In the Roaring ’20s, the 18,000-square-foot house on Detroit’s Boston Boulevard itself roared with activity. The clamor of children’s voices, the bustle of 17 live-in servants, and the lively conversation of guests in the ballroom animated the home.

There were also informal gatherings in the downstairs pub, the air choked with cigar smoke, while men talked robustly of business and finance amid the clack of billiard balls in an adjoining room. Sometimes the majestic Estey pipe organ in the foyer permeated the sprawling mansion with its stentorian notes.

Fifty years later, those sounds surrendered to silence. The lady of the house, then in her 90s, lived there quietly, her circle of servants narrowed considerably, the children grown, her husband dead since 1963. She maintained the home until her death in 1974.

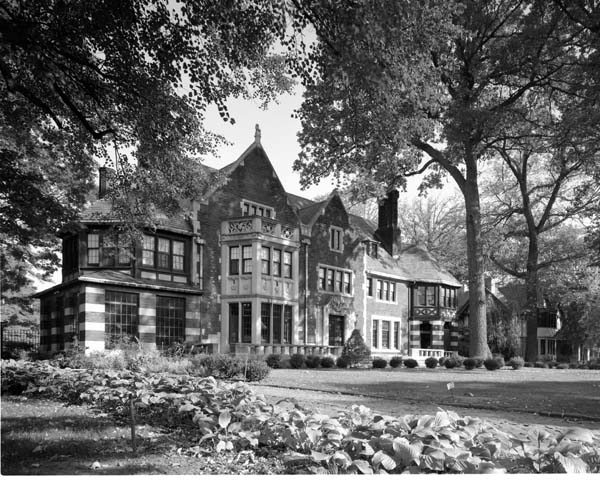

Today, a different kind of noise is enlivening the home, which was built in 1922 for Charles and Sarah Fisher, of the “Body by Fisher” family. The rat-a-tat of hammers and the clang of plumbers’ wrenches punctuate the renovation taking place. Outside, landscapers are busy planting trees and bushes, while three stories up workers repair leaks to the slate roof.

Michael Fisher, a cousin to the Charles Fisher family, bought the house three years ago. He’s an old hand at renovating stately homes, having first purchased a house in 1993 on Seminole in Indian Village. Then, in 1997, he bought and refurbished the Italianate manor built for Benjamin Siegel (the founder of B. Siegel, the tony women’s shops) just east of the Fisher home. Even before he owned his present residence, Fisher says he was attracted to it. “I once was invited to a Halloween party here, and I walked in the front door. My cousin was with me, and I told him, ‘I’m going to own this house someday.’ ”

A DAUNTING PROJECT

That “someday” wasn’t just an elusive dream. But owning a house, no matter how fond one is of it, requires constant care. And with 48 rooms, the Fisher mansion demands more attention than a classroom of fidgety preschoolers. That’s why Fisher, director and owner of the Fisher Funeral Home in Redford Township, hired Drew Esslinger, an estate manager who runs the household with swift efficiency. The plan is to restore the manor as much as possible to the way it originally looked. That effort is aided in part by photographs of rooms taken in 1922 and blueprints from architect George D. Mason, who, four years later, would design Detroit’s Masonic Temple.

In just three years, progress has been steady.

“The front of the house was completely covered by pine trees and yews; you could barely see the house,” says Esslinger, who also lives in the house. “The entire front porch was caved in, so that was completely restored. Now we’re doing repairs to the roof and major plumbing work,” he says.

As evidence of the headway he’s making, Esslinger shows his visitor a recently renovated blower for the pipe organ.

It’s Esslinger’s task to track down expert craftspeople, and he doesn’t take rejection lightly.

“When people say, ‘Oh, we can’t renovate it; it has to be gutted,’ I say, ‘I’m sorry, but I know it can be done, and I’ll get someone else to do it if I have to search the country.’ ”

Fisher estimates that it will take another five years before the home is completely restored, but, having already refurbished two old homes, he’s learned not to set precise timelines.

