UPDATE: Hear Mark Kurlyandchik discuss this story on 101.9 WDET-FM’s The Craig Fahle Show and Michigan Radio’s Stateside with Cynthia Canty.

A winged throng — as thick as mayflies swarming a streetlight — circles the rural horizon in northern Macomb County. “Flying rats,” Terry Nichols says of the cloud of seagulls, turkey buzzards, and red-tailed hawks that circle incessantly, their squawks nearly drowning out the cautionary beeps of a reversing truck preparing to dump its load of solid waste. The birds — nature’s recyclers — seek their share before a compactor mashes the fresh arrival, mostly from Canada, into the growing heap.

At Pine Tree Acres Landfill in Lenox Township, this scene plays out more than 300 times a day. Perhaps more remarkable is the beauty that surrounds the buzz of activity, which occupies a relatively small portion of the 457 acres that constitute Michigan’s largest landfill.

“It’s a pretty cool view,” Nichols, the site’s manager, says from behind the steering wheel of his work truck, which is perched atop the landfill’s peak some 200 feet above its surroundings. “Those trees are just beautiful,” he says, pointing out the windshield toward the tawny landscape below, resplendent in sienna and crimson on this mid-October day.

Much of the nearby scenery is provided by 100 acres of Wildlife Habitat Council-certified wetlands, more than a third of which Waste Management reconstructed in 1998 after it assumed operation of the landfill. It’s now home to deer, muskrat, frogs, and a variety of waterfowl, all monitored by the company through observation journals and semiannual species inventories. “We’ve got bat houses up, and wood-duck houses in these wetland areas,” says Kathleen Klein, Waste Management’s local community-relations representative. From the back seat of the truck, she gestures toward a cluster of beehives to the west: “One of our employees is a beekeeper.”

This isn’t uncommon for a Waste Management landfill. In 2007, the company set a goal, Klein says, to maintain 100 Wildlife Habitat sites by 2020. That goal was reached 10 years early, and the company now protects more than 26,000 acres across the country. It’s not exactly what one would expect from the largest waste service provider in America, but it’s indicative of the changing face of the industry.

OLD GARBAGE

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says Americans generated about 250 million tons of trash in 2010, roughly the same weight as a MacBook Pro per person per day (more than 1,600 pounds per year). Where does all that garbage — or municipal solid waste (MSW), as the industry calls it — go? More than half went to landfills.

There were an estimated 20,000-plus open dumps and unlined landfills in the United States in the 1970s, an era when about 90 percent of garbage was landfilled. At the outset of that decade, President Richard Nixon created the EPA. Six years later, Congress enacted the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, establishing stricter federal laws for the regulation of waste disposal, making open dumping illegal. Implementation of it was slow, and Congress expanded its scope in 1984. By 1988, the number of landfills in the country had shrunk to fewer than 8,000.

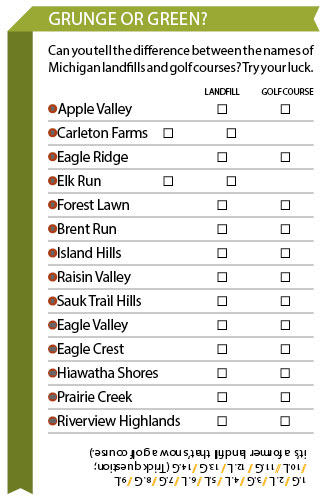

“Right now, we have 49 municipal solid-waste landfills in Michigan. That number has been steady for a number of years,” says Margie Ring, the solid-waste engineering coordinator for the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), which regulates the state’s landfills. “There was quite a bit of contraction in the ’80s and ’90s as we closed all the old open dumps and got down to more regional, large facilities.”

“In Macomb County, you had 40, maybe 50 landfills scattered around,” says Tom Horton, Waste Management’s vice president of public affairs for the Midwest. Today, Pine Tree Acres is the only one left.

