What does it take to be a doctor in the 21st century? The Affordable Care Act has spurred significant changes in how medical schools train future physicians, and those changes couldn’t come at a more critical time.

What does it take to be a doctor in the 21st century? The Affordable Care Act has spurred significant changes in how medical schools train future physicians, and those changes couldn’t come at a more critical time.

Michigan’s shortage of primary care physicians is projected to reach 4,400 by 2025. The state has an estimated 29,800 physicians, with a quarter of them age 60 and older, according to a report prepared for Michigan Health Council and Medical Opportunities in Michigan.

And there’s a projected shortfall of 2,000-8,000 for all specialties by 2020, according to the Annals of Family Medicine.

Some experts say that reform offers a pivotal opportunity to improve the health care system. They’re calling on medical schools to prepare the next generation of doctors in not only the sciences, but also in how those future physicians connect with patients on a human level.

And some of that next generation are being trained right here in Southeast Michigan.

Even though Beaumont Health System has been teaching residents for 55 years, it wasn’t until seven years ago it signed a letter of intent with Oakland University to begin the accreditation process for forming a new allopathic (traditional M.D.) medical school.

The Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine (OUWB) was formed in part to combat the projected physician shortage in Michigan.

Since then, two other Michigan schools have also stepped up to alleviate the 90,000 doctor shortage the entire country will face by 2020: Central Michigan University College of Medicine opened in August of 2013, and Western Michigan University School of Medicine started this August.