“When you have a house of this age and size, you may have your own plan, but the house ends up telling you what you’re going to do,” Fisher says. “You could say, ‘This year, I’m going to buy new rugs, paint this room, and do this or that,’ but maybe the boiler gives out. The house has its own agenda.”

To prove his point, Fisher mentions a bathroom (there are 17 in the house) on the third floor where a pipe sprang a leak. “We had to gut the walls out of the shower and replace it, and now we’re re-tiling it. It kind of throws my schedule off.”

Some might say that renovating a home of that scale is too expensive, too demanding, but Fisher sees it differently.

“Detroit cannot afford to lose one more piece of its history; it can’t afford to lose one more significant building. We’ve already lost too much.”

Though born in Detroit, Fisher grew up primarily in Fowlerville, but family stories about Detroit’s glory days intrigued him. “I heard how fantastic Hudson’s was, how great the streetcars were, and how crowded it was downtown,” he says in the sunroom on a mild October evening. “I always felt there was a part of me, long before my time, that was part of Detroit. I could just feel my essence was here.”

A REMARKABLE HOME

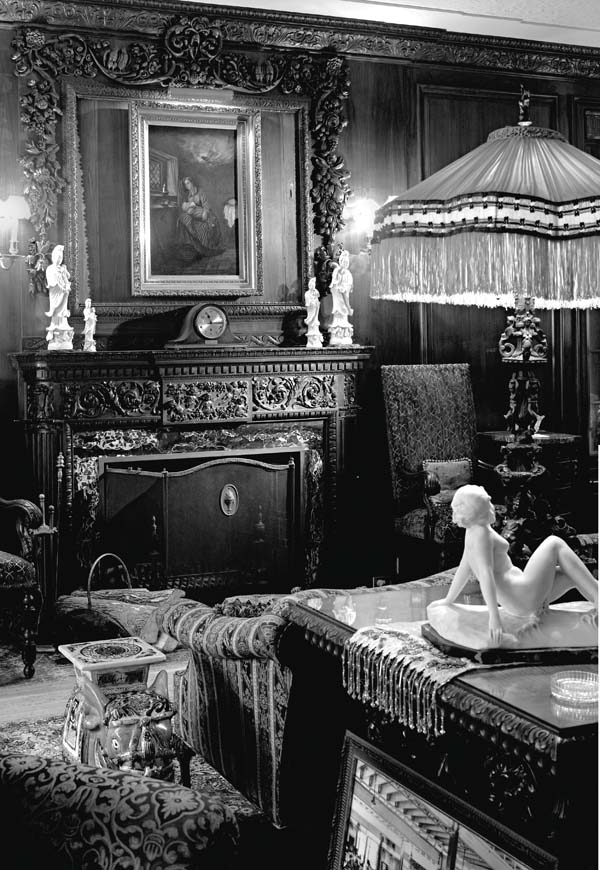

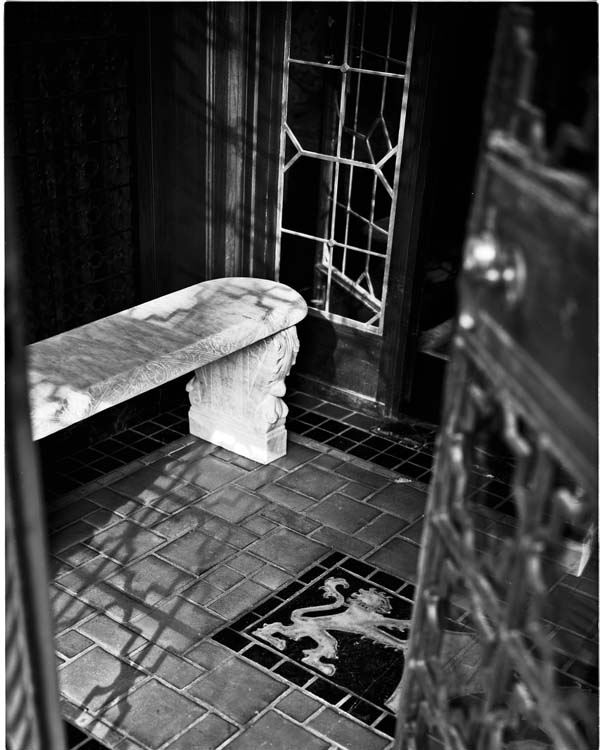

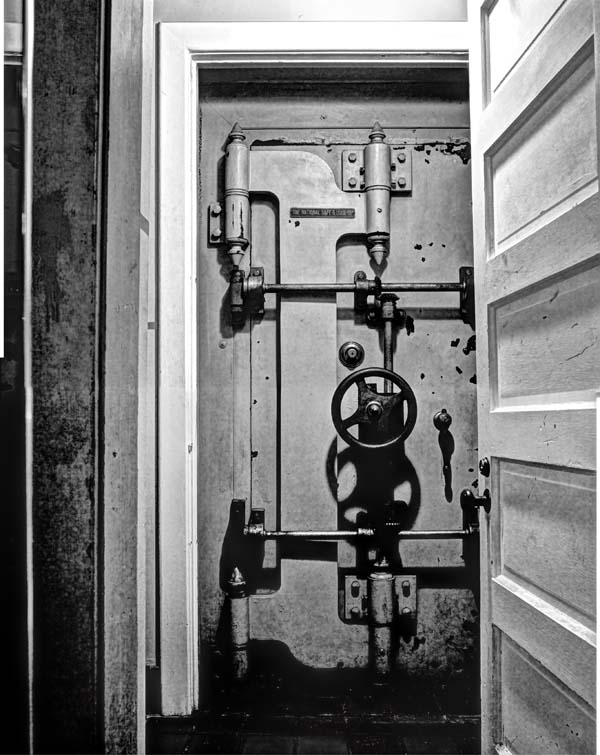

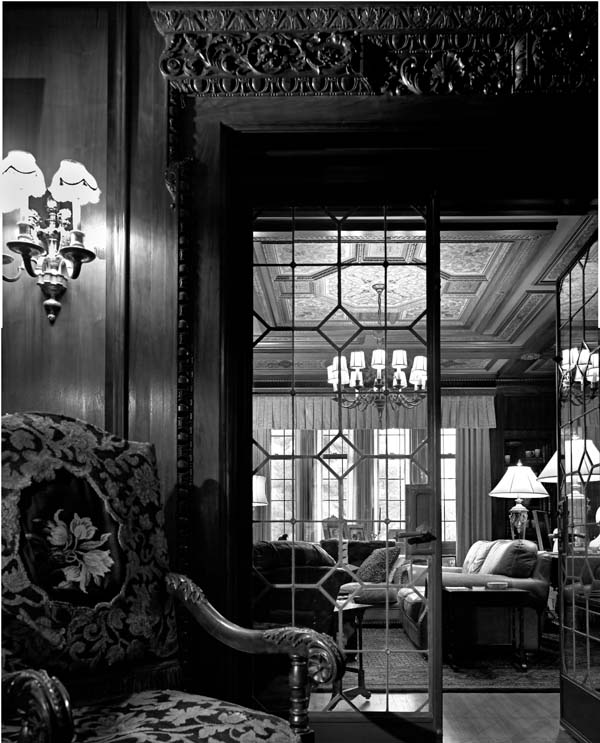

Walking through the 12-bedroom (there are two more in the carriage house) Fisher dwelling, the largest home in the historic Boston-Edison district, leaves no doubt that it is, as Fisher says, “a significant building.” Among its many notable details: custom-made Pewabic tile floors in the sunroom and hallway; an English walnut staircase with finely carved lions and falcons; an elaborate marble fountain in the sunroom, a trompe l’oeil tapestry ceiling in the library that’s actually hand-stenciled wood; leaded-glass Art Deco-style doors on the first floor; two walk-in vaults and six safes (one used to store booze during Prohibition); an Art Deco-style pub in the basement; a marble-floored ballroom; and a chapel.

