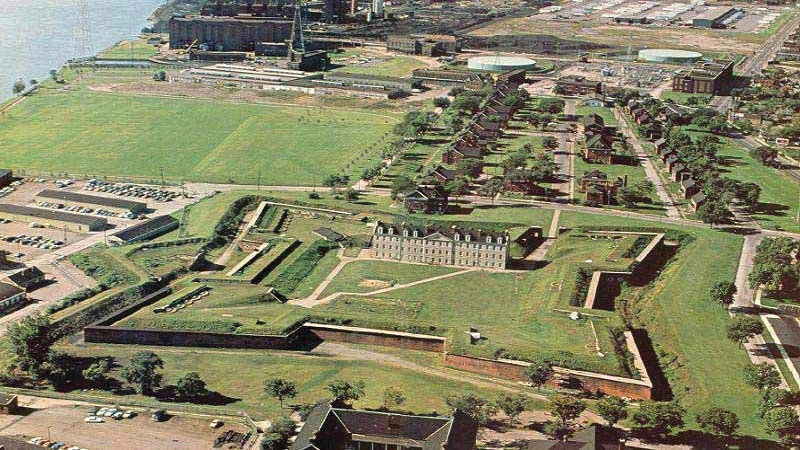

For its first 1,000 years or so, the area along the banks of the Southwest Detroit riverfront now known as Historic Fort Wayne was a site of perpetual human activity. Whether it was a burial site for indigenous tribes, a star fort poised to defend the United States against a possible Canadian invasion, or a refuge for Detroiters burned out of their homes by the 1967 Rebellion, the 78-acre tract of sprawling fields and historic buildings has rarely sat idle.

Until the last few decades, that is. Most of the property’s more than 40 buildings are vacant and falling into disrepair. Various redevelopment proposals over the years have foundered, in part because National Park Service regulations put the kibosh on them.

The latest effort, though, seems real. The City of Detroit Parks and Recreation Department, which oversees the site, has struck a deal with NPS to allow for development while providing guarantees to maintain the fort’s historic integrity. With that roadblock gone — and knowing the City of Detroit is unlikely to put up the sort of investment necessary for a full restoration — the department has laid plans for an innovative “rehab-in-lieu-of-rent” model.

That is, rather than the city handling the project or selling out to a major developer, Detroit will divvy up the property, leasing individual buildings to a variety of organizations and companies. Fort Wayne will remain a cohesive unit, operating as a network of small adaptive-reuse projects, with tenants paying to remodel the spaces and the costs being deducted from their rent. A full redevelopment is likely to take a decade, Chief Parks Planner Meagan Elliott says.

“This is an opportunity to unlock the potential of Historic Fort Wayne,” Elliott says. “I imagine it can be one of the shining jewels of our city, in the same way that Belle Isle and the Riverfront are. It’s a place to show off much of what’s beautiful about Detroit.”

The city isn’t totally off the hook. Detroit will beautify the parade grounds and handle immediate repairs required to prevent even pricier long-term challenges. And the city’s parks department will highlight the fort’s illustrious history by developing informational signage in collaboration with the Detroit Historical Society.

That history dates back to medieval times, when there is archeological evidence that indigenous peoples buried their dead there in mounds. In 1701, French colonists established a trading center on the grounds. After the American Revolution, it became a military installation named after General Anthony Wayne, hero of a 1796 battle against the Native Americans near Maumee, Ohio, that preluded the U.S. occupation of the regions that now make up Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and a piece of Minnesota.

Fort Wayne never saw battle, but it served as a primary induction center for Michigan troops serving in U.S. conflicts, from the Civil War to Vietnam. After that, it was an infantry training station, a procurement base for Detroit-manufactured vehicles and weapons, and even a bastille for prisoners of war.

Five applicants have expressed interested in joining the fort’s current tenants, which include the Detroit Historical Society, the Tuskegee Airmen National Museum, and the Historic Fort Wayne Coalition. Among the possible new arrivals is a partnership between Detroit Rising Development and Grand Circus Media to turn stables into an indoor-outdoor concert venue and brewery, as well as C.A.N. Art Handworks and the Southwest Detroit Business Association, which hope to establish a skilled trades training center and a museum focused on the region’s Latinx community. In addition, the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi is looking to take ownership of the existing Great Lakes Indian Museum and remaining burial mound as cultural sites.

The James Oliver Coffee Co., which relocated from New Hampshire to metro Detroit in November 2019, is also taking an interest. Its product is served at several local eateries, and co-founder David Shock wants to relocate the roastery’s site at East Davison Street and Mt. Elliott Street on Detroit’s east side — an area that Shock calls “the middle of nowhere” — to Fort Wayne, where he would also add a café.

“I drive by the property every once in a while, and never feel like I’m in the city of Detroit,” Shock says of the fort area. “It’s so surreal, and it would be nice to be someplace kind of magical.”

The selection of tenants will take a while, though. Each must submit a business plan, and the department will seek input from the surrounding community before making recommendations to the city council. In fact, Elliott says, community engagement is key. The planning team assembled an advisory council of locals, neighborhood organizations, and area tribe members. The parks department has already turned down applicant requests for large chunks of the property’s buildings to ensure the fort comprises local businesses and organizations.

Elliott says she and her team are setting out to create something that belongs to the community: “There’s so much diversity of people and of interests in the neighborhood, and we wanted to reflect that.”

|

|

|