The Hard Lessons’ story isn’t great because of the music they made — which was solid. Or because they eventually made it big — because they didn’t. It’s great because of how the story ends. Because of how they stopped being a band. Because they chose to quit chasing the dream they always wanted to make room for the one that’s chasing us all.

In Korin and Augie Visocchi’s Rochester home, the garage has become the last stronghold for the remnants of a former life. Even here, a decade worth of artifacts are relegated to the edges: Hanging on the wall is the cartoonish oversized check that they won at a 2004 Battle of the Bands, which wasn’t really a check but a $1,500 gift certificate to a Lansing music store. Right next to it: the once new-in-box Fender Telecaster guitar that Augie redeemed the “check” for, now so beat to sh*t it’s often mistaken for vintage by guitar enthusiasts.

The 10 stuffed Rubbermaid totes, which require a ladder and an extra set of hands to pull down from a storage loft, contain a good chunk of the archives: Hundreds of newspaper and magazine clippings, including both times The Hard Lessons were on the cover of Metro Times; the issue of SPIN, where Augie says a writer christened them the next “it” couple from Detroit; a VHS tape from the night one of their songs was used in an episode of the NBC football drama Friday Night Lights.

“That’s how old our band is — people used to VHS us off TV,” Augie says sarcastically, tossing down the tape — adding that the last time he went through any of this stuff was “a couple kids ago.”

Right on cue, the 6-year-old Santino opens the door to the garage, calling out the reminder of a promise made a few hours earlier. “Dad! We’re ready for cookies!” With that, the brief trip down memory lane is over, and we’re headed up the stairs, where the one named “Little Saint” is waiting at the dinner table ready to begin negotiations. Santino lobbies valiantly with mom and dad to eat the entirety of a five-inch diameter chocolate chip from Whole Foods, but it’s not gonna happen, and he settles with minimal whimpering on a half-now/half-later compromise plus a favor, which is requested from his father in Italian. The boy shuffles shyly over to the piano and then picks out seven notes on the keyboard. It’s not one of The Hard Lessons’ songs; or Talking Heads’ “Once in a Lifetime,” which I’m told is Santino’s go-to at karaoke nights. It’s the instantly hummable bassline from The White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army” — an unsubtle homage to the Detroit band Augie credits for giving people the feeling that if there was someone here worth listening to, there might be others.

Right on cue, the 6-year-old Santino opens the door to the garage, calling out the reminder of a promise made a few hours earlier. “Dad! We’re ready for cookies!” With that, the brief trip down memory lane is over, and we’re headed up the stairs, where the one named “Little Saint” is waiting at the dinner table ready to begin negotiations. Santino lobbies valiantly with mom and dad to eat the entirety of a five-inch diameter chocolate chip from Whole Foods, but it’s not gonna happen, and he settles with minimal whimpering on a half-now/half-later compromise plus a favor, which is requested from his father in Italian. The boy shuffles shyly over to the piano and then picks out seven notes on the keyboard. It’s not one of The Hard Lessons’ songs; or Talking Heads’ “Once in a Lifetime,” which I’m told is Santino’s go-to at karaoke nights. It’s the instantly hummable bassline from The White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army” — an unsubtle homage to the Detroit band Augie credits for giving people the feeling that if there was someone here worth listening to, there might be others.