“The house was modeled after English countryside Tudors in the 16th through 18th centuries,” Esslinger says. “But there’s a lot of Art Deco and some Art Nouveau in the house, too. That was very typical architecturally of that time period.”

Fisher, the home’s fifth owner, has furnished it with family heirlooms, as well as antiques and furniture he finds at auctions, estate sales, and through the help of a dealer friend. Some pieces came from the Siegel home, including furniture, a painting by Detroit artist Myron Barlow, and a regal walnut grandfather clock on the landing that was a wedding gift to Benjamin and Sophie Siegel in the early 1900s.

Other acquisitions include a white-marble bust of Delphine Dodge that had originally been in Grosse Pointe’s Rose Terrace (the home of Horace and Anna Thomson Dodge), and an Art Deco light fixture in the sunroom that once hung in New York’s Chrysler Building.

In the 56 years that the Fishers lived there, relatively few renovations were made. The most significant was a kitchen remodeling by J.L. Hudson in 1947. The library was originally a billiards room, but Fisher says Sarah couldn’t abide the cigar smoke while Charles and his colleagues kicked back. “So she moved the billiards room to the basement, which had been a sitting room next to the ballroom. In the library, she installed a fireplace, which was imported from Europe.”

THE FISHER DYNASTY

When Charles and Sarah Fisher built their imposing residence, Detroit was a booming place, the fourth-largest city in America. The auto industry enabled some to make fortunes tantamount to King Solomon’s mines. The cliché about Detroit’s being a blue-collar town is only partly right. What’s not often mentioned is the tremendous wealth that created such neighborhoods as Boston-Edison, Indian Village, and Palmer Woods. When it was built, Boston-Edison, then considered the north end of town, was an enclave of the new rich, including titans of business and industry. (See below for more neighborhood history). Henry Ford lived here, as did Fred Sanders of the confectionery company; Sebastian Kresge, of five-and-dime fame; Ernst Kern, of Kern’s department store; Moses Himelhoch, founder of the upscale Himelhoch’s stores; the Wagner family (owners of Wonder Bread); Ira Grinnell, who started Grinnell Brothers Music; Walter Briggs, owner of Briggs Stadium (later Tiger Stadium); politician and Ford Motor Co. executive James Couzens; and a screed of others.

“This was Millionaires’ Row,” Esslinger says. “They were the Bill Gateses of their day. Everything was top of the line.”

The neighborhood had a rarefied air, precisely the kind of place where Charles and Sarah Fisher wanted to bring up their three sons and two daughters.

Charles’ parents, Lawrence and Margaret Fisher, of Norwalk, Ohio, had 11 children, seven of them sons — Fred, Charles, William, Lawrence, Edward, Alfred, and Howard. The senior Lawrence owned a horse-carriage company. As young men, Charles and Fred moved to Detroit, and with bankrolling from an uncle, they founded the Fisher Body Co. in 1908. But their carriages were made for the nascent auto industry, not for horses. Although the company later designed bodies strictly for General Motors, in the early years clients included Ford, Studebaker, Chalmers, Hudson, Packard, and other corporations. The Fisher factory stood at Piquette and St. Antoine.

Eventually, the younger brothers joined Fisher Body, which was a cash cow. The brothers grew to be almost incalculably rich. In 1919, they sold 60 percent of the company to General Motors, and, in 1926, GM purchased the remainder. But Michael Fisher says the brothers weren’t content to be counted among the idle rich. “They were still significant shareholders. Most of the brothers held positions with GM, and they had an investment firm, too.”

Fisher is quick to point out that a segment of his family who had made their fortune in lumber, and whom he calls the “old Fishers,” was already in Detroit and suggested the Ohio Fishers come up to work in the burgeoning auto industry.