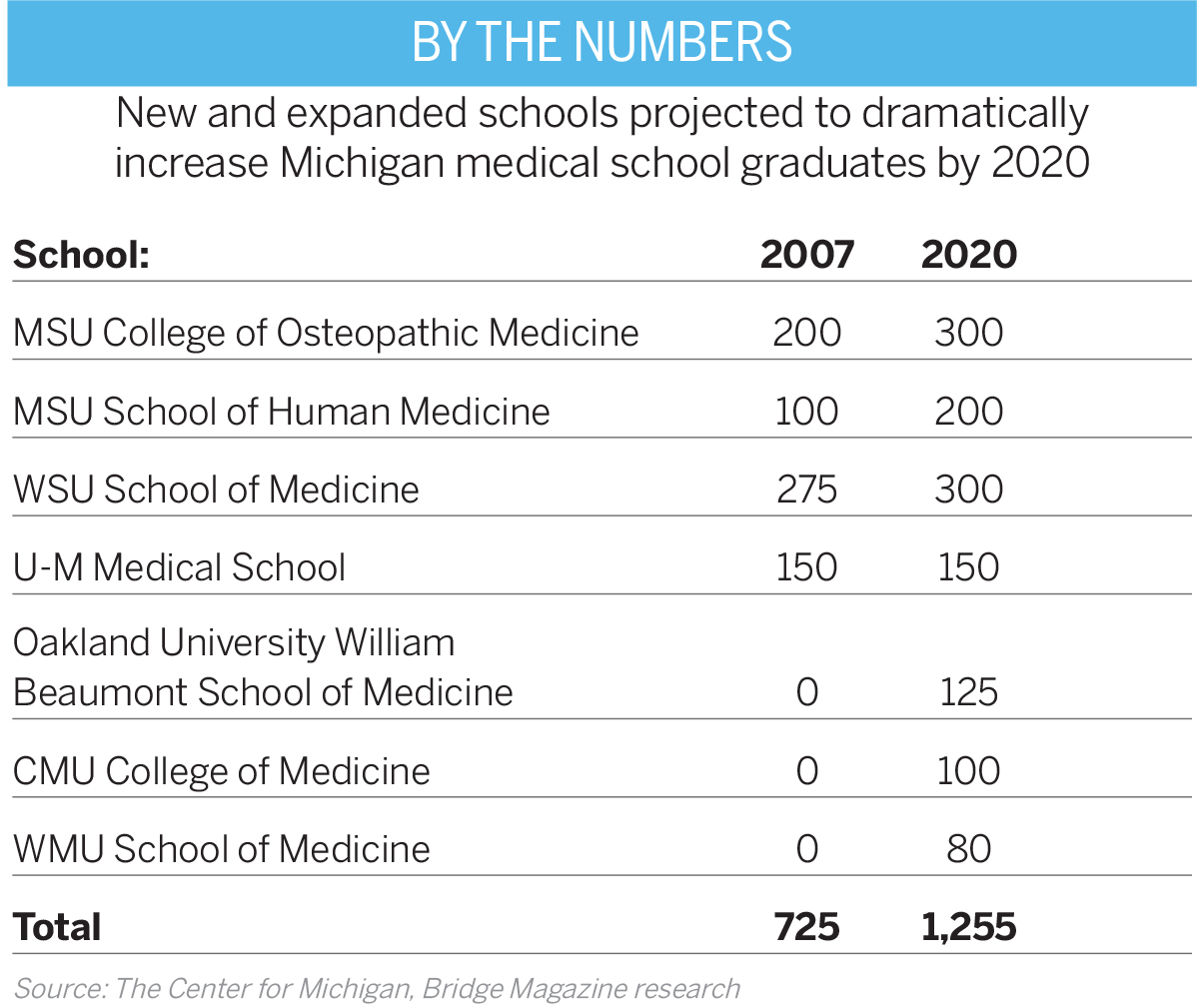

With the addition of three new medical schools, Michigan will be graduating about 1,250 medical school students a year by 2020 — an increase of 73 percent in a decade, according to the Center for Michigan’s Bridge Magazine (see table).

“We are designed to complement the legacy of the already existing medical schools here in Michigan,” says Robert Folberg, M.D., the founding dean of OUWB.

But the vision was also to help transform medical education. “We are one of 17 new medical schools [nationwide] since 2005,” says Folberg. “And we are all charged with innovating and developing a physician not only scientifically and technically smart, but also someone who is a good communicator and listener.”

Joining OUWB’s First Class

Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine’s charter class will graduate next May. The first class was purposefully small — with only 50 students. Class sizes will increase by 25 students, with a cap of future class sizes at 125, to emphasize team-based, integrative instruction in small groups.

Hand-picked out of more than 3,200 applicants, 70 percent of the charter class came from Michigan, and they all began their journey on Aug. 8, 2011.

Gone are the days where medical school admissions solely rely on rankings and test scores. OUWB uses a holistic process to fulfill its mission: to turn medical students into a physician who’s not only competent, but also is compassionate, listens with focused intensity, and communicates clearly and with an elevated level of cultural awareness.

OUWB has a full-day interview event for both administrators and students to meet and decide if the school is the right fit, says Christina Grabowski, assistant dean for medical school admissions and financial services at OUWB.

It was a beta site to host the Holistic Review Project workshop, a new method of admitting students that’s run by the Association of American Medical Colleges. It’s designed to assist medical schools in enhancing student body diversity by giving a balanced consideration of life experiences, goals, and academics, Grabowski says.

Medical schools everywhere are putting a higher emphasis on admitting a well-rounded student with volunteer experience and a variety of other unique factors.

The charter students seem to like the approach.

“I chose Oakland to be a founding member of something new, and the atmosphere of the school right from interview day felt almost like family,” says charter class student Anne Wagner. “Dean Folberg actually came and spoke to us on interview day and that was really unique to meet the dean of the medical school — not at any other [medical school] interview did I meet the dean.”

“The first thing that drew me to the school was my interview there,” agrees fellow charter student Andrew Angus. “I felt like the whole interview process was more of a ‘get-to-know-you’ type of session than a stressful ‘grill you’ type of interview.

“Med school is already stressful enough so you don’t want to have to deal with the frustration of the administration too,” Angus adds. “They seemed genuinely excited to meet us.”

A New Curriculum for a New Generation

Folberg says that even without the impending doctor shortage, OUWB would have set out to change the way doctors are trained.

“None of this shortchanges science,” he says. “The science curriculum is very strict here. But for too long medical education has been focused on knowledge and technical training, and people have to understand patients are neither problems to be solved nor data repositories to be mined — patients are people in need.”

OUWB’s curriculum parallels the main points found within the American Medical Association’s 2007 report, “Initiative to Transform Medical Education.” It discusses in-depth about the need to create a system of medical education to better equip young physicians with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values necessary to provide quality and compassionate medical care.

“How physicians learn to connect with patients at a human level is the cutting-edge component of medicine in the 21st century,” says OUWB Professor of Bioethics Jason Wasserman, Ph.D. “I think the way most institutions deliver ethics, humanism, and even the social sciences is far less than optimum, and they’re not built into the curriculum in a way to allow you to have a robust understanding of those things … And here [at OUWB] it is.”

One example is a class called The Art and Practice of Medicine. “We don’t just start teaching them to actually interact with patients right before they enter the hospital,” Folberg says. “We actually test them on patient skills at the end of their first semester, which is very unusual.”

Who is doing the teaching also matters. And doctors came to Michigan from across the country to specifically join Beaumont Health System in anticipation of the new medical school, including Dr. Alan Koffron, Beaumont’s chair of surgery.

In 2008, Koffron came from Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago where he was the medical director of the Living Donor Liver Transplant Program and associate professor of transplantation surgery at Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University Medical School.

“Moving my career to Michigan was based on two obvious factors,” Koffron says. “First, Michigan is a wonderful state, with enviable nature and outdoor opportunities, populated by kind Midwest people like I knew growing up in Iowa. Second, I was given the unique opportunity to practice in a second-to-none health care system, and a new, innovative medical school, staffed by these same people who take care of patients with sincerity and a unique loyalty.”

