According to Julian Liebman — you may know him better by his radio alias, Specs Howard, which is also the name on his Southfield building — when he opened his broadcasting school in 1970, there were at least five competing schools in metro Detroit. And it wasn’t a competition he necessarily wanted to enter.

“The worst thing in the world to me was a broadcast school,” he says today, sitting in the lobby of his Specs Howard School of Media Arts. That’s because, overall, Howard explains, broadcast schools had terrible reputations.

“A disc jockey was out of work and would think, ‘Hey, I can pick up a few bucks and charge students to become announcers,’” he says. “They would practice ‘A-E-I-O-U,’ he’d hand them a script to read with cues like, ‘Don’t read too fast. Don’t mispronounce words,’ say, ‘Hey, you’re great,’ and take their money. There was no job search or anything.”

Eventually, Howard became an out-of-work disc jockey himself. The Martin and Howard morning show he co-hosted with the late Harry Martin dominated the Cleveland market for years, but Detroit’s WXYZ-AM stole the duo away at what turned out to be the worst possible time: 1967. Not only was their arrival totally overlooked amid that summer’s riots and newspaper strike, but the station changed its format from Top 40 to adult pop after they began. In short order, they were replaced by a whippersnapper named Dick Purtan, who went on to become Detroit’s king of comedy and a National Radio Hall of Fame inductee.

“I had been on the air all my life, and I had to find a job,” Howard says. “I had four little kids, and Ceil [his wife of 66 years, Celia] said we had to feed them. I looked around, but nothing appealed to me. Then somebody mentioned [longtime Detroit rock ’n’ roll DJ] Lee Alan had this little storefront school that was licensed by the state, but he was moving into advertising, so I went to talk to him.

“I had no money, but I found a couple of people who did, and we bought it. That’s how we started.”

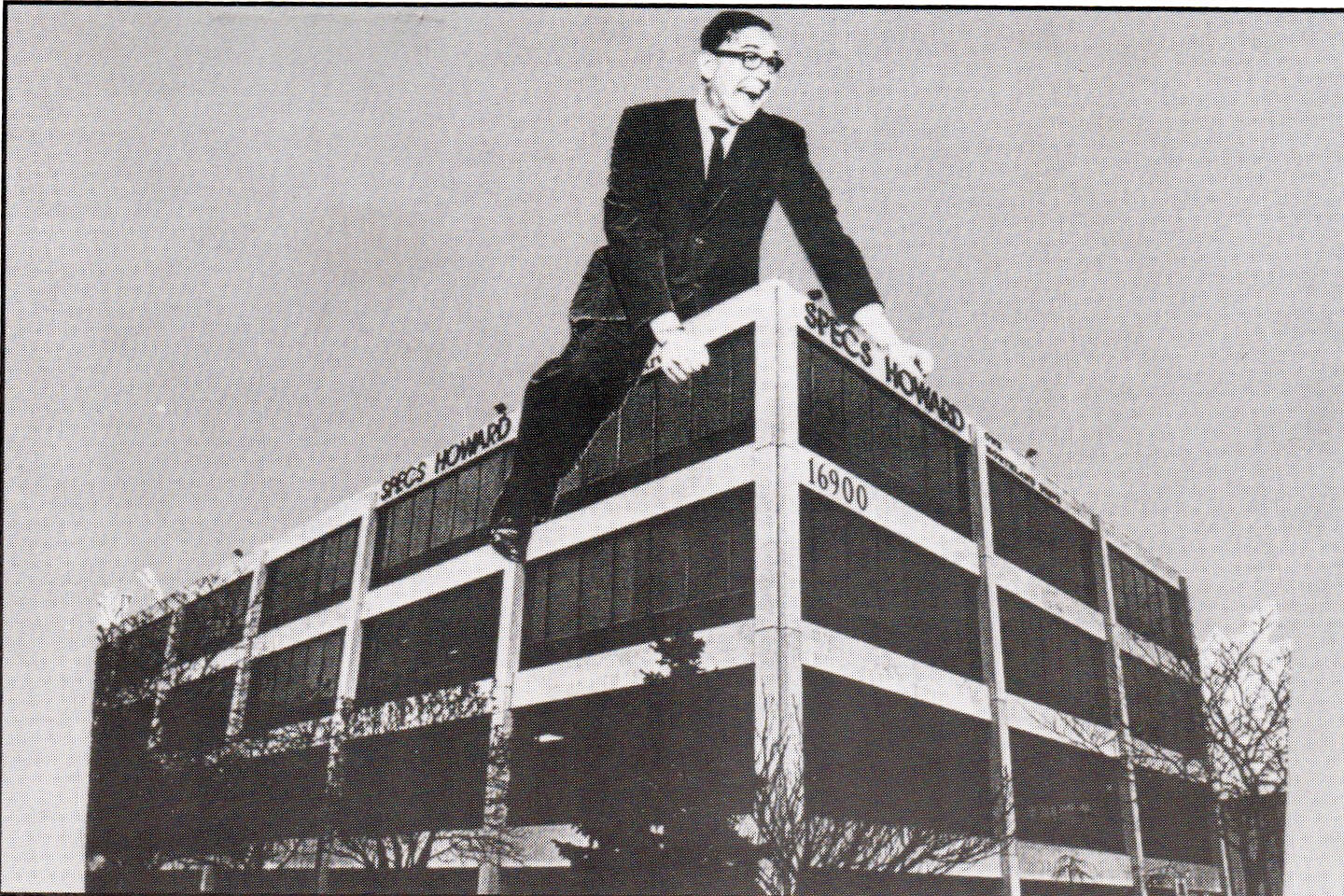

As you’d expect from a guy called Specs, he went into the new endeavor with a clear vision. “The big thing was, we were going to teach the basics,” he says. The result of that vision is now a sight to behold.