THE FISHER LEGACY

The “new” Fishers made an indelible mark on Detroit, and not just with their company. In 1927, the seven brothers commissioned Albert Kahn to design what would be promoted as “the world’s most beautiful building,” the Fisher Building. No expense was spared. Gold leaf adorned the ornate arcade ceiling. Forty types of marble from around the world were used inside and out. More than 400 tons of bronze ornamented the grand edifice on West Grand Boulevard. The structure’s golden tower became one of the city’s most identifiable features. The brothers kept offices in the Fisher Building, which originally was to be much larger, but the Great Depression put the kibosh on that.

The Fishers were famous for their philanthropy. They gave boatloads of money to Catholic charities, schools, and churches, and donated works of art to the Detroit Institute of Arts. The Bertha (Fred’s wife, also known as “Dollie”) Fisher Home for Aged Poor on the city’s northwest side is no longer in operation, but the St. Vincent and Sarah Fisher Center, which provides educational assistance, is still open. There are also wings named after the Fishers at Providence and Harper hospitals.

The seven brothers also constructed a nearly 40,000-square-foot house in 1925 for Bishop Gallagher on Wellesley Drive in Palmer Woods, a home later owned by Piston John Salley.

Although Charles and Fred started Fisher Body, Michael Fisher says they welcomed their younger brothers to the firm with an egalitarian spirit.

“They gave them equal shares,” he says. “They didn’t say, ‘You’re the little brother, we started the company, so you don’t get as much.’ It just shows you the love they had for each other and their strong sense of family.”

Affluent as they were, the Fishers didn’t flaunt it, Fisher adds.

“On any given day, you could go down to the New Center area and run into one of the Fisher brothers, but you didn’t know them from the next guy. They certainly could afford chauffeurs, but they drove themselves to work. They didn’t lead the splashy lifestyles of some of the other auto barons of the day.”

Except for Lawrence, the fourth-born brother. There weren’t exactly “seven brides for seven brothers,” because Lawrence got hitched late in life, and the union was brief. His siblings may have been reserved, but Lawrence, who also headed Cadillac Motors, was a different breed. He hired C. Howard Crane, better known as an architect of ornate theaters — including Detroit’s Fox Theatre — to build his luxurious Mediterranean-style home on Lenox, overlooking the riverfront.

“He was the flamboyant, loud one,” Esslinger says. “He had Hollywood stars there all the time, like Greta Garbo and Jean Harlow. He had every kind of Cadillac you could think of, and he would paint the Cadillacs to match his suit for the week. He also owned peacocks and tortoises. He was quite a wild guy.” Lawrence’s east-side mansion is now the Bhaktivedanta Cultural Center belonging to the Hare Krishna group.

Although Charles and Sarah kept a relatively low profile, they still enjoyed the good life. In addition to their Detroit manor, they owned a winter home, “Five Across,” in Golden Beach, Fla.; Dixiana Farm, outside Lexington, Ky., where Thoroughbreds were raised; a summer home on Grosse Ile; and several yachts, including the 153-foot Saramar III. They also traveled extensively, particularly to Europe. They were good friends with their next-door neighbors, the Briggses, and two of the Fisher boys married two of the Briggs girls.

SARAH’S SPIRIT

All six of Charles and Sarah’s children are dead. The last to survive, Mary, who died in 2007, lived on the family’s Kentucky farm but made trips to Detroit to care for her mother in the 1970s. With her resources, Sarah could have moved anywhere, but she chose to remain on Boston Boulevard. It was she, not her husband, who picked George Mason as the home’s architect, and she worked closely with him. “All the Fisher women chose the architects,” Esslinger says. “The husbands didn’t have much say. Sarah really loved this house; this is what she created.”

Toward the end of her life, Sarah attended Mass in her home when she could no longer make it to the nearby Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament, Esslinger says. “A priest would come, and the archdiocese would send someone to play the organ.”