Then there are other doctors like Brian Berman, physician-in-chief at Beaumont Children’s Hospital, who came in 2012 from Children’s Hospital in Cleveland. He was also a professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University.

Berman says that as a Beaumont physician he also feels a burgeoning responsibility to take care of OUWB students.

“By watching us we’d like to think the graduates will not only be superior physicians by conventional measures, but also people who are in medicine for all the right reasons,” he says. “I may be a bit of a romantic, but I still consider medicine to be more than a profession, more of a life choice, a calling.

“I came from a very fine institution,” Berman adds. “But there’s no question in my mind that Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine is at a very high echelon.”

The ease of student access to the network of physicians, faculty mentors, and people at Beaumont Health System seems to be the overarching point of importance that has made the biggest difference for the first graduating class.

New Tools and Skills

Medical students need access to the latest technologies too.

“They’ve given me access to the surgical learning center, to the chief of surgery, and most medical students never get a chance to use [equipment like] the da Vinci robot or the simulator for that matter,” Angus says.

Students are also being prepared to treat patients in the most timely, efficient, and effective ways. For example, best practices for mastering the inevitable boom of electronic medical records (EMR) are taught from the beginning. It is mostly a matter of experience when finding the perfect balance between interacting with patients compassionately, while also interacting with a laptop, iPad, or other electronic device. Board exams, a set of national exams all future physicians must pass, also stress the importance of time spent with a patient. Many tests allow a mere 15 minutes to figure out what is wrong, do the actual physical exam, and counsel the patient. An additional 10 minutes is allocated to complete the entire write-up for the patient’s file.

“With everything transitioning to electronic medical records, it’s not just the learning curve of using them, but being able to communicate when you have a computer screen in between you two,” Angus says. “I think that is the future of doctor, patient relationships.

“It is important to be able to convey empathy while staring at a computer screen; you have to know how much time should be spent with the patient,” Angus adds. “And that takes a lot of skill and patience.”

To help learn interactive skills, first- and second-year students participate in simulated patient lessons, and also get the opportunity to go into the hospital and see actual patients, as well as visit homebound patients with nursing school students to get to know patients more on a personal level.

“I really liked how we could start our clinical training early on; I thought it really prepared me for my third-year clerkships,” says Wagner. “The culture of Beaumont and OUWB really focuses on empathetic patient care.”

A Community Approach

The first class of students about to graduate next spring was able to help shape the way the school’s community feels like, and high expectations have been set. Walking on campus, faculty members refer to students by name, and there are approachable-size lecture halls with state-of-the-art education technology — it could almost be described as a medical school with a liberal arts college feel.

Students like Angus helped choose what student activities are available; he helped start the surgery interest group. The partnership between Beaumont Health System and OUWB has expanded the group to an entirely new level, allowing the chief of surgery to offer students advice and connections they otherwise wouldn’t have access to.

“I was the founding vice president for the surgery interest group and we got to work closely with the chief of surgery, Dr. [Alan] Koffron — that was huge,” Angus says. “Working with him we were able to make it more than just a regular, run-of-the-mill surgery interest group where there’s a pizza party once a month. But we are actually forming a surgery society that will also include the residents at Beaumont as well.”

Charter class student Amanda Xi also wanted to be a part of creating a new culture. She became the founding president of AMWA, the American Medical Women’s Association. There are hundreds of branches around the country, but in the founding year, 2011, as well as the year after, OUWB’s branch earned national recognition with a Heller Outstanding Branch Award, in a pool of candidates also including Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University, and George Washington University.

Xi formed activities in the first year that AMWA continues to participate in — like Dinner with a Doctor, where students meet with a physician who is in a specialty they are interested in to share advice and goals with one another over dinner.

“There’s a lot of road bumps and barriers that you don’t expect when you are starting an organization,” Xi says. “But something like Dinner with a Doctor, it helped me connect with a lot of women physicians within the Beaumont Health System, and a lot of them have been welcoming or encouraging if I have questions or need connections.”

Capstones and a PRISM focus

Other enticing parts of OUWB’s curriculum for many students are The Capstone Project and PRISM (Promoting Reflection and Individual growth through Support and Mentoring).

Capstone is a required four-year research project. Students are paired with a faculty mentor and choose a topic of personal interest to research an independent, hypothesis-driven project. Every med school has a research requirement, and OUWB isn’t claiming to be the next research-intensive school like U-M Medical School, but they are pushing students to research outside the classroom — and students are loving it.

“The way we do Capstone is being spoken of as a national model,” Folberg says. “It’s because we teach people how to properly research what they do, but then we cut them loose and they can follow their own passion.”

Xi is a prime example. She began blogging about her experience as a student applying to medical school and slowly expanded her social media presence. Her Capstone Project focuses on social media policies at U.S. medical schools.