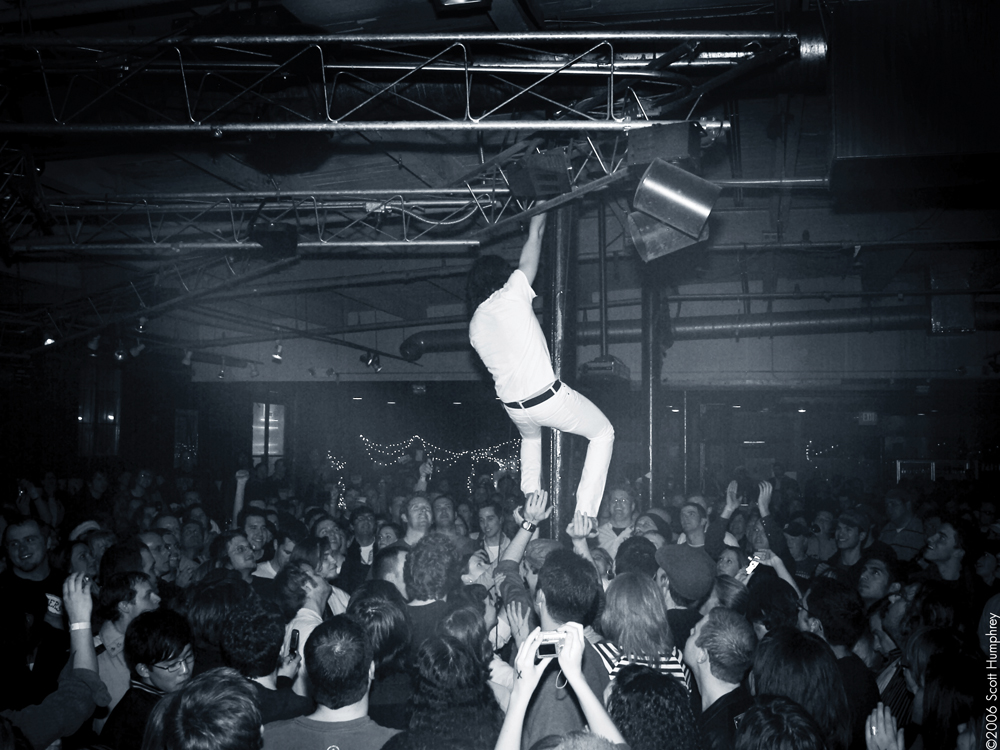

There are some who say most of what Augie and Korin got as The Hard Lessons (which had several drummers over the years) was a coattails phenomenon — fueled by the mid-2000s White Stripes mania and the country’s fierce, if fleeting, interest in Detroit’s garage rock scene. But it’s hard to argue they didn’t earn some of it themselves. If you saw them live, you witnessed it. If you didn’t, the YouTube videos show well enough what the band was known for: A live stage show where Augie, the frontman of the duo, methodically obliterates the lines that divide band and fan and whips the audience into a sweaty, yelling, feel-good mob.

Sometimes the techniques are subtler, as you’ll see in a video of “Carey Says” at Hamtramck’s New Dodge Lounge, where a shouting call-and-response eventually evolves into a full-on sloppy singalong. In another, the tactics are more circuslike — as when Augie straps his guitar to an exposed water pipe lining the ceiling of the club, then shoves the instrument out for the crowd to play. There were occasionally broken teeth and broken ribs, but always, night after night, a high-volume, organized frenzy of fan-to-fan, fan-to-band togetherness. Augie says even some of their naysayers conceded that “their band sucks, but they’re great people.”

Some thought his stagecraft was too kitsch, even rehearsed. It might be more accurate to say it was learned, internalized, and earnestly echoed. “I came from an immigrant family; I didn’t have a brother to tell me what was cool,” he says. “So I was the kid who watched Eddie Vedder dive from the balcony in the ‘Evenflow’ video. I watched [Nirvana’s] Krist Novoselic throw his bass guitar up into the air during the MTV Video Music Awards and pass out when the guitar smashed him in the face. I’d see that stuff, and I consumed it. I just thought that’s what you did if you were in a band.”

Tethered to a keyboard, Korin, the other half of The Hard Lessons, moved less. But when she took her turn singing lead, her shouty, bluesy ballads landed just as many punches. It was a counterpoint — well-planned change of pace in sets designed to build, pull back, and then take everyone over the top together. “I mean, I was in middle school band. I played the French horn. Then the thrill was playing ‘Hot Cross Buns’ and sounding good together. But I’ll tell you what the whole thing meant to me. When we’d have 1,000 people show up, 100 of them would be my friends and family; to me, that meant there were 900 people that were there just to hear my band. That’s when I felt like I was becoming a professional musician.”