Sarah died of natural causes in her bedroom, but those who live and work in the Fisher estate say they’ve felt Sarah’s presence.

The household chef, Jackie Anderer, says she feels Sarah in a corner of the basement pub. Esslinger has sensed her spirit on the stairway. “As I walk up the stairs, sometimes I feel someone brush past me,” he says. And Fisher has his own eerie stories.

“From the very first day I moved here, I could feel something, and see a shadow, as I looked down the stairs that lead to the basement. Every time I walked past the stairs, I felt someone was down there, but not in a scary way. I even put a lamp on a timer that stays on all night. I’ve also felt a very strong presence in my bedroom.”

The specter has been noted by still others. “I had a friend who did all of my Christmas decorating,” Fisher says. “He was a night owl, and he said he saw something on the stairs in the middle of the night.”

If that spirit is Sarah’s, no one in the home is frightened of her, least of all the owner. It’s as though she is benevolently watching over the restoration of her former home.

“Anything I’ve ever felt was calm, peaceful, and friendly,” Fisher says. “Whoever or whatever is here likes it and appears to be happy with what we’re doing to the house.”

BOULEVARD OF DREAMS

In the early years of the 20th century, some of Detroit’s grandest homes were built in the Boston-Edison district. These select six, all on Boston Boulevard, were designed for titans of business and industry, but cultural and entertainment giants also inhabited the gracious manors.

1. S.S. KRESGE HOME

Built for Sebastian Spering Kresge, founder of the five-and-dime empire S.S. Kresge Corp. (later Kmart), this Mediterranean villa-style mansion with white-stucco exterior was built in 1914 by the Cleveland architectural firm Meade and Hamilton.

2. BENJAMIN SIEGEL HOME

This Italianate villa built entirely of limestone and immediately west of the Kresge residence was designed by Detroiter Albert Kahn in 1915 for Benjamin Siegel, owner of the B. Siegel upscale women’s clothing stores.

3. BERRY GORDY JR. HOME

Built in 1917 for Nels Michelson, who made his fortune in lumber and real estate, this Italian Renaissance Revival mansion in limestone was bought by Motown Records founder Berry Gordy Jr. in 1967. Although he moved his company to the West Coast in the early ’70s, Gordy owned the home until 2001.

4. WALTER O. BRIGGS HOME

Erected in 1915 by the Detroit-based architectural firm Chittenden and Kotting, the English manor-style house in fieldstone was built for Walter O. Briggs, founder of Briggs Manufacturing and later owner of the Detroit Tigers and Briggs Stadium. It’s immediately west of the Fisher mansion.

5. OSSIP GABRILOWITSCH HOME

This 1912 home with French and Mediterranean influences was built for Charles Lambert, president of the Regal Motor Car Co. However, from 1918 until his death in 1936, it was inhabited by concert pianist and Detroit Symphony Orchestra music director Ossip Gabrilowitsch and his wife, Clara Clemens, daughter of Mark Twain and a renowned concert contralto.

6. IRA GRINNELL HOME

Immediately east of the Fisher estate is this Tudor/American eclectic house erected in 1911 for John W. Drake, president of the Hupp Motor Car Co. But its most famous resident was Ira Grinnell, of Grinnell Electric Auto Co. and Grinnell Brothers music fame. E.R. Dunlap was the architect.

A Slice of History

Boston-Edison encompasses about 900 homes of wide architectural variety and is bounded by Boston Boulevard on the north, Edison on the south, Woodward on the east, and Linwood on the west. Most residences on the four streets — Boston Boulevard, Chicago Boulevard, Edison, and Longfellow — were built between 1905 and 1925.

From the outset, the district was fashioned to appeal to the wealthy. “All the homes are custom-designed,” says Jerald A. Mitchell, archivist and historian for the Historic Boston-Edison Association. “There were specifications in terms of home size, materials, setbacks, and lot size.”