That doesn’t mean we’re producing less waste. Since 1960, national MSW generation nearly tripled, dropping just slightly in the past few recessionary years. “The waste hasn’t disappeared,” says Paul Sgriccia, Golder Associates’ U.S. Waste Sector Leader and chair of the Engineering Society of Detroit’s Solid Waste Technical Conference (he is also the engineer who permitted Pine Tree Acres). “But the landfills have become larger, more regional facilities. The operators are much bigger companies that are well-financed. It’s a highly regulated industry, and these larger companies certainly understand those regulations and operate accordingly.”

Modern landfills are far from just holes in the ground. From the bottom, a 10-foot-thick natural-clay soil barrier is topped with 2 feet of super-compacted clay. “If you put a drop of water on that compacted clay and come back in a thousand years, you’d be able to catch it in a cup,” Horton says. Next comes a high-density polyethylene liner, followed by a leachate collection system. (Leachate is the liquid, mostly precipitation, that passes through the waste.) A landfill the size of Pine Tree Acres produces 60,000 to 100,000 gallons of leachate daily, enough to fill three to four standard swimming pools. Most of it is recycled back through the landfill; research has shown this expedites the waste-degradation process. The remaining leachate is hauled to a wastewater-treatment facility.

In accordance with MDEQ regulations, Pine Tree Acres monitors surface water of the surrounding wetlands and retention ponds, groundwater, and air emissions. Sixteen groundwater wells are scattered around the landfill, and more than 250 gas-collection wells suck the methane, carbon dioxide, and other gases created by decomposing waste out of the landfill. The actual space where trash is unloaded every day is kept to a confined area and covered every night by tarps or 6 inches of dirt. All of this is subject to quarterly inspections by the MDEQ.

“I think people would come away with a very different understanding if they visited a landfill,” Sgriccia says. “The amount of technology that’s used during construction and design and operation … is amazing. If I showed you the construction documentation on a 5- or 10-acre cell that’s just been constructed, you’d be amazed at the amount that’s required to submit to the state for review.”

The costs of such advanced engineering add up. On average, it takes $500,000 to prepare an acre of landfill space for garbage. That doesn’t favor small operators. “You don’t see a lot of new companies trying to site a landfill,” Sgriccia says. “I don’t think there’s been a new landfill sited in Michigan in a long time.” It has been since 2001, Ring says.

“You start your day bidding on a job against Waste Management. Then, no matter who gets the job, that waste is going to end up in a Waste Management landfill,” says Matthew Naimi, of Detroit’s community recycling program, Recycle Here!. “The ‘big four’ waste-hauling companies own 90 percent of the landfills in the United States.”

Houston-based Waste Management is the largest of its kind, servicing more than 20 million customers, with annual revenues of around $13 billion. “It’s the one business that — when you stop and think about it — we touch every person as a customer in the country every week, in one way or another, through recycling or recovery or disposal,” Horton says. Along with Republic Services, the nation’s second-largest waste-management provider, the companies handle more than half of all the garbage collection in the country.

GARBAGE IN, GARBAGE OUT

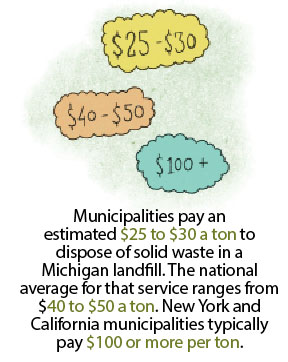

Michigan has some of the most stringent waste-management laws in the country, but it’s still one of the cheapest states to dump in, says Milind V. Khire, associate professor of geotechnical and geoenvironmental engineering at Michigan State University. Khire says average tipping fees (the money haulers pay to dump their waste at a landfill) in Michigan are about $25 to $30 per ton for MSW, while the national average is between $40 and $50. “In New York and California, it’s more like $100 to $150 per ton,” Khire says, “because the land is expensive.” And the State of Michigan takes only a 36-cent per-ton surcharge from the haulers. Wisconsin levies a $13 surcharge for the same amount.

As a result, Michigan ranks third in out-of-state trash imports, most of which come from Canada. “We border one of their most populated provinces,” Khire explains. “Canadian environmental regulations are even more stringent than U.S. regulations, so the landfills in Canada are more expensive. Transporting the waste across the border, going 200 miles, and disposing in Michigan at a cheaper rate, is still a more economical solution than putting it into a Canadian landfill.”