The school marked its 50th anniversary on Jan. 14 and plans to tentatively celebrate its golden milestone in April with an event that includes the induction of 50 alumni — one for each year of the school’s existence — into its Specs Howard Hall of Fame.

School president Martin Liebman — Specs and Celia’s eldest son and the man who runs day-to-day operations — estimates more than 16,000 graduates have passed through its doors. Many have risen to prominent broadcasting and media positions in Detroit and beyond. The late country Radio Hall of Fame personality Joe Wade Formicola and Detroit album-rock radio legend John O’Leary were among the early graduates, and this year’s Hall of Fame class includes such noted on-air talents as FOX 2’s Charlie Langton and Amy Andrews, WWJ-AM’s Oneil Stevens, former WDET-FM talk-show host Craig Fahle, punk-rock pioneer Mike Halloran, and video wizard Tony D’Annunzio, producer and director of the Emmy-winning documentary Louder Than Love: The Grande Ballroom Story.

“I got into it for radio,” D’Annunzio recalls. “I didn’t even know about TV, or that there could be a profession there. In the ’80s, cable was just beginning. So, the school started a path for me — the doors and opportunities, they opened up.

“In fact, I met my wife while working on a Black Crowes video at Pine Knob [now DTE Energy Music Theatre]. If I hadn’t gone to Specs, I wouldn’t have met my wife, wouldn’t have had kids, wouldn’t have made a film, wouldn’t be talking to you. It was life-changing.”

Recognizing the rise of media conglomerates and satellite radio and their potential impact on the broadcasting job market, the school started to evolve. Howard expanded its offerings to include a graphic design program in 2008, changed the school’s name from Broadcast Arts to Media Arts in 2009, and introduced the digital media arts program, which offers web design and video editing training, in 2010.

Still, the most fascinating element of the Specs Howard story is Howard himself.

Now using a wheelchair due to an accident that fractured his left leg, Howard has overcome far greater challenges — childhood polio, its consequent physical maladies, and anti-Semitism, to name a few — to build a legacy that led to a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Michigan Association of Broadcasters 11 years ago. At 93, he’s as sharp and charismatic as ever and still goes to his namesake institution weekly.

“It’s humbling, it is,” Howard says, reflecting on his legacy from the school’s temporary location on Lahser Road. Its longtime facility on Nine Mile was severely damaged by fire and flood last year. “And it’s a little frightening, because most of us look forward, but looking back can be hard. I always wonder if [the graduates] would have gotten jobs anyway if they hadn’t come here. A lot of them had good voices and personalities. But we taught them the fundamentals to help them start their careers.”

That look back can be sobering. “I was a one-man band in the beginning,” he recalls. “I interviewed prospective students, answered the phones in the morning, and taught at night. My first class had six students. All of them got jobs, but five of them never paid me a dime. The sixth one said, ‘I’m going to pay you,’ but I got a couple of nickels from him. I was so disappointed. I learned to get payment up front.”

Howard ultimately made enough to advertise on stations such as WRIF-FM, where a young program director named Dick Kernen had wearied of trying to herd a bunch of rock-radio cats. Kernen became one of Howard’s first hires, as teacher and eventually vice president of industry relations, extolling the virtues of Specs Howard students to small- and medium-market station execs while securing entry-level positions for graduates. Now 82, Kernen is one of the most beloved figures in broadcasting and still works at the school.

“What else would I do?” Kernen reasons. “I’m still here because of Specs Howard. He has more integrity than any man I’ve ever met.”

This year’s Hall of Fame inductees include Alisa Zee, the former WWJ-AM traffic reporter who is the host of a weekly public affairs program for five Detroit radio stations, national morning-drive newscaster for iHeartRadio — and Howard’s daughter. “This is such an honor, in so many ways,” says Zee, who, like all inductees, was elected through online voting.

“There have been many things that I’ve not been awarded because of the fear people would think, ‘Oh, they only gave that to her because she’s Specs Howard’s daughter.’ And that’s my life. I am proud of my father, and I am honored that every day I get to open a mike and carry on his legacy.”

Zee is busy perpetuating that legacy. She has been working for years on a documentary about her father and is trying to raise $75,000 for production costs. “I have the people who are going to shoot it for me,” she says, “but they’re going to come out first and shoot some footage on spec.”

She stops a moment, realizing her unintended humor. “Yes, we’re shooting Specs on spec, right?”

|

|

|