“A previous study … found only 10 percent of med schools had any policy at all,” Xi says. “With how much social media has exploded over the years, I did find a substantial increase in the percentage of schools that had formed social media policies, but I was surprised it’s still not at 100 percent.”

Florence Doo, part of the 2017 class, came to OUWB after getting her undergraduate and master’s education at Wellesley College and Boston University, and was looking for a school that would allow her to research a variety of topics in a flexible environment.

“I was looking for a place that would be very encouraging for new projects, and encouraging innovation in their students. They had this Capstone Project at the time that I was really engaged with and it was an area that had a lot of potential,” Doo says. “A lot of schools are very entrenched and don’t have that flexibility, and the fact that they were not only having this program, but being very encouraging about it was a big reason why I chose OUWB.”

Doo found that the flexibility and focus on research at OUWB allowed her to win two national competitions, one being at Google headquarters in Boston during a “pitch-off,” where she presented her software idea, “the FoveOR,” which eliminates distractions in surgery by integrating software with Google Glass to transmit essential radiographic images to the operating room surgeon wearing the glasses. She was the first and only medical student among the 13 finalists, and won the Freedom Nation Award.

Then there are students like Angus, who has had a life goal of becoming a surgeon, but admitted he never thought he would’ve pursued clinical research as a student unless it was built into the program. As a commissioned officer in the United States Air Force under the Health Profession Scholarship Program, Angus recently spent time in Mississippi on active duty for a surgical rotation.

The PRISM approach and Capstone work hand in hand beyond being part of the required curriculum. “Through my PRISM mentor I met the general surgeon who helped me devise my Capstone Project, and now I’m doing three different research projects on robotic surgeries … I’ve even gotten published,” Angus says. “Capstone opens doors to be able to do the research you want to do versus what you have to do, and you might even stumble across something fun, like I did.”

PRISM mentors play a major role. Once a month, or more, students meet with the same faculty mentor all four years to discuss their overall well-being, and any issues they might have, says Dr. Angela Nuzzarello, PRISM co-director.

“OUWB is also very supportive of specialty interest groups,” Xi says. “We learn a lot about the field through the specialty groups, and our PRISM mentor is an emergency medicine physician who from early on said, ‘Here is my cellphone number; text me if you need anything.’ ”

That’s where OUWB is trying to be different, by offering a number of resources and outlets for students to get advice and support. “How can we expect future physicians to really be the next generation of doctors if we don’t take their personal well-being into consideration?” Nuzzarello asks. “We’ve developed a program here that really focuses on the personal development of medical students.”

Wagner recalls how helpful her PRISM mentor — Radiology Discipline Director Dr. David Bloom — has been as well.

“I just emailed one of my personal statements to Dr. Bloom and within that day he emailed it back to me with edits,” Wagner says. “He gives us really practical advice, we talk about our struggles, and he can facilitate discussion with administrators.”

The Envelope, Please

At the time this article was written, it had been about a month since the charter students had taken a highly intimidating, nine-hour, multiple-choice “Step 2” portion of the U.S. licensing exam. All were anxiously awaiting the results since the test plays a big factor in deciding where students match for their residency.

Match Day could easily be considered just as, if not more important than graduation day, because the match handed to you in an envelope determines what hospital you will be at, for up to the next seven years.

Once a student decides on a specialty of medicine they want to focus on, they must complete a residency at a teaching hospital to be allowed to practice medicine independently. During the fall of their last year, students are encouraged to travel around the country to interview at prospective residency programs they wish to attend, to assist them when it comes time to rank all their options. Test scores and a number of factors are combined, but surprisingly, it’s a mathematical algorithm that ultimately determines where each student ends up.

“I would love to be a resident of anesthesiology at Beaumont Health System because I am familiar with how it works and feel comfortable there, but there are only four spots open for anesthesia in Michigan, so I am applying broadly,” Xi says. “It’s all up to what the envelope says.”

But wherever they end up, OUWB students feel they’re prepared.

“I think a lot of residency programs might’ve questioned the reputation it has as a new program,” Angus adds. “But the opportunities that I’ve gotten as a member of the founding class — forming different student organizations, and opportunities to present projects as part of a larger health system — have proven to be irreplaceable.”

And students at OUWB just might feel they have a step up. Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak was ranked the No. 1 hospital in Michigan by U.S. News & World Report. It is the 20th consecutive year Beaumont had earned a national ranking, and OUWB students are proud to call it their home hospital. Others are catching on too; compared to last year applications are already up by 39 percent, and the application cycle isn’t over until November.

“Being affiliated with an entire health system that is nationally ranked is something not all medical students can say they have experienced,” Angus says. “Every health system treats rotations differently, but at Beaumont we are allowed to actually become part of the resident team, and really become enveloped in the core group of people making a difference every day.”

|

|

|