Mike Garfield, director of the environmental advocacy nonprofit The Ecology Center in Ann Arbor, offers another reason for the low fees: “In the 1990s, the state allowed far more landfills to be sited and developed than we really needed for our purposes in Michigan. As a result of that, the price of discarding waste in Michigan, and particularly southeast Michigan, plummeted. The impact of that is that Michigan became something of a dumping ground for much of the Midwest.”

But there’s another side to the equation, Horton says. For one, Michigan ships much of its hazardous waste to Canada. And what we trade in landfill capacity, we are awarded with in new technologies that stem from Canada’s aggressive advancement of landfill diversion techniques. “The benefit that we got from Canada was that they put hundreds of millions of dollars into the early technology of gasification, the organic digesters, all of the things that we can see in the next decade are going to be technologically viable [waste management practices],” Horton says. “I think it’s a reasonable trade.”

Trash importation brings up another important issue: landfill capacity. Every year, the MDEQ issues a report on solid-waste imports, which is used as a baseline for estimating remaining capacity. According to the most recent report, issued in February 2012, Michigan landfills collectively have 24 years of remaining disposal capacity. Cause for alarm? Horton doesn’t think so.

He takes issue with the official capacity number, explaining that it accounts only for currently permitted cells. (The MDEQ grants permits on a cell-by-cell basis after each one is prepared to receive waste. A cell is roughly 15 to 20 acres.) A site such as Pine Tree Acres, with a current permitted waste footprint of 283 acres, has an estimated remaining capacity of 12 to 13 years. But Horton says this number doesn’t take into account all the approved, but not yet permitted, area that hasn’t been developed into cells, nor the property surrounding the landfill that Waste Management owns but hasn’t considered or applied for permits on. “There is no crisis,” he says. “We don’t need any more capacity if we develop the existing capacity that we have. We have plenty of capacity for the next 50 years.”

Because the MDEQ’s calculation is based on annual reports, that number could rise if current trends continue. Since 2010, when Toronto stopped shipping its waste to Michigan, inbound Canadian waste has decreased significantly. At its peak in 2006, Canadian waste comprised nearly 20 percent of all solid waste disposed of in Michigan landfills. Last year, that number was closer to 15 percent. Also, Michigan-made solid waste has been steadily decreasing since 2003 (with the exception of a slight increase from fiscal year 2010-2011), and so has waste imported from other states.

“We’re seeing waste going into landfills trending down with time,” Ring says. How much of that is thanks to recycling and other efforts and how much is due to the sluggish economy is hard to measure, she says. “There’s a lot less construction, there’s less manufacturing, and just less consumerism. I think that’s part of the decline, as well.”

By implementing some waste-degradation acceleration processes, such as reintroducing leachate back into the landfills, as Pine Tree Acres and many others now do, Khire estimates we could add another 30 to 40 percent of capacity without actually expanding landfills’ geographic footprint. But he disagrees with Horton about the remaining space. There will be a point of critical mass, he says, unless there’s a larger paradigm shift. “I think we are buying more time,” Khire says. “By buying more time, we’re going to get more time to develop technologies that will essentially replace landfills.”

The Anatomy of a Landfill

WASTE NOT

“The biggest problem with [landfills] is that they waste good resources that, if handled correctly, can be reused, salvaged, or recycled and made into usable products in ways that create jobs and bolster the economy,” Garfield says. “Landfills are vestiges of the early 20th century that we have modernized and regulated, but it’s still an antiquated and inefficient way of handling trash.”

Horton points to the shifting culture within Waste Management as evidence that change is afoot. “We used to go to our customers and say, ‘How much trash do you generate?’ We’d size containers and services based on that,” he says. “Now we go in and say, ‘Tell us a little bit about your business. What are you generating here?’ ”

Beyond changing the sales pitch, the company also adopted a wide range of sustainability goals in 2007 for recycling, renewable-energy generation, energy efficiency, and land conservation, the latter of which covers the Wildlife Habitats. Waste Management is also the country’s largest recycler and produces more renewable energy than the entire U.S. solar industry.