The success came quickly in part because they were good people. Augie was an earnest “fanboy” of his Detroit garage rock idols, and he and Korin spent the better part of three years, four nights a week, going to shows before they even had a band. “When we started out, getting gigs was easy,” he says. “The bands would be like, ‘you know that guy Augie who jumps on stage with us and buys all the records and makes homemade T-shirts — that guy’s got a band now.’ So they’d let us open because they knew we loved the music.” Their pipe dream of “one day playing the Lager House” was realized within a couple months. At that time, the years ahead of headlining sold-out shows at storied Detroit venues like the Magic Stick and St. Andrews Hall would have sounded laughable.

But even then, the music wasn’t always enough to pay the bills. Like many working musicians, they both had lengthy resumes of other jobs. Augie’s included painting bathrooms at a bar and pouring cement during the construction of The Loving Touch, a club owned by their manager. For Korin, it was sometimes waitressing, sometimes bartending, but more often substitute teaching. It was a flexible, ad hoc gig that helped earn the couple a regular paycheck between weekends on the road. Augie and the tour van even became Friday after-school regulars — jockeying with the parents curbside so he could pick Korin up for tours where they could hit Toledo, Cleveland, and New York and still be back to normal life by Tuesday.

But for Korin, being a teacher — even an occasional one — allowed her to flirt with a calling that had been the passion of her college years. She was good at it, too, and the intermittent one-day classroom gigs eventually turned into longer-term opportunities. In 2010, she got an offer for a full-time position at the school where she was a regular sub. Having just gotten off an exhausting year-long tour, it felt like a chance to catch their breath, write the new album — a chance, for the first time since college, to have health insurance. Given the latter, they even started weighing whether the time was right to start a family — something they’d wanted since they were 19-year-old sweethearts, before they even had a band.

When Korin accepted the job, it didn’t really feel like a big change of life trajectory. But it got complicated a few weeks later when they got a call from their record label: They Might Be Giants, the quirky veteran darlings of the indie-rock world, had heard their new album and wanted The Hard Lessons to open on an upcoming national tour. It would mean two straight months on the road playing to thousands, not hundreds — and doing so at legendary venues like the Fillmore East and Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. The opportunity was, as Augie remembers, “everything you work for.”

Korin says as soon as she heard the news, she started looking for ways to reconcile the tour calendar with the number of days off allowed in her teaching contract. “But no matter how you looked at it, there was always a giant comma at the end of the sentence,” she says, “followed by, ‘but I just don’t see how it’s going to work.’”

Over the next few weeks, there were dozens of conversations, some of which ended in tears, most of which circled back to the same revelation: The teaching gig that had a few weeks back seemed like the perfect enabler for their careers as musicians was now looking like one half of an either-or dilemma. It also exposed a new truth — that Korin actually wanted to be a teacher, maybe more than she previously knew. And while the tour could be the closest thing they’d have to a big break, this might be hers. Eventually, they made a decision. After Labor Day, Korin would be preparing lesson plans for students rather than setlists for a national tour.

“Knowing where her heart was, and knowing my role as a husband, and knowing my own hopes and dreams for starting a family, I couldn’t say ‘no, quit that job, we’re doing this,’” Augie says. “I mean, I wanted to do the tour. I would love to tell my kids that I played the stage Hank Williams played. But you gotta have kids to be able to tell them that story.”

The family didn’t come right away, nor did the end of the band. They released another album even after Santino arrived; and before, there were plenty of photos of a pregnant Korin, holding down bass lines at weekend gigs at which she’d now sometimes recognize — and then quickly avert eye contact with — her students. The Dec. 26, 2011 show at St. Andrews Hall, where 600 fans welcomed them to the stage after their son’s birth, was particularly bittersweet. “I think the anticipation was ‘they’re back, the tours are gonna be back, there will be more records,’” Augie says. “And it ended up sort of being our coming out as a local band again. We definitely didn’t see it this way at the time, but it was sort of the beginning of the end.”