Mitchell, who has lived in Boston-Edison since 1972, owns a house on Edison that was built for Henry and Clara Ford in 1908 — the same year the Model T was introduced.

Although the Fords moved in 1915, Mitchell, a retired Wayne State University anatomy professor, says Henry Ford’s stay on Edison was “the most important period of his life. He did everything then that would help shape the trajectory of the 20th century.”

In the early 20th century, neighborhood restrictions regarding race and religion were common. But Boston-Edison was more tolerant, Mitchell says.

“There weren’t any of the odious religious covenants that were typical of that time, and as a result, it was open to Jews, who became very prominent members of our neighborhood.” They included Rabbi Leo M. Franklin, who served Temple Beth El from 1899 to 1941.

“We were probably the first upscale neighborhood to become integrated,” Mitchell adds. “African-Americans began moving to Boston-Edison in the late ’40s and early ’50s.” Among the first was pharmacist Sidney Barthwell, who owned Barthwell Drugs.

More information: historicbostonedison.org.

Mason’s Mark

Although born in Syracuse, N.Y., George DeWitt Mason’s signature is scrawled all over Detroit. He moved here with his family in 1870. In 1878, he partnered with Zachariah Rice to form the architectural firm Mason and Rice. That relationship lasted 20 years, after which Mason struck out on his own.

In addition to the 1922 Charles Fisher mansion on Boston Boulevard and several Grosse Pointe manors, Mason (1856-1948) also designed a bevy of local land-

marks, some of which have been razed. They include:

• The old Detroit Opera House on Campus Martius. The first building, erected in 1869, was destroyed by fire, but was rebuilt by Mason in 1898. Later the site of Sam’s Cut-Rate store, it was demolished in 1966. It is not associated with the current Detroit Opera House on Broadway.

• The original Pontchartrain Hotel, which stood at the site of what is now the City National Building. Built in 1907; razed in 1920.

• The Century Club (1903) and Gem Theatre (1927). The building was moved from Columbia Street to Madison in 1997 to make way for Comerica Park.

• The Mediterranean-style Detroit Yacht Club (1923) on Belle Isle.

• Detroit’s Masonic Temple (1926), at 500 Temple. Mason’s chef-d’ouevre, the limestone Gothic building is the world’s largest Masonic Temple, containing more than 1,000 rooms, including an ornate auditorium seating close to 5,000, the Scottish Rite Cathedral, the Fountain Ballroom, the exquisite Crystal Ballroom, and a spacious Drill Hall (with a floating floor).

• The Shingle-style Belle Isle Police Station (1893).

• Mason also designed several houses of worship in the city, including Central Woodward Christian Church (1928), Trinity Episcopal Church (1892), and First Presbyterian Church (1889).

Mason is credited with giving a young German-born Detroiter his first job. His name was Albert Kahn. Mason collaborated with his protégé on the Belle Isle Aquarium (1904) and the Palms Apartments on East Jefferson (1903).

A long way from Detroit, the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island also bears Mason’s talented touch.

THE 37TH ANNUAL BOSTON-EDISON HOLIDAY HOME TOUR (which does not include the Charles Fisher mansion) takes place Dec. 11. Tours of five homes festooned in seasonal decorations begin at the Sacred Heart Academy, Linwood at Chicago Boulevard. Buses leave every 20 minutes from 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Tours last approximately two hours. Following the combination walking-bus tour, refreshments will be served at the Sacred Heart Academy. Tickets are $20 ($10 of which is tax deductible) and must be purchased in advance; 313-883-4360; historicbostonedison.org/tour.shtml. There is also a VIP Preview Tour on Dec. 10, 6-10 p.m., which includes a motor-coach ride to participating homes and complimentary edibles at another home in the neighborhood. Tickets are $50 and must be bought in advance.

If you enjoy the monthly content in Hour Detroit, “Like” us on Facebook and/or follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates.

|

|

|