At The Wall Street Journal’s ECO:nomics conference last spring, Waste Management CEO David Steiner spoke about the company’s changing business model, which is moving away from landfills and toward transforming the garbage into material with a more lucrative margin. “If we can take that material that our competitors take and make $20 a ton by putting it into a landfill, if we can convert it to energy, if we can convert it to oil, if we can convert it into a specialty chemical and make $100 a ton on it, the game’s over,” Steiner told The Wall Street Journal.

“Our corporation, hearing what our customers are saying, knows that every yard of material that we put into the landfill and fail to extract the material out of is a yard where we’ve simply lost today,” Horton says. “We’ve lost the value of that material. The goal is to develop the technologies where you can take this mixed solid waste and get the value out.”

The future of waste management, Horton says, is in new technologies and start-ups that his company has invested in and partnered with, such as Agilyx, which converts difficult-to-recycle industrial and consumer plastics into synthetic crude oil. There are about 30 other similar investments that Waste Management is interested in — all with one goal in mind: diverting the material from the landfill for a greater profit.

“Someone once asked me, ‘When is Pine Tree going to close?’” Horton says. “And my answer is that it’s never going to close. … It’s going to evolve into a processing facility. There’ll be a single-stream processing facility here for recyclable materials. There may be something here that takes tires and processes them into a waste stream.”

For now, much of the focus is on landfill gas. In June, Pine Tree Acres held a dedication event for its new $15-million landfill gas-to-energy plant, which converts the methane that’s collected from the landfill into enough energy to power about 12,000 homes.

Although Horton says Waste Management is changing to meet the demands of its consumers, sometimes it is because it’s pushed in that direction. The new gas-to-energy operation exists at least in part because of a class-action lawsuit filed by nearby residents in Lenox and Casco Townships, who claimed an “intolerable … sickening odor” and “blowing debris” were causing a public nuisance, alleging negligence and violations of the Michigan Environmental Protection Act. The case was settled in 2009 for nearly $19 million, and the new plant improvements for boosting gas-to-energy capacity, which decreased the amount of gases that would have simply been burned in the landfill’s stacks, was part of a good-faith commitment to the community.

“Landfills are such a damaging burden on communities, that there’s no way to win political support for a landfill in your backyard unless the company developing the landfill is willing to do an awful lot of favors for that community,” Garfield says. “It’s really hard for a developer to get a township’s support without providing financial support to the community, usually millions of dollars worth of incentives.”

In the case of Pine Tree Acres’ host-community agreement with Lenox Township, it pays about $2 million annually in donations and in-kind services, which have paid for miles of new public water lines, a new fire truck, a grant for public park signs, and the rebuilding of a major intersection. That doesn’t include the $1 million in taxes it pays each year, too.

RECYCLED FUTURE

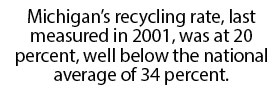

Michigan has its recycling challenges. For starters, there hasn’t been a comprehensive study of the state’s recycling rate since 2001, when the Michigan Recycling Coalition conducted one using federal grants from the EPA. That study showed Michigan’s recycling rate (20 percent) lagging behind the rest of the country (34 percent). Horton discounts the accuracy of that statistic, citing its age and the increasing popularity of recycling.

Kerrin O’Brien, the director of the Michigan Recycling Coalition, says that it’s possible that the rate has actually dropped. “BioCycle magazine does the state of garbage report, and they actually indicate that we’re doing less than we were in 2000,” she says.

That poses environmental and economic costs. “If we were to reach 50-percent recycling … that would mean $492 million in the value of materials,” O’Brien says. “Right now, we’re paying to put that material in the landfill.” She says significant progress can’t happen without a change in infrastructure that shifts the focus from supporting landfills and incinerators to recycling and other diversion tactics. To get the state to that 50-percent target would cost approximately $76 million, she says. “We’re working very hard to help policymakers understand that there’s this value equation, and what we need to do is fund it.”