The family didn’t come right away, nor did the end of the band. They released another album even after Santino arrived; and before, there were plenty of photos of a pregnant Korin, holding down bass lines at weekend gigs at which she’d now sometimes recognize — and then quickly avert eye contact with — her students. The Dec. 26, 2011 show at St. Andrews Hall, where 600 fans welcomed them to the stage after their son’s birth, was particularly bittersweet. “I think the anticipation was ‘they’re back, the tours are gonna be back, there will be more records,’” Augie says. “And it ended up sort of being our coming out as a local band again. We definitely didn’t see it this way at the time, but it was sort of the beginning of the end.”

Korin says the arrival of their second son, Orlando, marked the closest thing to an official retirement — a plot point supported by their Tumblr posts abruptly ending with a birth announcement from two years ago. But the off-ramp to one dream opened up a wider path to another. Korin’s teaching career took off, first with that job at the renowned International Academy in Bloomfield Hills, and later, at a Catholic school run by progressive, free-thinking nuns. The steady income also allowed them to buy a house in Rochester, where the rhythm of weekend family bike rides in the suburbs replaced the Friday and Saturday gigs.

But the transition to normal life was trickier for Augie. “Korin had friends and interests outside the music scene — I didn’t. I mean, after a better part of a decade of doing this — and people refer to you as ‘Augie Hard Lessons’ and not your last name — that becomes a big part of your identity. When that goes away, you have to ask yourself who you are.”

At first, he split time between playing gigs with friends who had bands and teaching music lessons to the next generation of Detroit musicians at the nearby School of Rock. He also threw himself into the “vocation” of fatherhood, which he says he approached with the cliché work ethic of a first-generation American. Augie, like Korin, also had a teaching degree he’d been sitting on. And when he became a familiar enough face around her school, and word got around, the sisters put his eclectic experience to use as director of a new after-school activities program. After a decade of working elbow-to-elbow, they’d again at least be back working for the same team. Today, their school’s age-zero-and-up curriculum even means the whole family spends weekdays under one roof.

Once the kids are in bed for the night, we meander through more stories of the old days and eventually to the obvious, but necessary, questions about regrets and what-ifs.

“I can imagine what that tour would have felt like, smelled like — rocked like,” Korin says. “But in life, there’s always a giant comma. And now my giant comma is having my 6-year-old son Santino and 2-year-old Orlando. It’s my home. My family. And not just our own family. There were seven years of our lives where we basically missed every wedding, every birthday, every baby shower.”

For Augie, the feelings are similar, though still a little complicated. He admits that he’s not sure if he’s completely over them turning down the tour, and he and Korin then laugh comfortably about a subject that could have easily opened up a rift in their marriage, but which now, long resolved, instead stands as a big fat ‘I love you.’

I then ask Korin — with the preface that men sacrificing for their families need not be glorified just because it’s more unusual — if she feels like he did it for her.

“Yes,” she says, immediately, then pausing, choking on the emotion of an answer, which surprises him and maybe her a little too. Then she turns her head. She’s talking directly to him now. “You gave up everything.”

“But I’ve also gained everything,” he answers back to her. And then they start talking and laughing amongst themselves about how good Santino’s poems are. How their music memorabilia has been displaced by Orlando’s baby shoes and other artifacts from their new life. How Santino has perfect pitch, then as evidence, out from the pocket comes the phone and the video of the 6-year-old singing The Stooges’ “No Fun.” The kid’s got Iggy’s punchy phrasing down.

Eventually, the subject of a reunion show comes up, followed by a theoretical headcount of the potential turnout. “The two couples who got engaged at our shows — we had to mean something to them,” Augie says, wryly. “Plus, your parents and my parents,” Korin adds.

When you need them, you can always bet on family.

|

|

|