs. He finished third in the league in runs, stolen bases, and sacrifice hits, as the Tigers squeaked by three other teams in the final week to win a second straight pennant. That June, during an evening of drinking in the bar of the Brunswick Hotel, a loudmouth disparaging the Tigers took a swat at Schaefer. Schaefer “lost his usually calm temper” and administered “a thorough beating,” reported the Free Press. After sobering up, the victim wrote him a letter, apologizing for his loutish behavior and saying how much he admired the combative team leader.

Aside from drinking, Schaefer’s major vice was gambling. Once, during a convivial gathering at a friend’s place, he asked the lady of the house if there were any playing cards around. “No, Mr. Schaefer,” she said, “we don’t have card-playing here.”

“Well, have you got some dice?”

“I tell you,” the woman said, “we don’t allow gambling of any sort.”

“Well,” he said in exasperation, “have you got any washtubs in the cellar?” Told that there were a half-dozen tubs there, he said, “Well, for the love of mud, get me three tubs and I’ll work the three-shell game!”

In August 1909, Schaefer was sent to Washington as the Tigers revamped their infield. In the waning days of the pennant race, American League president B. Bancroft “Ban” Johnson ordered him to sit out Washington’s final series against Detroit. Johnson was worried that Schaefer, who had been told by the Tigers that he would receive a World Series share, might be tempted to go less than full-bore against his ex-teammates. The Tigers clawed their way to a third straight pennant. Just before the Series opener against Pittsburgh, Schaefer was spotted trying to get a bet down on his old team. A few minutes later, he entered Bennett Park to cheers from the grandstand. He watched the Tigers lose a third straight Series from the Detroit bench.

Schaefer stayed with the Senators for the next five seasons. In a 1911 game against the White Sox, he again stole first base, with the umpire insisting afterward that Schaefer had “a perfect right to go from second back to first.” According to a 1912 issue of Sporting Life, “Schaefer is such a hit with the crowds that the umpires are giving him every liberty to do as he pleases.” He spent more time in the coaching box, where in addition to his comedy routines he was a first-class sign-stealer.

Schaefer occasionally worked the vaudeville circuit, appearing at Detroit’s Temple Theater with Broadway actress Grace Belmont just before Christmas in 1911. During that tour, the vaudevillian-ballplayer was sharing a compartment on an overnight train when he drew the ire of his fellow passenger for keeping a lamp on while reading. After a prolonged exchange of unkind words, Schaefer turned off the light and patiently plotted his next move in the dark. It wasn’t until the following morning, when his antagonist got up, dressed, and left the train, that Schaefer realized he had thrown his own shoes out the window.

Schaefer never married. He preferred tossing dice, telling stories, and drinking with his buddies to settling down. Like many bachelors, his “best girl” was his mother, to whose Chicago flat he often returned in the offseason. Sophie Schaefer’s death had a bit of dark slapstick to it, the 73-year-old widow tumbling out of a second-story window one Sunday morning in 1913. That year, Schaefer was a member of an all-star team that toured the world. He was a natural ambassador. In Tokyo, he glibly addressed a crowd of 10,000 Japanese for a half-hour. “They had no more idea what he was saying than he did,” Malcolm Bingay wrote. “But they cheered him wildly.”

Now approaching 40, Schaefer was slowing down as a player. After Washington let him go, he joined Newark, a team in the short-lived Federal League, for the 1915 season. He then worked as a coach for the Yankees, managed by ex-Tiger teammate “Wild Bill” Donovan. With World War I raging and patriotism on the upswing, Schaefer announced he was changing his nickname from Germany to “Liberty” Schaefer. Fans still appreciated his schtick, but sometimes he was feeling too poorly to perform his usual tricks.

Schaefer joined the Cleveland Indians as a coach in 1918. During the Tigers’ home opener against Cleveland, his voice — once described as being able to penetrate 6 inches of chilled steel — could scarcely be heard by his old friends in the press box. The fall-off in volume and vitality was attributed to a cold. In reality, he was dying of what was known as “consumption” (pulmonary tuberculosis). “Even in his later years, when failing health and straitened finances took much of the joy out of life, Schaefer could still see the funny side,” Fred Lieb wrote. “Patronage fell off, and to cut expenses Coach Schaefer was let out. ‘Now, see what you birds have done,’ he said half in anger and half in jest. ‘You’ve run your losing streak so far you’ve run me right out of a job.’”

New York Giants manager John McGraw put the sickly prankster on the payroll as a scout. On the morning of May 16, 1919, Schaefer was aboard a train in upstate New York when he suffered a brain hemorrhage. He was rushed to a hospital at Saranac Lake, but within an hour, he was dead at 43. Some said there was a trace of a smile on his face. “Because he was a ‘kidder’ and a baseball comedian, Schaefer never got full credit for his baseball brains,” eulogized the Free Press. “He was a good fielder and a fair hitter, but his real strength was in his baseball brain and in his gameness.” A few months later, baseball’s rules committee issued an overdue clarification: “A base-runner having acquired legal title to a base cannot run bases in reverse order for the purpose of confusing the fielders or making a travesty of the game.” The clause was officially known as Rule 52, Section 2, but most people in baseball referred to it as the Germany Schaefer rule.

Schaefer rests at St. Boniface, a small German Catholic graveyard on Chicago’s north side. He’s among 14 family members crowded under a weathered 19th-century monument. The simple inscription, “Herman W. Schaefer,” is nearly indecipherable. The stone is badly pitted.

Chummy and unadorned suits the man. Once, asked what he intended to do after he retired from baseball, Schaefer said that he’d like to buy a little corner saloon. “Not a big gaudy place,” he said, “but a cozy spot where my friends can enjoy a glass of beer and a sociable evening. And along about 10 o’clock every evening I want one of my pals to say to the bartender on duty, ‘Where’s old Schaef tonight?’ And I want my bartender to be able to say, ‘He’s upstairs, drunk.’

If you enjoy the monthly content in Hour Detroit, “Like” us on Facebook and/or follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates.

|

|

|