Khire underscores the importance of policy. “Government has to come up with the pathways, and the private sector will take over automatically,” he says. “The private sector just can’t make it financially work now.” Horton echoes that sentiment and cites the positives of the Clean, Renewable and Efficient Energy Act of 2008. It says 10 percent of Michigan’s energy should come from renewable sources by 2015. Unlike Proposal 3, which sought to require 25 percent of the state’s energy to come from renewable sources by 2025 — it was defeated Nov. 6 — the 2008 policy is not a constitutional amendment. Both efforts require utility companies to get energy from renewable sources, including landfill gas.

But policy is just one leg of the stool. In order for recycling to be successful, there needs to be a market to support it, and a degree of personal responsibility. For Garfield, it’s an issue better tackled at the community level. His Ecology Center founded Michigan’s first recycling program in 1970, the same year the EPA was created. “When you have well-constructed programs, like we have in Ann Arbor and a few other communities in Michigan and other parts of the country, you can generate a good amount of economic activity, protect the environment, and do well financially at the community level,” he says. “I don’t think it’s very likely that we’ll see good public policy changes in the near term. But I do see a lot of interest at the local level, and communities making changes.

“Even Detroit, where you’ve got more difficult budget problems than almost anywhere in the country, they’ve put in place a pilot curbside-recycling program in the last few years. What we’ve found when we’ve analyzed the finances of Detroit’s system is that they could save money in the city’s budget by investing more heavily in recycling.”

ONE MAN’S TRASH

“I think someday in the future, somebody will come in and mine all this,” Nichols says as he maneuvers his work truck down the face of Pine Tree Acres.

“It all ties into the commodities,” Horton adds from the back seat. “They say that 3 to 4 percent of the volume in landfill sites is precious metals. There are other commodities in here. … Maybe 40 years from now, these are going to be mined just like a coal mine.”

That evokes a slightly absurd image: an excavator clawing through layers of soil, disposable diapers, grocery bags, newspapers, broken vacuums, Styrofoam carryout containers, plastic water bottles, and other fallout from a more disposable former culture, all in the hope of finding some aluminum mattress springs or copper wiring.

You can tell a lot about a person by what he or she throws away. What story do our landfills tell?

“I believe our kids and our grandkids will look back 50 or 100 years from now and say, ‘What were those people thinking?’ ” Garfield says with a chuckle. “Why were they throwing good stuff into a hole in the ground?’ ”

Garbage Disposal

>> From Thanksgiving to New Year’s Day, household waste increases by more than 25 percent.

>> The 2.65 billion holiday cards sold annually in the United States could blanket a football field with 10 stories of paper. If we each sent one less card, we’d save 50,000 cubic yards of paper.

>> Each year, 50 million Christmas trees are bought in this country. About 30 million end up in a landfill.

>> According to the Michigan Recycling Partnership, increasing recycling in Michigan from 20 percent to 30 percent would create between 6,810 and 12,986 jobs, generate $155 to $300 million in income, $1.8 to $3.9 billion in receipts, and about $12 to $22 million in state taxes.

>> Michigan has 49 Type II MSW (municipal solid waste) landfills and 23 Type III (low-hazard industrial waste or construction-demolition waste) landfills.

>> Nearly 46 million cubic yards of solid waste were discarded in Michigan landfills in fiscal year 2011. Waste generated in Michigan increased by about 3 percent from the previous year, while total imports of waste decreased by about 12.8 percent.

>> Plastic can take 1,000 years to degrade in a landfill. A banana takes four weeks.

>> The United States produced 827,000 to 1.3 million tons of plastic PET water bottles in 2006, requiring the energy equivalent of 50-million barrels of oil.

>> More than 20,000 unlined and open-dump landfills existed in the United States in the 1970s. Today, there are about 1,900 permitted and licensed landfills in the country.

>> Some 250 million tons of municipal solid waste were generated in the United States in 2010. About 136 million tons went to landfills.

Sources: EPA, Michigan DEQ, Institute for Self-Reliance, Clean Air Council, Michigan Recycling Coalition, Be Straw Free, RecycleWorks, Gone Tomorrow: The Hidden Life of Garbage.

|

|

|